The digital platform economy has impacted employment in many ways. “Traditional” jobs, such as office workers and the service industry, are being enhanced by collaboration, video, and cloud-based platforms. New tech industry jobs are being created in countries that have successfully encouraged the development of platform companies. Finally, many platforms foster the sharing and gig economies and have created employment opportunities for individuals who have an asset, skill, or time to share. In this Signal post, we touch briefly on employment in the tech industry but focus primarily on employment in gig and sharing platforms and provide an update on how the early promises of the sharing and gig economies have played out in reality.

The promise of platforms

Digital platforms are disrupting established business practices and redefining the relationships between producer, consumer, and worker. By creating multi-sided marketplaces and ecosystems, they promise to democratise both consumption and production. Empowering participants and creating environments where workers have flexibility and control over the goods, services, and labour they provide are some of the key goals of platforms.

The growth of the platform economy is part of what the World Economic Forum describes as the 4th Industrial Revolution (4th IR). While the 4th IR includes technological advances in areas like robotics and artificial intelligence, it also includes eCommerce, mobile payments, as well as sharing and marketplace platforms. As these technologies spread globally they bring opportunities for people in developed as well as developing countries. Whether you’re in Spain or sub Saharan Africa, if you have an asset to share, a skill, or a product you produce, the platform economy gives you the opportunity to monetise it.

Policies to encourage growth

While the users of platforms are increasingly global, the development of the platforms, and the tech industry jobs are concentrated in a small number of countries, mainly in the US and China. Other countries, such as Finland, Canada, and the EU as a whole, are actively working to encourage the creation and growth of locally developed platforms. As we wrote in an earlier Signal post about GDP and the Platform Economy, countries recognise the need to encourage the development of platforms to ensure future growth in their economy and employment for their citizens.

In addition to fostering the local tech industry, many countries recognise that some platforms will replace “traditional” jobs. For example, Finnish researchers estimate that 23% of jobs in Helsinki, such as salespeople, waiters, and accountants could be replaced by 2030 through digitalisation technologies such as robotics and Artificial Intelligence. Re-training displaced workers, through government programs or platforms such as Udemy or Google Career Certificates, are part of the solution to increasing employment opportunities.

Other policy initiatives are focused on equity and inclusion of women and minorities in the platform economy, as both tech workers and/or participants in the sharing/gig economy. The International Finance Corporation (IFC) and the European Commission (EC) created Digital2Equal, an initiative involving 17 leading technology companies with a focus on increasing opportunities for women in emerging markets.

The challenges created by the gig and sharing economy

While platforms have technically delivered on their promise of democratising production and consumption, they have introduced new challenges. Some platforms allow producers and “workers” more control over how their work is valued, while others are highly competitive and drive earnings lower.

Producers such as those selling products on Etsy, providing skilled services on Upwork, or renting properties on AirBnB face competition but generally have control over the prices they charge and how they operate. Producers/workers operating on platforms that provide ridesharing, food delivery, or crowdwork participate in a highly competitive environment with little control over the fees they’re paid and none of the benefits associated with being a “traditional employee”.

These challenges have been written about in detail recently, including: being at the mercy of bad reviews, high levels of pressure, working long hours, no employment benefits, low-paying crowdwork, concentrating economic gains in the hands of the platform, and poor working conditions inside eCommerce warehouses.

Creating a fair and sustainable gig and sharing economy

While labour laws and social security infrastructure vary by country, addressing the challenges associated with employment in the platform economy is a key issue for policymakers. The European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (EUROFound) outlined policy suggestions that include: clarifying employment status definitions for platform workers, setting minimum payment standards, setting up dispute-resolution mechanisms, and allowing platform workers to organise and establish representation.

The unique situation in the Nordic countries is highlighted by TemaNord (funded by the Nordic Council of Ministers). While platform work is still relatively small in Nordic countries, some platforms are being assimilated into the Nordic labour model, such as Foodora in Norway and Hilfr in Denmark reaching collective agreements with workers. However, other platforms are eroding the Nordic model, such as Uber instigating the deregulation of the taxi industry.

The World Economic Forum suggests four steps to build a fairer gig economy: rate platforms on fair work practices, ensure platforms are accountable to existing (or new) regulations, allow workers to organise, and allowing democratic ownership and worker cooperatives.

While Uber is advocating for the creation of a new employment classification for gig workers, some observers take the position that new policies and laws may not be required since they feel existing labour law and social security frameworks already apply to platforms and platform workers in most countries. They assert that a case-by-case assessment of different platforms will clearly identify if the workers are entrepreneurs or employees and which existing laws apply.

Selected articles and websites

The sharing economy has made life easier — and better too

Can work still have real meaning in the age of digital platforms?

WEF – How to build a fairer gig economy in 4 steps

UN Frontier Technology Quarterly – Does the sharing economy share or concentrate?

EuroFound – Employment and working conditions of selected types of platform work

Past Signals related to this one

Finland’s master plan for platform economy

Additional references

The Fourth Industrial Revolution (WEF)

Does the fourth industrial revolution offer hope for workers in the developing world

Finland’s master plan for platform economy

Canada Innovation Supercluster Initiative

Digital2Equal – Case studies on women and the platform economy

Work revolution and digitalisation – what changes are promised for the labour market in the Helsinki metropolitan area? (Työn murros ja digitalisaatio – mitä muutoksia on luvassa pääkaupunkiseudun työmarkkinoille?)

How modern workers are at the mercy of ratings

Survey reveals app drivers’ misery

California judge rules Uber and Lyft must classify drivers as employees

A Data-driven analysis of workers’ earnings on Amazon Mechanical Turk

Here’s what it’s like to work in an Amazon warehouse right now

TemaNord – Platform work in the Nordic models: Issues, cases and responses

Uber CEO advocates for ‘third way’ to classify gig workers while fighting California labour lawsuit

Markus Äimälä: Platform economics and labor law – a lot of noise from nothing? (Markus Äimälä: Alustatalous ja työoikeus – paljon meteliä tyhjästä?)

Rantahalvari: The platform economy challenges social security – perhaps not (Rantahalvari: Alustatalous haastaa sosiaaliturvan – ehkei kuitenkaan)

PWC Legal – Gig economy employment status

Commons, zebras and team economy

The platform economy is much more than business giants Uber, Amazon or Google. Platforms can facilitate a transformation in ways of organising work, value creation, sharing, and resources. While the currently dominant development direction tends to favour large platform companies with monopoly statuses, alternative undercurrents can be identified.

Why is this important?

The focus in the platform economy has largely been on how it enables new ways to create value. Value comes from both users and producers while the platform adds its value to the ecosystem by providing tools for matching and curating the content. Network effects further multiply the value based on the extensiveness of the network.

The sole focus on value creation has, however, lead to ignoring the mechanisms by which value is distributed in the network. Platforms both mediate value creation and add value through connecting actors, sharing resources, and integrating systems, but the question is, how is this value shared? Especially platforms with near monopoly status tend to aggregate much of the value to the platform itself and not share it back to the users of the platforms in a fair amount. Platform companies, like other companies, give the surplus to their shareholders. In some cases, it could even be said that platforms exploit their users by treating them as workforce without benefits or as sources of data to be sold to advertisers. At the same time, little attention is put into how platforms serve society. The discussion is more about how they disrupt existing industries and navigate in the gray areas of legislation.

Three approaches challenging the dominant platform business

Although the big platform companies produce most of the headlines, there are interesting initiatives for alternative forms of platform economy. One is the revitalisation of the idea of commons. In the context of platforms and peer-to-peer economy, commons is understood as a mode of societal organisation, along with market and the state, and combines a resource with a community and a set of protocols. A key question related to platform economy is what data, tools or infrastructure should be treated as commons, how to govern them and how to build both for-profit and non-profit services on top of them. These and other questions of a “commons economy” are being experimented with in peer-to-peer initiatives, platform cooperatives, and blockchain-based distributed autonomous organizations.

In the same way that commons challenges the notion of ownership, a growing number of companies called “Zebras” are challenging the notion of growth. “Zebras” are companies that aim for a sustainable prosperity instead of maximal growth like “Unicorns”. They can still be for-profit but also do social good. An interesting question is whether platform economy can be used to transform the current growth-based economic system towards a more sustainable version, or will the “Zebras” as well as cooperatives and commons be left to the margins in the dominance of platform monopolies.

A third interesting idea utilising the new possibilities of connecting and collaborating through digital platforms is the idea of team economy by GoCo. It challenges the idea of a permanent organisation. In team economy, groups form around an issue or a problem and disperse once the work is done. In contrast to gig economy, the tasks aren’t simplified or clearly defined, but rather what needs to be done is jointly explored with the customer. A platform is needed to connect and offer a collaborative workplace but also provides a record of everything a person has done, a sort of online CV for the platform age.

It remains to be seen to what extent commons, “zebras” and team economy can influence the development of platform economy, but they are interesting ideas to keep an eye on.

Selected articles and websites

- ETUI Policy Brief: The emergence of peer production

- Transnational Institute: Commons Transition and P2P

- Hinesight: Commons or commodities?

- Medium: Zebras Fix What Unicorns Break

- GoCo

Demographic factors in the platform economy: Gender

Often it may feel like we are all anonymous and equal in the online world, but at other times age, gender and other demographic and socio-economic factors seem to matter greatly. In this signal post, we discuss gender in the context of the platform economy. (See also previous post focussing on age.) What is the gender balance among platform users? Who designs and programs platforms? And what is the role of user behaviour and online culture?

Why is this important?

Platform economy has potential to support societal integrity by providing an abundance of opportunities to women and men alike. For example, gig work enabled by digital platforms brings flexibility regarding working hours and location, which is assumed to benefit stay-at home parents, who under other circumstances would stay outside the workforce.

Zooming into platform user populations, in social media usage, Uber passengers and consumers of the on-demand economy there has been found little or no difference in the US in the numbers of women and men. Sounds good! However, if we look at Uber drivers, as much as 86% are male. The exact opposite situation is found with a marketplace for handmade and vintage goods Etsy, where out of the 1.5 million sellers 86% are female. Could it be that platforms reflect and replicate the existing biases and traditions when it comes to the division of labour between women and men?

Another central point of interest is for whom platforms are designed. And who designs them? The inherent male-dominance in the software industry and venture capital is reflected in platforms in that it is dominantly men who design and make decisions about how platforms function. A characteristic example of challenges in this area is the recent controversy over a Google employee manifesto, which shows that despite efforts to increase diversity, old attitudes are very much alive.

An equally important question is how people behave and treat one another when using platforms. A case in point is the numerous incidents of online harassment and doxing (e.g. maliciously gathering and releasing private information about a person). One alarming example from video game culture gone astray is the Gamergate controversy. Online culture also shows in reputation and rating systems, where disclosing of background information such as gender may influence behaviour unfairly.

Things to keep an eye on

For new as well as existing platforms, the topic of gender is an important aspect of consideration in platform design. User strategies can at best pinpoint specific gender-related needs and provide targeted and tailored solutions. Platform owners should also acknowledge the responsibility and equality points of view to ensure the platform welcomes all unique users and treats them on an equal footing. Underlying algorithms as well as the culture of the user population should support equal opportunities and broadmindedness.

Also, it will be increasingly important for governments to keep gender equality in view when promoting digitalisation agendas, especially to involve women. Nations do face different types of challenges based on cultural context and nuances as well as status in financial and technological development, and some recommendations on how to harness women’s potential are given in a recent study.

Selected articles and websites

Harvard Business Review: The On-Demand Economy Is Growing, and Not Just for the Young and Wealthy

Pipes to platforms: How Digital Platforms Increase Inequality

GlobalWebIndex: The Demographics of Uber’s US Users

Uber: The Driver Roadmap

Pew Research Center: Social Media Fact Sheet

Pew Research Center: Online Harassment 2017

Poutanen & Kovalainen (2017): New Economy, Platform Economy and Gender

CNNtech: Storm at Google over engineer’s anti-diversity manifesto

Watanabe et al. (2017): ICT-driven disruptive innovation nurtures un-captured GDP – Harnessing women’s potential as untapped resources

Wikipedia: Gamergate controversy

European Parliament, Think Tank: The Situation of Workers in the Collaborative Economy

openDemocracy: Back to the future: women’s work and the gig economy

Demographic factors in the platform economy: Age

Intuitively thinking online platforms seem to be all about empowerment, hands-on innovation and equal opportunities. In the digital world, anyone can become an entrepreneur, transform ideas into business and, on the other hand, benefit from innovations, products and services provided by others. But how accessible is the platform economy for people of different age? And how evenly are the opportunities and created value distributed? Some fear that platforms are only for the young and enabling the rich get richer while the poor get poorer.

In this signal post, we discuss age in the context of the platform economy. In future postings, we will explore other factors such as gender and educational background.

Why is this important?

When it comes to ICT (Information and Communication Technology) skills and adoption, the young typically are forerunners. For example, social media platforms were in the beginning almost exclusively populated by young adults. But studies show that older generations do follow, and at the moment there is little difference in the percentage of adults in their twenties or thirties using social media in the US. And those in their fifties are not too far behind either!

Along with the megatrend of aging, it makes sense that not only the young but also the middle-aged and above are taking an active part in the platform economy. Some platform companies already acknowledge this, and tailored offering and campaigns to attract older generations have been launched for example in the US. In Australia, the growing number of baby boomers and pre-retirees in the sharing economy platforms, such as online marketplaces and ride-sourcing, has been notable. Explanatory factors include the fact that regulation and transparency around platform business have matured and sense of trust has been boosted.

One peculiar thing to be taken into account is that many platforms actually benefit from attracting diverse user segments, also in terms of age. This shows especially in peer-to-peer sharing platforms. The user population of a platform is typically heavy with millennials, who are less likely to own expensive assets such as cars or real estate. Instead, their values and financial situations favour access to ownership. But the peer-to-peer economy cannot function with only demand, so also supply is needed. It is often the older population that owns the sought-after assets, and they are growingly willing to join sharing platforms. Fascinating statistics are available, for example, of Uber. As much as 65% of Uber users are aged under 35, and less than 10% have passed their 45th birthday. The demographics of Uber drivers tell a different story: adults in their thirties cover no more than 30%, and those aged 40 or more represent half of all drivers. In a nutshell, this means that the older generation provides the service and their offspring uses it.

Things to keep an eye on

In the future, we expect to see more statistics and analysis on user and producer populations of different types of platforms. These will show what demographic segments are attracted by which applications of the platform economy as well as which age groups are possibly missing. The information will help platforms to improve and develop but also address distortion, hindrances and barriers.

It may also be of interest to the public sector to design stronger measures in support of promoting productive and fair participation in the platform economy for people of all ages. Clear and straightforward regulation and other frameworks will be important to build trust and establish common rules.

Selected articles and websites

GlobalWebIndex: The Demographics of Uber’s US Users

Growthology: Millennials and the Platform Economy

Harvard Business Review: The On-Demand Economy Is Growing, and Not Just for the Young and Wealthy

INTHEBLACK: The surprising demographic capitalising on the sharing economy

Pew Research Center: Social Media Fact Sheet

Pipes to platforms: How Digital Platforms Increase Inequality

Uber: The Driver Roadmap

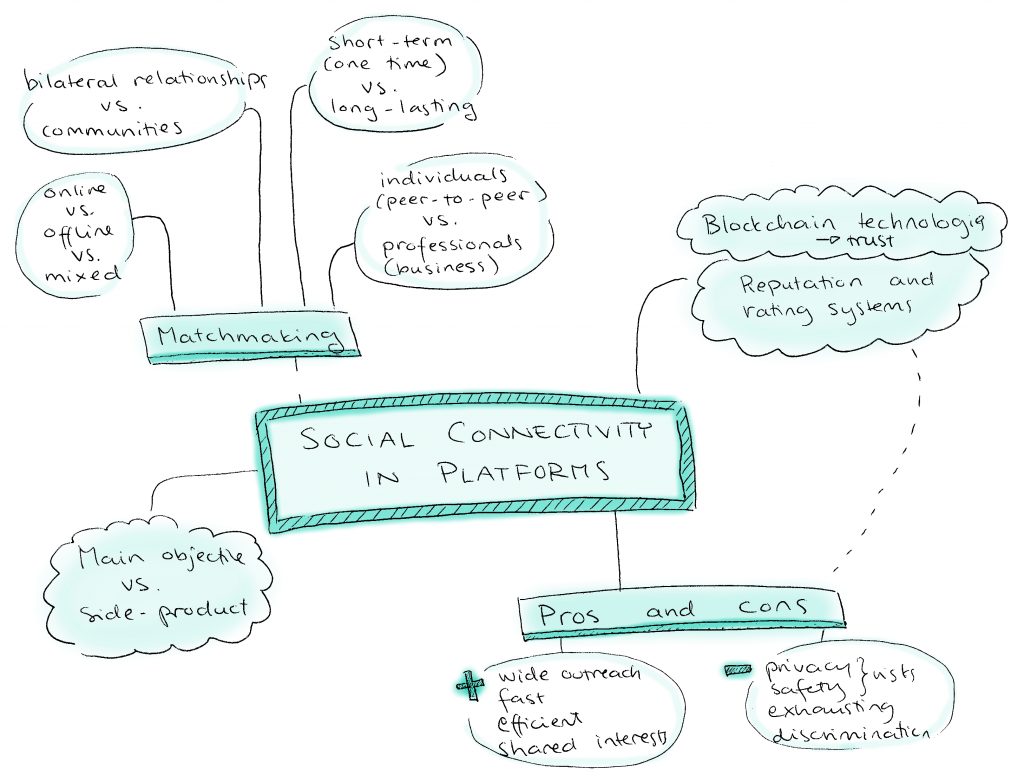

Social connectivity in platforms

Platforms are all about enabling connections to form between actors, typically producers and users of any given tangible or intangible commodity. But to what extent do these connections result in social value for individuals? There are of course social media platforms that by definition focus on maintaining or creating human relationships whether based on family ties, existing friendships, professional networking, dating or shared hobbies or interests. Interaction, communication and social ties nevertheless take place in other platforms too, and the positive and negative impacts of these may come as a rather unexpected side effect to the platform owner as well as users.

For example, ride-sourcing and hospitality platforms are virtual matchmakers, whose work comes to fruition when the virtual connection proceeds to a face-to-face meeting. A ride is then being shared with or a home is being rented to someone who only a little while back was a stranger. Many suchlike relationships remain one-time transactions, but they can also grow to regular exchanges over the platform or profound relationships outside the platform. Connectivity is as much a part of peer-to-peer platforms as professional and work-related platforms. You may form a personal connection with a specific IT specialist over the IT support system platform even if you never met them offline. Or supply chain business partnerships may evolve out of a one-time task brokerage platform transaction.

Why is this important?

The benefits of platform economy regarding social connectivity are the wide outreach and extremely fast and efficient matchmaking based on personal, professional of other mutual interests. In spite of complex technologies and big data flows, these social connections on platforms can be truly personalised, intimate and rewarding. The flipside of the coin is risks around privacy, safety and security. Reputation, review and rating systems are important ways to tackle these and could help to strengthen the sense of trust and community across user populations of platforms. In fact, one interesting finding of social connectivity in platforms is that relationships are maintained and formed bilaterally between the individual as well as among groups, communities and actor ecosystems. Short-term or long-lasting, these relationships often mix online and offline realities.

Additional concerns related to social connectivity in platforms is how much they eventually promote equality and fairness or if the social interaction is more of a burden than a benefit. Reputation and rating systems may result in unfair outcomes, and it may be difficult for entrants to join in a well-established platform community. Prejudices and discrimination exist in online platforms too, and a platform may be prone to conflict if it attracts a very mixed user population. In the ideal case, this works well, e.g. those affluent enough to attain property and purchase expensive vehicles are matched with those needing temporary housing or a ride. But in a more alarming case, a task-brokerage platform may become partial to assigning jobs based on criteria irrelevant to performance, e.g. based on socio-economic background. Platforms can additionally have a stressful impact on individuals if relationships formed are but an exhaustingly numberous short-term consumable.

Emerging technologies linked to platforms are expected to bring a new flavour to social aspects of the online world. The hype around blockchain, for example, holds potential to enhance and ease social connectivity when transactions become more traceable, fair and trustworthy. It has even been claimed that blockchain may be the game changer regarding a social trend to prioritise transparency over anonymity. Blockchain could contribute to individuals and organisations as users becoming increasingly accountable and responsible for any actions they take.

Things to keep an eye on

Besides technology developers and service designers’ efforts to create socially rewarding yet safe platforms, a lot also happens in the public sector. For example, European data protection regulation is being introduced, and the EU policy-making anticipates actions for governance institutions to mobilise in response to the emergence of blockchain technology.

An interesting initiative is also the Chinese authorities’ plan for a centralised, governmental social credit system that would gather data collected from individuals to calculate a credit score that could use in any context such as loans applications or school admissions. By contrast, the US has laws that are specifically aimed to prevent such a system, although similar small-scale endeavours by private companies do to some extent already exist.

Selected articles and websites

Investopedia: What Is a Social Credit Score and How Can it Be Used?

General Data Protection Regulation (EU) 2016/679 – EUR-Lex

European Parliament: What if blockchain changed social values?

European Parliament: How blockchain technology could change our lives

Rahaf Harfoush: Tribes, Flocks, and Single Servings — The Evolution of Digital Behavior

Koen Frenken, Juliet Schor (2017): Putting the sharing economy into perspective, Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions

Paolo Parigi, Bogdan State (2014): Disenchanting the World: The Impact of Technology on Relationships

Social impacts of the platform economy

Platforms create value well beyond economic profits, and the topic of social and societal impacts resulting from the emerging platform economy has been getting more and more attention lately. Platform economy undoubtedly has both positive and negative impacts on individuals and families as well as wider communities and entire societies. However, the range and depth of these impacts can only be speculated, as only very early evidence and research on the topic has been produced. After all, the platform economy is only in its infancy.

Why is this important?

Platforms have potential to address major societal challenges such as those connected to health, transport, demographics, resource efficiency and security. They could massively improve our individual daily lives as well as contribute to equal opportunities and progress in developing economies. On the other hand, platform economy can result in negative impacts in the form of disruptions and new threats. Privacy and safety concerns have deservedly been acknowledged, and other possible risks include those related to social exclusion, discrimination and the ability of policies and regulations to manage with whatever platform economy may bring about.

Some examples of positive and negative social impact categories of the platform economy include the following, which may distribute equally, create further division or bridge the gap among various social segments:

- employment and unemployment

- livelihood and wealth

- education and training

- skills, knowledge and competences

- health and physical wellbeing

- mental health and wellbeing

- privacy, safety and security

- social inclusion or exclusion, access to services, etc.

- new social ties and networks, social mixing

- social interaction and communication: families, communities, etc.

- behaviour and daily routines

- living, accommodation and habitat

- personal identity and empowerment

- equality, equity and equal opportunities or discrimination

- citizen participation, democracy

- sufficiency or lack of political and regulatory frameworks.

Platforms may have very different impacts on different social groups, for example, based on age, gender, religion, ethnicity and nationality. Socioeconomic status, i.e. income, education and occupation, may also play an important role in determining what the impacts are, although it is also possible that platform economy balances out the significance of suchlike factors. One important aspect requiring special attention is how to make sure that vulnerable groups, such as the elderly or those with disabilities or suffering from poverty, can be included to benefit from the platform economy.

Things to keep an eye on

Value captured and created by platforms is at the core of our Platform Value Now (PVN) project, and there are several other on-going research strands addressing social and societal impacts of the platform economy. One key topic will be to analyse and assess impacts of the already established platform companies and initiatives, which necessitates opening the data for research purposes. To better understand the impacts and how they may develop as platform economy matures is of upmost importance to support positive progress and to enable steering, governance and regulatory measures to prevent and mitigate negative impacts.

Selected articles and websites

Koen Frenken, Juliet Schor, Putting the sharing economy into perspective, Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, (2017)

The Rise of the Platform Economy

Uber and the economic impact of sharing economy platforms

VTT Blog: Openness is the key to the platform economy

SUSY project: Solidarity economy

Technophobia – fear of technology

Although new technology intrigues us and makes us curious about what can be achieved with it, the flipside of the human reaction to anything new is suspicion and even fear. Technophobia means fear of technology, and it can stem, for example, from not fully understanding how something works, possibility of danger and negative impacts or risk of malicious misuse. Another flavour of technophobia is anxiety over our personal competences to deal with new technologies and the downright possibility of social exclusion if we lack the access or skills to adopt them.

Why is this important?

Some of the technology fears connected to the platform economy have been around for a long time, and they apply to pretty much any technologies linked to machines and computing. The archetype of suchlike concerns is the fear of losing our jobs because of automation, something that has been a worry for well over a century.

Another major concern in the context of platform economy is how the disruption to economy will impact us as individuals (for example moving from regulated labour market to the gig economy), as businesses (for example smaller companies being bulldozed by large platform corporations) or as society (for example governments trying to keep up with regulation, legislation and fiscal needs related to platforms).

Fears do not either escape the indirect risks and negative impacts that may arise with platformisation, such as loss of knowledge and survival mechanisms if digitalised assets are destroyed or if there’s a prolonged power cut. Intentional misuse and criminal activity is also a scare experienced by many, and evolving platform configurations may indeed be extremely vulnerable.

Examples of specific fears include:

- Fear of technology eliminating jobs and the need for human workers.

- Fear of technology taking over the human (individual or society).

- Fears related to privacy and cyber security.

- Fear of losing control and getting lost in the technology mesh.

- Fear of not learning the skills or not having access to use a technology.

- Fear of dependence and not surviving without the technology (for example in case of a power cut).

- Fear of negative social and societal impacts (for example lack of face-to-face interaction).

- Fears related to fast and vast information flows (for example validity of news).

- Fear of governments not having the means to monitor and control malicious and criminal activity related to new technologies.

Things to keep an eye on

The important thing is to try understand the root causes of fear of technology in the context of platform economy, regardless of whether the threats are real or perceived. Also, it should we noted that technophobia may influence not only consumers but businesses and policy-makers alike. Through addressing technology-related concerns appropriately we can ensure that individuals as well as companies and other organisations have the courage to make the best of the platform economy opportunities. On the other hand, the assessment of fears helps us to pinpoint risks and vulnerabilities that need to be fixed in technological, regulatory or other terms. To dispel mistrust, impartial and validated information to support technology proficiency and awareness is needed. Similarly important are also investments in for example digital security and technology impact assessment.

Selected articles and websites

Robots have been about to take all the jobs for more than 200 years. Is it really different this time?

The Victorians had the same concerns about technology as we do

Fear of Technology

Hot Technology Pilots in 2016 – Fear & Chaos in Technology Adoption

Why do we both fear and love new technology?

Americans Are More Afraid of Robots Than Death. Technophobia, quantified

Ever-present threats from information technology: the Cyber-Paranoia and Fear Scale

The access – Platform economy: Creating a network of value

Choosing a Future in the Platform Economy: The Implications and Consequences of Digital Platforms

Reputation Economy

Why is this important?

Platform economy often requires trusting strangers. One mechanism for ensuring that everyone plays nicely is to have a reputation system in place. Customers rate the service provider (e.g. Uber driver or Airbnb apartment) and the service provider in turn rates the customer. The ratings or at least their averages are public, which influences who we trust and how we behave in the platform. Reputation is thus a valuable asset in the platform economy.

Things to keep an eye on

Because reputation is valuable, the mechanisms that affect how it is created, shared and used are important. Can the reputation scores be transferred to other services or used in a way not originally intended? Will reputation economy become a new surveillance and control system, as depicted in dystopian images of future, which do not seem so far off given the failed startup Peeple and the Sesame Credit system in place in China.

Selected articles and websites

The Reputation Economy: Are You Ready?

We’ve stopped trusting institutions and started trusting strangers

The reputation economy and its discontents

China has made obedience to the State a game

Black Mirror Is Inspired by a Real-Life Silicon Valley Disaster

Platform cooperatives

Why is this important?

The current big players in the platform economy operate with the aim to increase shareholder value. Although the business model is different than with most incumbents, the business logic is rather similar. However, platforms support also other forms of organisation and value distribution, for example the cooperative. What if the drivers would own the platform they use for connecting with customers? Herein lies potential impact to the way economic value is distributed.

Things to keep an eye on

Technology is not an obstacle for platform coops to scale, the hurdles lie in social organisation and practices. Trust, fair rules and efficient decision making are key things to solve. Technologies such as blockchain can help here, but it is useful to keep in mind that they are only as good as they are coded to be.

Selected articles and websites

Why Platform Cooperatives Can Be The Answer To A Fairer Sharing Economy

Platform Cooperativism Consortium

Bringing the Platform Co-op “Rebel Cities” Together: An Interview with Trebor Scholz:

Proposal: turn Twitter into a user-owned co-op

Skills for platform economy

Why is this important?

Platform economy requires a new set of skills. Understanding the big picture, interpreting information in the right context, networking and collaborating with people with diverse backgrounds in growing in importance. In addition, while being able to code and understand code is needed, it is more important to understand the consequences of digitalization and have the competence to design platforms that benefit the society.

Things to keep an eye on

The shift in skills needed may easily lead to growing inequalities between different regions but also between the old and young. Learning new skills related to platforms is not just for young students, but also for those in work life. In addition, platform thinking is not disrupting all industries at once, so there are differences between different fields. Educational platforms also challenge existing educational institutions.

Selected articles and websites

Design It Like Our Livelihoods Depend on It: 8 Principles for creating on-demand platforms for better work futures

Learning is earning in the national learning economy

The 10 skills you need to thrive in the Fourth Industrial Revolution