This signal post gives a short summary of a literature review on GDP and it’s usability as a measure in the increasingly digitalised economy. For more details, download the full report.

A measure for the manufacturing age

Gross Domestic Product was adopted in the 1940s, the age of manufacturing, to measure the strength of a country’s economy and it also became a proxy for well-being. It’s a measure of the monetary value of all goods and services produced by a country. A rapidly increasing portion of today’s economy is technology services, including platforms that offer “free/add-supported” products or act as international online intermediaries to facilitate the exchange of goods, services or information. By definition, the GDP doesn’t measure “free” products. In economic terms, the value a consumer gets from the “free”, and potentially higher quality products is measured by utility or consumer surplus, which is also not captured in GDP.

The slowing of GDP growth

While the GDP of most of the world’s economies has been increasing since its inception, the rate of GDP growth has slowed recently. More importantly, the growth rates of GDP per capita and GDP per hour worked (labour productivity) have also slowed. While the root cause of the slowdown in GDP growth has been debated for several decades, most economists agree that a portion of the slowdown is real and not solely an issue with capturing the growth of the platform and technology sector. Structural issues like demographics as well as the fact that past innovations like the electric motor likely had a larger impact on productivity than recent innovations are all contributing factors.

The uniqueness of the platform economy and the technology sector

While the reasons above partially explain the slowdown in GDP growth, many agree there is a growing proportion of the economy that isn’t being captured as part of GDP. There are a number of unique aspects of the platform economy and the technology sector that make it challenging to measure, manage, and ensure fair taxation. These include: ability to scale at low cost; “free/ad-supported” pricing models; borderless reach; blurred lines between consumers and producers; venture funding that encourages long-term market capitalisation over short-term profitability; digital services that replace physical products; and there’s a decreasing marginal contribution to GDP as the technology sector grows.

Uncaptured GDP

Given the unique aspects of the platform economy and the technology sector described above, it is possible that some aspects are having a negative influence on GDP growth while other aspects are having a positive influence that is difficult to capture using the current definition of GDP. The growth of the platform economy has been partially based on a culture of “free/low cost” products and services that provide utility and happiness to people beyond their economic value. This consumer surplus adds up to substantial uncaptured GDP.

This additional utility and happiness create a positive feedback loop that drives growth in the technology sector and the platform economy. As people seek to increase utility and happiness, they consume more in the platform economy which leads to its continued expansion as well as growth in uncaptured GDP.

Soft Innovation Resources

Understanding how to encourage the expansion of the platform economy may be key to increasing the rate of GDP growth. Watanabe, et al., postulate that countries (and companies) can increase their rate of growth by diverting a portion of their resources away from R&D and towards enabling Soft Innovation Resources (SIRs) as a complement to traditional R&D. These are soft resources that can be harnessed to drive innovation and growth at individual companies, which rolls up to growth at the country level.

Enablers of Soft Innovation Resources are listed below:

- Supra-Functionality: People seek out products and services where they experience satisfaction beyond utilitarian functional needs. They desire social, cultural, aspirational, tribal, and emotional benefits.

- Sleeping or Untapped Resources: These are existing resources that are under-utilized resulting in an unused capacity that may be spread sparsely and difficult to access without technology.

- Trust: People’s level of trust in various aspects of their lives, society, and the economy can affect their participation and contribution to innovation and the creation of economic value.

- Maximizing Gratification: Seeking gratification of needs is a key pillar of Maslow’s theories about motivation and human behaviour. As increasingly sophisticated needs are gratified, there is a desire to maintain and build upon the increased level of gratification.

- Assimilation and Self-Propagation: Sustainable growth can be obtained when past innovations are assimilated into future innovations, effectively creating a self-propagating cycle of innovation.

- Co-Evolution: The coupling of two or more items which then innovate and evolve along a common path.

The future of GDP measurement

Although the GDP measure has been revised over time, there is widespread recognition that more changes are needed if it’s to remain relevant as the digital economy grows. There is debate about how platforms and the digital economy are contributing to GDP and the amount of uncaptured GDP. For example, the US Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) concluded uncaptured GDP would increase the rate of GDP growth by less than 0.01% per year. On the other hand, Brynjolfsson, et al. developed a measure they call GDP-B and they concluded that the consumer surplus from Facebook alone would increase the rate of US GDP growth by 0.1% per year and platforms such as internet search, e-mail, and maps would contribute significantly more. And somewhere in between, an independent study commissioned by the UK government concluded that annual GDP growth is understated by 0.3% to 0.6%, largely due to the platform economy.

It’s clear there are wide-ranging opinions on the magnitude of uncaptured GDP. International organisations such as the OECD and World Economic Forum are also trying to bring clarity to the situation. Additionally, a number of measures are being developed such as the Human Development Index (United Nations) and the Better Life Index (OECD) with a focus on well-being to augment GDP.

Strategies for future growth

The slowdown in GDP growth is complicated and multi-faceted. Perhaps some of the structural impediments to growth can’t be mitigated. Perhaps because digital platforms and their ecosystems function as highly efficient intermediaries that increase the flow of goods and services at substantially lower costs, we’re experiencing a temporary downward adjustment and growth will resume from a new baseline. As a result of this complexity, strategies to encourage future growth are challenging and diverse.

At the country level, the literature suggests strategies such as: developing economic measures to supplement GDP and better inform public policy in the digital age; create policies to increase skills training and corporate technology purchases to increase adoption of new technologies; develop policies to encourage experimentation in new technologies and business models; focus on improving the quality and lowering the cost of healthcare and education; increase immigration; enable Soft Innovation Resources; and refine international taxation and shipping practices to increase fairness in the shipping and taxation of digital goods and services.

At the company level, the literature suggests strategies such as: lagging firms should invest in skills training and increase the adoption of new technologies; leading firms should include the enablement of Soft Innovation Resources into their R&D and product development activities; and expand current products and services into platforms and expand platforms into platform ecosystems.

Selected articles and websites

The Economist – Measuring Economies – The trouble with GDP

Harvard Business Review – How Should We Measure the Digital Economy?

OECD – Are GDP and Productivity Measures Up to the Challenges of the Digital Economy?

Robert Gordon – Declining American Economic Growth Despite Ongoing Innovation

Watanabe, et al. – Measuring GDP in the digital economy: Increasing dependence on uncaptured GDP

Tou, et al. – Soft Innovation Resources: Enabler for Reversal in GDP Growth in the Digital Economy

Additional references

MIT – GDP-B: Accounting for the Value of New and Free Goods in the Digital Economy

British Government – Independent Review of UK Economic Statistics: Final Report (2016)

US Bureau of Economics Analysis – Valuing ‘Free’ Media in GDP: An Experimental Approach

Investopedia – Definition of consumer surplus

OECD – Measuring the Digital transformation

World Economic Forum – Welcome to the age of the platform nation

Forbes – Uber will lower GDP

United Nations – Human Development Index

OECD – Better Life Index

OECD – Unified Approach to taxation in the digital economy

Takeaways from the Platform Economy Summit 2019

In this signal post I will share my takeaways from attending the Platform Economy Summit Europe in Frankfurt, September 17-18, 2019. The summit brought together business leaders, investors, policy makers and platform strategists to discuss opportunities and threats of platform-based business models. Political, technological and societal dimensions were also explored, especially from the European perspective, and a wide range of strategies to harness the potential of the platform economy were laid out.

The two-day summit featured inspirational in-depth talks by the platform economy experts and gurus, most notably by Professor Marshall Van Alstyne from MIT IDE and co-author of Platform Revolution Sangeet Paul Choudary. Success stories, lessons learned as well as future aspirations were shared by companies and organisations from all walks of life, such as Alibaba Group, Deutsche Bank, European Commission, World Economic Forum, Apigee, FoundersLane, MaaS Global and Amadeus. Lively panel discussions occasionally evolved into profound debates, and the interactive participation of the audience ensured all points of view were being heard.

Next I will summarise my main takeaways under the following statements:

- “The platform game has only just begun.”

- “There is no ONE platform strategy.”

- “Emerging technologies will rule in round two.”

- “The bold yet patient mindset will succeed.”

These statements reflect the overall tone of discussions at the summit, and I will explain them using what was heard and seen in the presentations, talks, panel discussions, message board conversations and polls, written materials and networking activities.

”The platform game has only just begun”

As discussed in one of our previous signal posts, the platform economy is still in its infancy, and we have only seen the very first success stories. This was also the message at the summit, and future potential across different sectors and industries was widely discussed. In fact, platforms have potential to transform all and any traditional industries but also to blur sectoral boundaries. Platform business is all about ecosystems (not egosystems) that allow different fields to collaborate and innovate something new.

Expected next steps in platform development assume tighter B2B ecosystems to form and blossom. Platforms and “platforms of platforms” will enable business relationships among competitors as well as complementors to evolve. From the European perspective the regulatory harmonisation and solid foundations in public digital infrastructure provide a good breeding ground for this. Unlike what we often hear in the mass media, various speakers at the summit saw European public sector initiatives as profoundly productive support actions to foster responsible and healthy platform business. Examples include national and EU-led actions to re-regulate and de-regulate, such as the GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) and PSD2 (Payment Services Directive 2). European Single Market was also seen as an encouraging environment for European platforms to grow in and scale up from, on the path from local or national to global business.

Silicon Valley may be the mecca of technological innovation, and China has recently established itself as the leading business model innovator. Europe can learns from these, but also highlight its own strengths, such as its special focus on social and societal value creation. Awareness of the various pros as well as cons of the platform economy is high in Europe and keeps growing, and this attitude supports balanced and responsible development of platform activities.

”There is no ONE platform strategy”

All companies, organisations, business sectors, industries and markets have their unique qualities, and consequently there cannot be one single platform strategy that would fit all. The “digital natives” that have grown into global platform giants are obviously very different from moderate-sized incumbents in traditional industries, local markets and long business traditions. Understanding of what types of platform strategies fit with different situations is growing, and an integral part of it is also to find your own role relative to other actors in the so called ecosystem economy.

The strengths and weaknesses of an organisation help determine the best platform strategy. The size, maturity, traditions, legacy, resources, capabilities and skills are all important factors. Not everyone needs to set up their own platform, and an important step is to assess which one of the basic roles in the platform economy could suit you: the orchestrator, partner or contributor. You also need to consider who you want to join forces with and experiment and collaborate with. And who do you want to challenge and compete against?

”Emerging technologies will rule in round two”

Discussions on the platform economy are often coloured with technologically visionary ideas on AI (artificial intelligence), machine learning, blockchain technologies, big data and APIs (application programming interfaces), cloud computing, IoT (internet of things), etc. These technologies will improve functionalities such as identity management, ecosystem coordination, fostering of openness and trust, decision assistance and anomaly detection. These and more opportunities were addressed at the Platform Economy Summit, and amazing future aspirations were laid out by speakers on how these advanced technologies will be harnessed in the future.

However, the message was also pretty clear that there is no need to procrastinate and wait for all of these technology solutions to mature, even if they will be game changers later on, in the “round two” of the platform economy. Currently available technologies are more than enough to get started with, and the first round of the platform economy game is in full swing. To get your platform strategy ready and implemented is the thing to do right now, and in practice this could mean for example getting a good understanding of what is the potential with data in your branch of business. There is static and dynamic data, and there is also primary and secondary data. APIs are an important tool in ecosystem building, and B2B API activity correlates well with business growth and success.

”The bold yet patient mindset will succeed”

The often repeated message of the summit was, that companies willing to embrace the platform economy should get started and crystallise their platform strategy as soon as possible. Studies show that even a “failed” platform strategy results in better financial outcomes than no strategy at all. Developing a platform strategy necessitates boldness, radically innovative thinking and support from the top management. A platform strategy needs to go beyond digitalisation and incremental improvements, with the aim to operationalise new business models enabled by platforms. It needs to be integrated into the overall corporate strategy and show willingness to change and rethink the old ways.

But even if a platform strategy requires risk taking and changes in many aspects, including the company culture, it does not need to mean suddenly abandoning the core business. Instead, the platform strategy could be implemented, for example, in a separate business unit that is granted the resources and support to explore and develop the company in its new role as an actor in platform ecosystems.

Lack of boldness and leadership were mentioned as the common delimiting factors in platform strategy uptake. But along the next steps, if platform opportunities were being explored, the consequent challenge was often the lack of patience in fostering platform business growth. We are so used to hearing the overnight success stories of global platform corporations that our expectations of the pace of growth may be unrealistic. Instead, a patient mindset is needed, so that innovation horizons are conquered one step at a time. Also, monitoring the development of platform initiatives may often require different performance metrics and KPIs than what the traditional business is measures with. Therefore new approaches and patience will be also needed in follow-up processes.

Selected articles and websites

Jacobides, Michael G. (2019). In the Ecosystem Economy, What’s Your Strategy? Harvard Business Review

MIT: Marshall Van Alstyne

Platform Economy Summit Europe

Platform Strategist: Sangeet Paul Choudary

Profiling of users in online platforms

This signal post drills into the topic of profiling of platform users. We will have a look at how information on users’ background together with data on their offline and online behaviour is used by platforms and allied businesses. On the one hand, profiling allows service providers to answer user needs and to tailor personalised content. On the other hand, being constantly surveyed and analysed can become too much, especially when exhaustive profiling efforts across platforms begin to limit or even control individuals based on evaluations, groupings and ratings. The ever increasing use of smart phones and apps, as well as use of artificial intelligence and other enabling technologies, are in particular accelerating the business around profiling, and individuals as well as regulators may find themselves somewhat puzzled in this game.

What is profiling all about?

In the context of the platform economy, we understand profiling as collecting, analysis and application of user data as a part of the functioning of a platform. This means that e.g. algorithms are used to access and process vast amounts of data, such as personal background information and records of online behaviour. The level of digital profiling can vary greatly, and a simple example would contain a user profile created by an individual and their record of activities within one platform. A more complex case could be a multi-platform user ID that not only records all of the user’s actions on several platforms but also makes use of externally acquired data, such as data on credit card usage.

The core purpose of profiling is for the platforms to simply better understand their customers and develop their services. User profiles for individuals or groups allow targeting and personalisation of the offering based on user needs and preferences, and practical examples of making use of this knowledge include tailoring of services, price-discrimination, fraud detection and filtering of either services or users.

Pros and cons of profiling

From the user perspective, profiling is often discussed regarding problems that arise. Firstly, the data collected is largely from sources other than the individuals themselves, and the whole process of information gathering and processing is often a non-transparent activity. The user may thus have little or no knowledge of what is being known and recorded of them or how their user profile data is analysed. Secondly, how profiles are made use of in platforms, as well as how this data may be redistributed and sold onwards, is a concern. Discrimination may apply not only to needs-based tailoring of service offering and pricing but extend into ethically questionable decisions based on income, ethnicity, religion, age, location, the circle of friends, gender, etc. It should also be acknowledged that profiling may lead to misjudgement and faulty conclusions, and it may be impossible for the user to correct and escape such situations. The third and most serious problem area with profiling is when data and information on users is applied in harmful and malicious ways. This involves, for example, intentionally narrowing down options and exposure of the user to information or services or aggressively manipulating, shaping and influencing user behaviour. In practice this can mean filter bubbles, fake news, exclusion, political propaganda, etc. And in fact, the very idea of everything we do online or offline being recorded and corporations and governments being able to access this information can be pretty intimidating. Let alone the risk of this information being hacked and used for criminal purposes. Add advanced data analytics and artificial intelligence to the equation and the threats seem even less manageable.

However, profiling can and should rather be a virtuous cycle that allows platforms to create more relevant services and tailor personalised, or even hyper-personalised, content. This means a smooth “customer journey” with easy and timely access to whatever it is that an individual finds interesting or is in need of. Profiling may help you find compatible or interlinked products, reward you with personally tailored offers and for example allow services and pricing to be adjusted fairly to your lifestyle. In the future we’re also expecting behavioural analytics and psychological profiling to be used increasingly in anticipatory functions, for example to detect security, health or wellbeing deviations. These new application areas can be important not only for the individual but the society as a whole. Imagine fraud, terrorism or suicidal behaviours being tactfully addressed at early stages of emergence.

Where do we go from here?

Concerns raised over profiling are inducing actions in the public and private sectors respectively and in collaboration. A focal example in the topic of data management in Europe is the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) (EU) 2016/679 that will be applied in all European Union Member States from 25 May 2018 onwards. This regulation addresses the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data. And even if launched as a European rather than a global initiative, the GDPR applies to all entities processing personal data of EU citizens, and many global players have in fact already claimed compliance in all their practices. Issues covered by the regulation include limiting the scope of personal data to be collected, the individual’s right to access data on them and detailed responsibilities for those processing personal data.

While the EU tries to manage the protection of personal data and thus bring transparency and fairness to profiling, the Chinese government is exploring a very different direction by being taking the lead in gradually introducing a Social Credit System. This model is at the moment being piloted, with the aim to establish the ultimate profiling effort of citizens regarding their economic and social status. Examples of the functioning of the credit system include using the data sourced from a multitude of surveillance sources to control citizens’ access to transport, schools, jobs or even dating websites based on their score.

Another type of initiative is the Finnish undertaking to build an alternative system empowering individuals to have an active role in defining the services and conditions under which their personal information is used. The IHAN (International Human Account Network) account system for data exchange, as promoted by the Finnish Innovation Fund Sitra, is designed analogously to the IBAN (International Bank Account Number) system used in banking. The aim with IHAN is to establish an ecosystem for fair human-driven data economy, at first starting in Finland and then extending to Europe and onwards. The plan entails creating common rules and concept for information exchange, and testing of the technical platform will be done together with pilots from areas of health, transport, agriculture, etc.

Selected articles and websites

Business Insider Nordic: China has started ranking citizens with a creepy ‘social credit’ system — here’s what you can do wrong, and the embarrassing, demeaning ways they can punish you

François Chollet: What worries me about AI

General Data Protection Regulation (EU) 2016/679 – EUR-Lex

Kirk Borne: Top Data Trends for 2018 – Part 1

Platform Value Now: Tackling fake news and misinformation in platforms

Sitra: Human-driven data economy

Wikipedia: Profiling (information science)

Wikipedia: Social Credit System

Wolfie Christl, Cracked Labs: Corporate Surveillance in Everyday Life

Tackling fake news and misinformation in platforms

The online world is increasingly struggling with misinformation, such as fake news, that is spreading in digital platforms. Intentionally as well as unintentionally created and spread false content travels fast in platforms and may reach global audiences instantaneously. To pre-screen, monitor, correct or control the spreading is extremely difficult, and often the remedial response comes only in time to deal with the consequences.

In this signal post we study the problem of misinformation in the platform economy but also list potential solutions to it, with forerunner examples. Defining and establishing clear responsibilities through agreements and regulation is one part of the cure, and technological means such as blockchain, reputation systems, algorithms and AI will also be important. Another essential is to support and empower the users to be aware of the issue and practice source criticism, and this can be done for example by embedding critical thinking skills into educational curricula.

Misinformation − the size of the problem

Fake news or misinformation, in general, is not a new phenomenon, but the online world has provided the means to spread it faster and wider with ease. Individuals, organisations and governments alike can be the source or target audience of misinformation, and fake contents can be created and spread with malicious intentions, by accident or even with the objective of entertaining (for example the news satire organization The Onion).

Digital online platforms are often the place where misinformation is being released and then spread by liking, sharing, information searching, bots, etc. The online environment has not yet been able to adopt means to efficiently battle misinformation, and risks and concerns involved vary from reputation damage to global political crises. The most pessimistic views even warn us of an “infocalypse”, a reality-distorting information apocalypse. Others talk about the erosion of civility as a “negative externality”. This view points out that misinformation could, in fact, be tackled by companies in the platform economy analogously to how negative environmental externalities are tackled by manufacturing companies. It has also been suggested that misinformation is a symptom of deep-rooted systemic problems in our information ecosystem and that such an endemic condition in this complex context cannot be very easily fixed.

Solutions − truth, trust and transparency

Remedies to fake news and misinformation are being developed and implemented, even if designing control and repair measures may seem like a mission impossible. Fake accounts and materials are being removed by social media platforms, and efforts to update traditional journalism values and practices in the platform economy are being initiated. Identification and verification processes are a promising opportunity to improve trust, and blockchain among other technologies may prove pivotal in their implementation.

Example: The Council for Mass Media in Finland has recently launched a label for responsible journalism, which is intended to help the user to distinguish fake content and commercials from responsible and trustworthy journalism. The label is meant for both online and traditional media that comply with the guidelines for journalists as provided by the council.

Algorithms and technical design in general will also have an important part to play in ensuring that platforms provide the foundation and structure that repels misinformation. Taking on these responsibilities also calls for rethinking business models and strategies, as demand for transparency grows. One specific issue is the “filter bubble”, a situation where algorithms selectively isolate users to information that revolves around their viewpoint and block off differing information. Platforms such as Facebook are already adjusting and improving their algorithms and practices regarding, for example, their models for advertising.

Example: Digital media company BuzzFeed has launched an “outside your bubble” feature, which specifically gives the reader suggestions of articles providing differing perspectives compared to the piece of news they just read.

Example: YouTube is planning to address misinformation, specifically by adding “information cues” with links to third party sources when it comes to videos covering hoaxes and conspiracy theories. This way the user will automatically have suggestions to access further and possibly differing information on the topic.

Selected articles and websites

BuzzFeed: He Predicted The 2016 Fake News Crisis. Now He’s Worried About An Information Apocalypse.

BuzzFeed: Helping You See Outside Your Bubble

Engadget: Wikipedia had no idea it would become a YouTube fact checker

Financial Times: The tech effect, Every reason to think that social media users will become less engaged with the largest platforms

Julkisen sanan neuvosto: Mistä tiedät, että uutinen on totta?

London School of Economics and Political Science: Dealing with the disinformation dilemma: a new agenda for news media

Science: The science of fake news

The Conversation: Social media companies should ditch clickbait, and compete over trustworthiness

The Onion: About The Onion

Wikipedia: Fake news

Wikipedia: Filter bubble

Public sector ambitions in the platform economy

Ecosystems in the platform economy can accommodate all and any stakeholders, and the public sector among other actors can decide on the degree of ambition in the role they want to take. The most lightweight option would be to simply follow the field and allow market driven development of platforms proceed. In a more active mode the public sector would monitor and react to upcoming challenges and, for example, adjust taxation and regulation to match with the new landscape. Further on, a genuinely proactive role would entail active support for platforms and participation as a partner in platforms. The most ambitious option would be to aim to become a forerunner and contribute to strategic steering of the platform economy development. In this role the public sector could take on responsibilities in ecosystem facilitation but also show the way by embedding public services and internal processes to platforms.

In this signal post we introduce a few examples of the public sector taking ambitious and active part in the platform economy. These cases exemplify how visions are being turned into the new normal and how implementation steps have been taken in Finland and Estonia. The three topics covered are (1) platforms of open public data (serving among others further platform development), (2) provision of public services in platforms and (3) the visionary idea of citizenship as a platform (and for sale).

Open public data

Open public data means information produced or administered by a public organisation, and it is made available free of charge for private and commercial purposes alike, very much in line with the platform economy thinking. In Finland, metadata of public open data is collated in the Avoindata.fi service and then the European Data Portal. Although ‘work in progress’, many forerunner examples of novel open data initiatives are already running or under preparation. Often regulatory changes are needed to proceed towards open data effectively yet safely and securely.

Example: The Finnish Transport Agency maintains the NAP service (National Access Point), where since the beginning of 2018 all passenger transport service providers are obliged to open up their data on their services. The foundation for the system was laid in the innovative regulatory update, the Act on Transport Services, and accessing this data in the service, maintained by the transport authority, is expected to accelerate development of, for example, more comprehensive journey planners and advanced transport services.

Example: The government is proposing in Finland a new act on the secondary use of health and social data, intended to enter into force in July 2018. It would pave the way for a centralised electronic licence service and a licensing authority for the secondary use of health and social data. Finland already has extensive high quality data resources that could be put to more flexible and secure use instead of the current situation of dispersed datasets in different information systems by different authorities. The new act aims to streamline data requests and access as well as improve data security and thus benefit research, innovation and business but also teaching, monitoring, statistics, official planning, etc.

Public services in platforms

Digitalisation, in general, has been widely adopted as a target in public service provision, but the platform economy provides an even wider opportunity to more efficient, more accessible and less bureaucratic services. Education and social services among others are already making first steps in employing platforms, and a platform of platforms could also be envisioned, enabling seamless information exchange and navigation between services. For example, imagine managing your academic milestones, entitlement to study grants or other social assistance as well as medical records or unemployment situation not using separate manual processes but interlinked platforms with one-stop-shop principle. For a first implementation step, platform synergies could be built along administrative branches, such as education, or along specific fields of activity, such as administrative processes linked to building, construction and environmental permits.

Example: Suomi.fi is an online service in Finland that functions as a portal to public services and information. Although not a fully developed platform of platforms, this online service already demonstrates the single point of access principle in action. Suomi.fi empowers the user to find and then access a multitude of public services as well as their information and authorisations. For example, you could use the service to check your vehicle registry information and, if necessary, communicate electronically with the authorities to update it.

Citizenship as a platform

One imaginative or even utopian idea is to bring not only public sector data or services into platforms but to provide and exercise citizenship as a platform. Ultimately this would mean that an individual could choose their preferred digital citizenship platform and thus be, for example, entitled to public services and subject to taxation according to this choice. Citizenship as a digital platform would allow individual value-based decisions on citizenship rather than based on criteria such as country of birth. While the full concept remains theoretical, the first partial applications are running.

Example: E-Residency is a government issued digital identity launched by the Republic of Estonia in late 2014. It allows entrepreneurs from anywhere around the world to set up and run a location independent business but does not entail, for example, tax residency or citizenship rights to reside in Estonia. This legal and technical platform is the first of its kind, and the digitally accessible user benefits include company registrations, document signing, online banking, etc. The system also contributes to more transparent financial footprint through monitoring of digital trails. Between the launch and February 2018, over 33 000 applicants from 154 countries have established over 5 000 companies as e-Residents.

Selected articles and websites

Avoindata.fi − Open Data and interoperabilty tools

European Data Portal

Finnish Transport Agency: Service providers of passenger transport can now store data in the NAP service

Ministry of Finance: Open data: Opening up access to data for innovative use of information

Ministry of Social Affairs and Health: Secondary use of health and social data

Republic of Estonia: eResidency – Become an e-resident

Suomi.fi – information and services for your life events

Wikipedia: e-Residency of Estonia

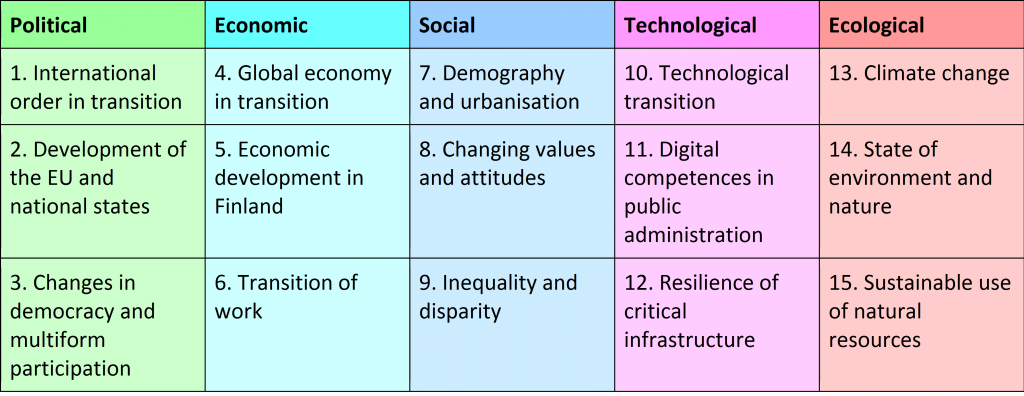

Interpreting the platform economy against landscape-level change factors

The Prime Minister’s Office in Finland published in late 2017 a list of change factors of the global landscape, with the aim to familiarise decision-makers as well as citizens with the changes and uncertainties we will face in the future. The result of fifteen key factors of change was produced in collaboration with experts across ministries and their strategy work. They also provide the basis for dedicated futures outlooks by various ministries to be published later in 2018.

The fifteen change factors each introduce the identified change and describe the situation until 2030. Additionally, alternative paths and development directions are offered. Rather than predictions, the change factors help prepare for various alternatives around the identified change topics, all the while acknowledging uncertainties.

In this signal post, the fifteen change factors are briefly analysed in the context of the platform economy. The idea was to formulate statements as questions and portray the alternative ways the change factor may be expressed in the platform economy. Some of the change factors can act as high level trends that steer platform development from afar, whereas others have very straightforward impact mechanisms. On the other hand, platforms themselves can influence the change factors and contribute to how the changes take place. The objective of this analysis is to help to map the potential with the platform economy regarding both opportunities and threats in the changing societal landscape. In fact, as the platform economy evolves, any of the issues identified may take a positive or negative turn or a combination of the two.

Political

- International order in transition

- Will the USA host as the basis for leading platform companies?

- Can China and the rest of Asia challenge the US leadership?

- Will platforms act as enabling tools in international policy-making?

- Will platforms be used as enabling tools for conflicts and corruption?

- Development of the EU and national states

- Will the EU develop into a competitive and uniformly close-knit platform economy?

- Could we face a failure of joint EU activities in the platform economy?

- Are there going to be nationally or regionally confined platform economies?

- Changes in democracy and multiform participation

- Will platforms act as enablers of accessible knowledge and the information society?

- Will platforms be used to spread polarisation and misinformation?

- Will platforms be employed as tools to societal participation in democracy?

Economic

- Global economy in transition

- Are we going to see globally reigning platform monopolies or local platform economies?

- Is the economic growth from platforms around the world going to be even or uneven?

- Will platforms support quick profits or sustainable growth?

- Economic development in Finland

- Will Finland succeed as a balanced platform economy on its own?

- Is Finland going to excel in its niche areas in the global platform economy?

- Will Finland remain a minor actor in the platform business?

- Transition of work

- Is all work going to be gig work on platforms?

- Could education, training and skills be provided on platforms on an on-demand basis?

Social

- Demography and urbanisation

- Can platforms bring along a counter-trend to urbanisation and migration?

- Could platforms help to solve challenges related to ageing?

- Will platforms be used as connectors between culturally or demographically differing groups?

- Changing values and attitudes

- How will ethics and values be incorporated into platforms?

- Could different platforms support variability in choices on lifestyles and values?

- Will platforms be used as a destructive force?

- Inequality and disparity

- Will platforms be employed to empower women and build equal opportunities globally?

- Will platforms be used to aggravate polarisation of individuals and nations?

- Can platforms contribute to accessible human health and wellbeing?

Technological

- Technological transition

- Will blockchain, AI, robots, etc. be employed successfully in platforms?

- Is the role of platforms and advanced technologies to be in control or as a subordinate?

- Could we face technological underachievement and failure of the platform economy?

- Will data be the currency of the future technological platforms?

- Digital competences in public administration

- Will the public sector be active in platform management and participation?

- Is public administration going to be incapable of deploying digital platforms in their own processes?

- Can the public sector keep up with platform markets?

- Resilience of critical infrastructure

- Will platforms bring intelligence into infrastructure management?

- Will we be able to ensure resilience regarding digital infrastructures and cyber security?

Ecological

- Climate change

- Could platforms and advanced technologies contribute to effective agreements in climate policy?

- Will digital platforms increase or decrease the overall environmental burden?

- Could the platform economy provide the means to survive with climate change impacts?

- State of environment and nature

- Could platforms facilitate monitoring of natural and built environments?

- Sustainable use of natural resources

- Could platforms be used as enabling tools for material and resource management, e.g. recycling?

- Will sharing platforms promote effectively sustainable, resource-efficient lifestyles and economies?

- Will unsustainable consumption patterns spread uncontrollably because of platforms?

- Are platforms, data and related technologies going to increase energy consumption exceedingly?

Selected articles and websites

Finland’s master plan for platform economy

A couple of weeks ago (October 2017) the Prime Minister’s Office, Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment and Finnish Funding Agency for Innovation Tekes published the national roadmap for digital platform economy for Finland. The first half of the report paints the present picture of the platform economy as a global phenomenon and Finland’s position in it. The second half drills into the national future aspirations for success and growth and introduces a vision and roadmap for Finland. Furthermore, an atlas of ten sector-specific roadmaps is presented and an action plan to fulfil the vision is outlined.

Top-down meets bottom-up

Finland is a pioneer in launching such a comprehensive national vision, roadmap and implementation plan for digital platform economy. Germany, Japan, Singapore and even the EU have touched upon the topic in their industrial or STI (science, technology and innovation) policies, but not with such focused dedication as Finland. The Finnish strategy is to harness platform economy as an enabling tool that has potential to generate growth for businesses as well as enhance productivity of the entire society. A key element of the vision is to develop national competitive edge out of the platform economy.

But why the choice of national and collective approach, when the leading platforms (from the US) have typically emerged as market-based business innovations? The Finnish initiative seems to embrace the platform economy as a wider phenomenon that covers the potential for value creation and capture not just for companies but for citizens and the state alike. Platform ecosystems therefore extend to all actors in the society, and governmental institutions can step up to take active part. According to the report, the foreseen role of public sector includes for example:

- facilitating society-wide dialogue and aligned national vision

- implementing a competitiveness partnership between public and private sectors

- strengthening the development and business environment for platforms

- developing the knowledge base, resources and tools

- showing example by open public data and platforms launched by the public sector

- other enabling support such as regulative measures.

In short, the Finnish hypothesis for how to accelerate and benefit from the platform economy is to activate both the bottom-up (innovators, businesses, individuals, etc.) and top-down (governments, authorities, regulators, etc.) stakeholders. No getting stuck in the chicken-and-egg dilemma, but getting started on all levels and in a nationwide public-private-partnership.

Other interesting messages

Strengthening of the knowledge base and education to support skills in the platform economy has received a lot of attention in the Finnish roadmap report. This covers both formal education as well as further training along the career path. What is especially highlighted is software design skills, but what about entrepreneurial mindset, data-driven innovativeness and cross-sectoral service thinking?

The value of data and the vast potential for its usage is also emphasized in the report. Data economy as a concept is being mentioned, and especially the role of the public sector is explored in terms of developing rules, providing common technical specifications as well as showing the way with public data resources.

Selected articles and websites

National roadmap report: Digitaalisen alustatalouden tiekartasto

Videos from the launching event (October 23, 2017): Suomi ja tekoäly alustatalouden aikakaudella

Further information: Suomi ja tekoäly alustatalouden aikakaudella

Problems with blockchain

A lot of hopes are placed on blockchain technology. They range from more modest aspirations, like ensuring secure food chains, to hyperbolic claims of creating economic and socio-political emancipation of humankind. Blockchain is said to offer a decentralised way of doing things while solving the problem of trust, which makes it very appealing for platform economy. What is often left out is the consideration of the negative consequences and the barriers to the wide adoption of the blockchain.

Negative consequences and barriers

The main negative impact on current implementations of blockchain relates to energy usage and consequential environmental and other impacts. Blockchains require a lot of computing power, which in turn requires a lot of electricity and cooling power. For example, for Bitcoin alone it has been calculated that by 2020 it might use as much energy as Denmark. While blockchain-based solutions – or cryptogovernance in general – has been offered as a way to alleviate some environmental problems by increasing traceability and ensuring ownership, the negative impact of these solutions to the environment should not be ignored.

The current architecture of the blockchain is high on energy consumption, and also has problems with scaling. The root problem is that all transactions in the blockchain have to be processed by basically everyone and everyone must have a copy of the global ledger. As the blockchain grows, more and more computing power and bandwidth are required and there is a risk of centralisation of decision making and validation power in the blockchain as only a few want to devote their efforts to keeping the blockchain running.

Along with problems of scaling, the issue of governance in blockchains is an unsolved challenge. Since there is no central actor, there needs to be mechanisms for solving disputes. The forking of The DAO and the discussions around it are a case in point. So while blockchain may offer new decentralised solutions to governance, the technology in itself is not enough.

Possible solutions

There are some solutions to the problem of scaling, such as increasing block size, sharding (breaking the global ledger into smaller pieces) and moving from proof of work consensus mechanism to proof of stake. One interesting solution that also decreases the computational power needed is Holochain. Instead of having a global ledger of transactions, in a holochain everyone has their own “blockchain”, and only the information needed to validate the chains is shared. This means basically that while a blockchain validates transactions with global consensus, a holochain validates people – or to be more precise, the authenticity of the chains of transactions people own.

Whatever the technological solution, a discussion on the negative consequences of blockchain is required to balance the hype. Do we want to implement blockchains everywhere no matter the environmental costs? What are the tradeoffs we are willing to make?

Selected articles and websites

- Hackernoon: Blockchains don’t scale

- Motherboard: Bitcoin could consume as much electricity as Denmark by 2020

- Coindesk: Blockchain’s 4 biggest assumptions

- Cointelegraph: Why blockchain alone cannot fix the privacy issue

- Cryptocoinnews: Blockchains will enhance the economic and socio-political emancipation of humankind

- Nature: The environment needs cryptogovernance

- Ensia: What can blockchain do for the environment?

- Ceptr: Holochain

Open innovation platforms

The concept of open innovation has been around for some time. The basic idea is that organisations open up their innovation processes to other companies as well as end-users and other stakeholders. Besides traditional face-to-face workshops and physical innovation spaces, digital platforms can be used to facilitate the matching between challenges and solutions, to prioritize ideas and to offer a place for collaboration and co-creation. Hackathons are an example of modern innovation platforms combining the best of the physical and digital innovation platforms.

Why is this important?

Open innovation platforms benefit at best the whole innovation ecosystem or network. Problems get solved quicker, new solutions are more suitable for end-users and stakeholder collaboration is enhanced. Digital solutions also broaden the outreach and allow participants of different backgrounds, expertise and location to contribute. While open innovation platforms have been used internally in companies and more openly in research and development, digital solutions are finding their way also to the public sector, especially to citizen engagement in local communities. This makes city development more transparent and opens up the door for smaller companies to compete in public procurement.

Things to keep an eye on

The current trend is towards more openness and from company ownership to network-based shared ownership of the innovation platform. Instead of a company having its own open innovation platform, the platforms are framed as ecosystem level collaboration spaces or solution marketplaces. On the public sector side open innovation platforms are used not just for seeking technological solutions to societal challenges, but also to foster social innovation. However, there are underlying questions that for the time being remain open, e.g. who owns the intellectual property at the end of the day, what are the benefits or compensation for participants or who all benefit from the platform .

Selected articles and websites

How open innovation platforms support city development?

TOP 10 Open Innovation Platforms

Open Ecosystem Network

The visibility of ethics in open innovation platforms

16 Examples of Open Innovation – What Can We Learn from Them?

Integrating Open Innovation Platforms in Public Sector Decision Making: Empirical Results from Smart City Research

Sitra: Ratkaisu 100

Digital activism

Internet, platforms and digital technologies offer new ways of spreading the message and organising action for different cause-driven movements and citizen activism. This digital activism is not limited to using platforms to support existing forms of activism, but also takes advantage of the new opportunities platforms give for distributing value and providing access for information.

Why is this important?

The clear benefit of platforms for activism is new tools for communicating, deliberating, organising and connecting. Platforms such as Enspiral support a collaborative culture, constructive deliberation and collective decision making. They pool together resources such as money, time and skills to promote a jointly agreed upon set of projects. There are also platforms aimed at explaining obscure policies or laws or doing the increasingly important fact-checking.

In addition to tools, there is a quieter form of digital activism, one aimed at changing societal structures of access of information and distribution of value. Projects building ad hoc digital networks or internet access points aim to circumvent restrictions on the access to information. Platform cooperatives aim to reshape the way value is distributed within the system. In general, the aim is to improve the possibilities of those that are respressed or silenced via digital cencorship, or left out in the winner-takes-all forms of digital economy.

Things to keep an eye on

Digital activism suffers from so called “clicktivism”, where people are eager to support a cause if it just means clicking a button. Then when nothing changes, people lose their faith also in other forms of activism. Therefore digital activism needs also “off-line” activism. At best, digital activism can support other forms of activism, at worst it can undermine them.

There are also interesting examples of what can emerge out of the interface between the physical and digital in the age of smart phones and ubiquitous connectivity. One such example is the “I’m being arrested” app, which is a panic button for demonstrators to let a preselected group of people know that they are in trouble. Using location aware and camera equipped smartphones provides new tools for ensuring transparency and fair treatment.

On the flipside, digital activism raises also questions about ethics and responsibilities. Whistleblowing and the leaking of classified information may be a necessary alarm call in some cases, and in others it may just do more harm through unintended side effects. It is worth noting where the activism rises and what are its underlying intentions. There is also the question of drawing a line between civil disobedience, mischief “for the lolz” and outright criminal activity.

A potential transformation may happen through the adoption of the tools for collective decision making and deliberation, as they find their way increasingly to more conventional arenas of decision making. It is interesting to see if they change the forms of governance.

Selected articles and websites

How a new wave of digital activists is changing society

Digital and Online Activism

Flex your political activist muscles with these resources

Mobile Justice (Team Human podcast with Jason van Anden)

Enspiral – more people working on stuff that matters

Loomio – making decisions together

See also our signal on persuasive computing