The world of healthcare has many facets and is constantly evolving. In this signal post, we look at how digital platforms are driving advances in healthcare delivery, hospital management, and the development of new treatments.

Harnessing the power of the cloud

Many organizations have transitioned to cloud-based solutions for key business functions such as accounting, sales force management, and maintaining customer data. Healthcare is a complex industry with many disparate service providers that people interact with throughout their lives. Family physicians, testing labs, specialists, and hospitals are just a few of the service providers responsible for patient care that are likely to use disparate paper-based and computerised systems that don’t talk to each other.

Finland is a world leader in Electronic Health Records (EHR) with its MyKanta platform. While Google and many other large players have cloud-based EHR platforms, a report from Health Europa highlights the benefits and challenges of replicating Finland’s success in other countries. Data privacy is a key issue for EHRs. When Google announced a partnership with Ascension, a large US-based healthcare provider, it triggered calls for oversight and stricter privacy provisions as more healthcare providers look to move their patient records to cloud-based platforms.

Augmenting diagnosis with Artificial Intelligence

Historically, doctors and specialists relied on years of experience, second opinions, and impressive memories to diagnose illnesses and decide on the best type of treatment. New tools are emerging to augment doctors’ ability to diagnose and treat disease.

Simply keeping track of new research and illnesses is a challenge for doctors and patients. Many patient-centred platforms include “symptom checkers” and provide medical reference information in simplified terms to help people determine if they have an illness and how it should be treated. While this can feed into some people’s medical paranoia, the platforms provide valuable information that helps people decide if their illness is serious. Some examples include Duodecim, WebMD, and MedLine Plus. Doctors can make use of more advanced platforms, including platforms like EvidenceAlerts that provide customised alerts when new research is published.

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning (AI and ML) platforms can analyse patterns in large amounts of data and build algorithms to make predictions. New platforms like Bering Research’s Brave AI are being piloted in the UK to give family doctors a tool that can analyse patient history and key medical markers to predict which patients are likely to experience a decline in health and need hospitalisation in the future. This allows doctors to start pro-actively managing patient health before a crisis occurs.

The strengths of AI and ML are also being used to interpret diagnostic images, such as ultrasounds and MRIs. While not yet capable of replacing humans, Google Health and Imperial College London have made progress using AI to review mammograms and detect breast cancer. Google has also been behind other advances such as diagnosing eye diseases and lung cancer. In Singapore, Automated Vascular Analysis (AVA) from See-Mode Technologies has been approved for clinical use to analyse vascular ultrasounds, before a final review by a human radiologist.

The Internet of Things (IoT) and the rise of smart health devices

Small, connected devices are making it possible to gather health information continuously and feed it into platforms that allow users and healthcare professionals to access and analyse the data. Many people already wear a smartwatch or carry a mobile phone. Sensors built into these devices and customised apps are being used to track heart rate and blood oxygen levels (FitBit), ensure medication adherence, and monitor the behaviour of seniors to identify cognitive decline (MindYou).

Specialised devices are emerging, such as Oura’s smart ring, that measures general health and can also be used to check for fevers and alert wearers of a potential COVID-19 infection. H2Care’s blood pressure reader resembles a small wristwatch and integrates with an app to provide trend tracking. Researchers have made several advances, such as a metabolite measuring device the size of wristwatch to analyse perspiration and assess the wearer’s body chemistry, a smart contact lens to help diabetics manage their condition, and electronic pills that monitor a patient’s digestive tract.

IoT and mobile communication are transforming hospitals into “Smart Hospitals”. Ambulances equipped with cameras, sensors, and devices like mobile MRIs will allow paramedics and specialists to begin treating complex cases before they arrive at the hospital. Once at the hospital, the Electronic Health Record (EHR) platform integrated with patient diagnostic and monitoring devices, along with AI-augmented care planning will allow entire care teams to provide seamless care. Advanced technologies like Augmented Reality/Robotic surgical devices and 3D printed organs and devices will dramatically improve patient outcomes. However, in addition to issues like data privacy and cybersecurity, most hospitals face fundamental challenges in implementing smart technologies, namely finding adequate funding and IT expertise.

Researching the future

Digital platforms are helping medical researchers manage the complexity, data, and collaboration associated with research while reducing the time it takes to bring new discoveries into clinical practice. Most medical research begins by searching for clues in large datasets from patients with a particular illness, or by analysing genetic data, or by looking for patterns in previous research, or by doing numerous experiments to identify chemicals (or combinations) that are effective. Using AI, Machine Learning, and data analytics, researchers are able to rely on platforms to do a lot of the initial work efficiently and quickly.

UK start-up, Exscientia was able to complete its research and begin human trials of a new drug in 12 months instead of the typical 5 years with traditional research methods. Researchers are hoping for an even shorter timeline to develop a Covid-19 vaccine. Apple is partnering with research institutions and using the ubiquity of its platform and the new Research app to enrol and track thousands, or even hundreds of thousands of people in broad research studies.

Once a treatment is in clinical trials, platforms like OpenClinica can manage participants and their data. Given the number of stakeholders involved in the clinical trial process and the sensitive nature of the data, Blockchain-enabled platforms are being considered to ensure the integrity of the trials.

Taking medical research to a more granular level using digital platforms is driving the emergence of personalised medicine. By sequencing an individual’s genome, analysing biomarkers, and considering other medications being taken, researchers can use CRISPR and other techniques to develop treatments tailored to that individual, that also avoid harmful drug interactions.

Selected Articles and Websites

The world of cloud-based services: storing health data in the cloud

Healthcare has many use cases for 5G and IoT but no infrastructure to support it

Finding the future of care provision: The role of smart hospitals

Personalized Medicine Is About to Go Mainstream With Big Implications for Health Care

AI Can Help Scientists Find a Covid-19 Vaccine

Apple launches three innovative studies in the new Research app

Is cyber security next to be disrupted by digital platforms?

In this signal, we will examine the driving forces, pressures and trends of digitization in the platform economy that are affecting the security of governments, corporations, and individuals. As digitization becomes more pervasive, we are at the stage where we can no longer afford even a brief outage without significant consequences. IBM in a research study interviewed 500 companies around the world who had experienced a data breach between July 2018 and April 2019. The study reported that the total average cost of a data breach totals to 3.92 M$ and that it takes as long as 279 days to identify and contain it.

At the same time as security threats are increasing, businesses are going through other digital transformations and expanding their digital ecosystems, shifting to cloud services and adding more devices to their networks (IoT, Internet of Things). All of these put tremendous pressure on IT infrastructure and required expertise of the staff. These challenges are discussed among different stakeholders in cyber security conferences like GCCS (Global Conference on CyberSpace) aiming to discuss the development of an international strategic cyber security framework. This is an indication of how complex and important an issue security has become and the need for international collaboration to aid in solving the problem.

Are there clear leaders leading the cyber security solutions?

Security has many aspects, such as physical security, identity management, authentication, access control, confidentiality, data integrity, and physical security to name a few. There is no one solution to meet all protection needs.

For example, take a look at Gartner’s August 2019 magic Quadrant for endpoint protection platforms, where companies are mapped in terms of completeness of their vision and their ability to execute. It seems that there is no particularly strong leader or challenger with a supreme ability to execute.

There is no one size fits all security product. Companies must knit together their own solutions. The problem is also compounded by manufacturers and vendors reluctance to share data. Even more concerning is the fact that raw data related to parts of critical infrastructure may be in the hands of private industry (for example power generation and distribution facilities, water, and wastewater treatment plants, transportation systems, oil and gas pipelines, and telecommunications infrastructure). This may prevent the countries national security teams from analyzing such data to aid in protecting this critical infrastructure and causing cyber blind spots.

Who owns cyber security in the enterprise?

Cyber security touches so many assets within an organization that it needs to definitely have oversight by the companies board of directors. At the same time, IT management and chief security officers need to learn how to communicate risks to CEO’s and boards. Given what assets need protecting is different for each company, it becomes a risk conversation and often needs to also involve the legal department.

Can blockchain help to increase the security of platforms?

A core feature of blockchain technology is encryption and decentralized data storage which can provide increased security for cloud platform infrastructures. Blockchain is being explored in the cyber security space to assist companies to maintain data integrity and to manage digital identities. PWC’s 2018 Global Blockchain Survey showed that 84% of the 600 executives surveyed across 15 territories indicated they were actively looking at blockchain. Blockchain could be a promising solution for security, but it is not yet applied widely.

What role will AI play in preventing cyber security breaches?

AI tools are being used to identify attempted, successful and failed cybersecurity attacks, learn from these attacks and update algorithms to detect these types of attacks in the future. AI may be used in endpoint protection software and vulnerability management software solutions in the future. Examples of some companies working on these types of solutions are IBM, Cylance, and Darktrace.

Examples of Security Platforms

Security is an actively developing field. In Finland alone, we can identify 375 companies dealing with security. F-Secure is one of the leading companies offering cybersecurity and privacy detection and response solutions. Given Finland’s reputation of being reliable, they have an opportunity to offer trustworthy solutions to the world.

Although we mentioned about not having a one size fits all integrated security platform there are companies with platform business models addressing pieces of the problems. Anomali Threat Platform integrates seamlessly with many security and IT systems to operationalize threat intelligence and their Developer SDK allows organizations to build custom integrations as well. GRF (Global Resilience Federation) builds, develops and connects security information-sharing communities. GRF is a provider and hub for cyber, supply chain, physical and geopolitical threat intelligence exchange between information sharing and analysis centers (ISACs), organizations (ISAOs) and computer emergency readiness/response teams (CERTs) from many different sectors and regions around the world. ILOQ advances in physical security with self-powered digital locking and mobile access management solutions that are revolutionizing the locking industry. Security Now RiskSense Solution is a vulnerability management and cyber risk platform, which helps companies manage their cyber risks through their vulnerabilities.

Selected Articles and Additional Websites

IBM Security (2019): Cost of a Data Breach Report

Internet Society (2017) GCCS – Global Conference on Cyber Space

Gartner (2019) GCCS – Global Conference on Cyber Space

The Hill – Dave Weinstein (2019): Cyber Blind Spots

PWC (2018): Blockchain in Business

IBM: Artificial intelligence for a smarter kind of cybersecurity

Cylance. AI Driven Threat Protection

Darktrace. Cyber AI Platform

Security Informed. Security Companies in Finland

Anomali. Secure Platform for trusted collaboration

F-secure

Global Resilience Federation. Multi Sector Security

Ilog. Self-powereed digital locking system

Security Now (2018). RiskSense Platform Demonstration

Cyber Balance Sheet (2018) Report Sponsored by Focal Point Data Risk

Wedge Networks (2016) Orestrated threat management

Gartner (2019). Top 7 Security and Risk Trends for 2019

Gartner 2019). 5 security questions boards will definitely ask

Components of trust in the platform economy: Ability, integrity and benevolence

Trust has always been a cornerstone to business success, and it has typically been developed through a personal contact with another person, organisation or brand. In this signal post we explore the importance of trust in the platform economy, where digitalisation provides a very different setting with new opportunities and threats. We use the well-established frame pieced together by Mayer et al. that views trust through its three components: ability, integrity and benevolence.

In the next sections we explain the three in the context of platforms and present some topical examples of trust problems and solutions. We focus on the viewpoint, where the user is the trustor and the platform is the trustee. However, it should be noted that these roles can also be studied in reverse, the user being the trustee and the platform the trustor. Furthermore, in platforms the trustor-trustee relationship is, additionally, often formed among two or more users or producers, or between users and producers.

Component 1: Ability

When we talk about trust, ability is the component which explains to what extent we believe that a platform embodies the competences needed to perform its tasks. Ability covers, for example, the technological skills and solutions to deliver the core service as well as preparedness regarding privacy, safety, data protection, etc.

Example: Review and rating systems are a well-established way in the platform economy to check the trustworthiness of platforms as well as their users and producers. Quality of services of all and any parties on supply or demand side can be evaluated, and reports of top performance and misbehaviour spread fast. Of course, even rating systems can be abused, but in practice they have proven very efficient.

Example: Blockchain has been envisioned to improve trust in terms of providing technological means to, for example, validate data integrity. In fact, it can be employed to promote the three factors of digital trust: security, identifiability and traceability.

Example: An important lesson the big platform giants have learnt is that when cyber-attacks happen, it is important to be open about it and inform the users of what happened and how the problem will be fixed. Preventive measures are naturally the top priority, but the user also needs to be able to trust a platform’s ability to react when hackers succeed.

Component 2: Integrity

Using integrity or honesty we assess whether a platform adheres to acceptable principles and keeps the promises it makes. The starting point for integrity is compliance with laws and transparent consistency in following service promises, delivery times, pricing, etc. Extended further, integrity measures how the values of the trustor and trustee (the user and the platform) meet.

Example: Trust can be compromised, when platforms (such as social media companies) collect and sell user data or allow fake news and fake identities in their systems. Even if such activities are legal, the essence of the issue is whether the platform is transparent and informs its users of what goes on and whether it takes an active or passive role in fixing possible problems.

Example: Trust and transparency can be fostered in platforms by engaging the user in the supply chain or sourcing process. For example, it is possible for the user in some platforms to follow their order in real-time and even take part in the decision-making (ingredients used, packaging materials, delivery times, etc.). Again, blockchain technology can be useful in these applications.

Component 3: Benevolence

Benevolence captures the intentions and motivations of a platform and whether these go beyond egocentric profit making. This component of trust blossoms when the user feels appreciated in a win-win relationship, where the value is created and distributed in a fair manner. Benevolence is all about caring, and it is the foundation for customer loyalty.

Example: A pattern we have seen with some of the current platform giants is how they grow from benevolent to predatory. At first such platforms emerge with a low-cost high-value offering, but trust may be compromised as personalised services become a trap, user policies and pricing are changed and the profit-seeking monopoly tightens its grip on both the producers and users.

Selected articles and websites

Afshar Vala, HuffPost Contributor platform: Blockchain: Every Company is at Risk of Being Disrupted by a Trusted Version of Itself.

Baldi Stefan, Munich Business School: Regulation in the Platform Economy: Do We Need a Third Path?

Frier Sarah, Bloomberg: Facebook Says Hackers Stole Detailed Personal Data From 14 Million People.

IBM: IBM Food Trust: trust and transparency in our food.

Kellogg Insight (The Trust Project): Cultivating Trust Is Critical—and Surprisingly Complex.

Mattila, Juri & Seppälä, Timo (7.1.2016). Digital Trust, Platforms, and Policy. ETLA Brief No 42.

Mayer, R., Davis, J., & Schoorman, F. (1995). An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust. The Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709-734.

Möhlmann Mareike and Geissinger Andrea (2018). Trust in the Sharing Economy: Platform-Mediated Peer Trust. In book: The Cambridge Handbook on Law and Regulation of the Sharing Economy.

Murray Iain: The Platform Economy Can Change the World.

Sangeet Paul Choudary, INSEAD Knowledge: The Dangers of Platform Monopolies.

Sitel Group: No Trust, No Business: Hub Forum 2018 Makes the Future of Commerce Clear.

The Conversation: Social media companies should ditch clickbait, and compete over trustworthiness.

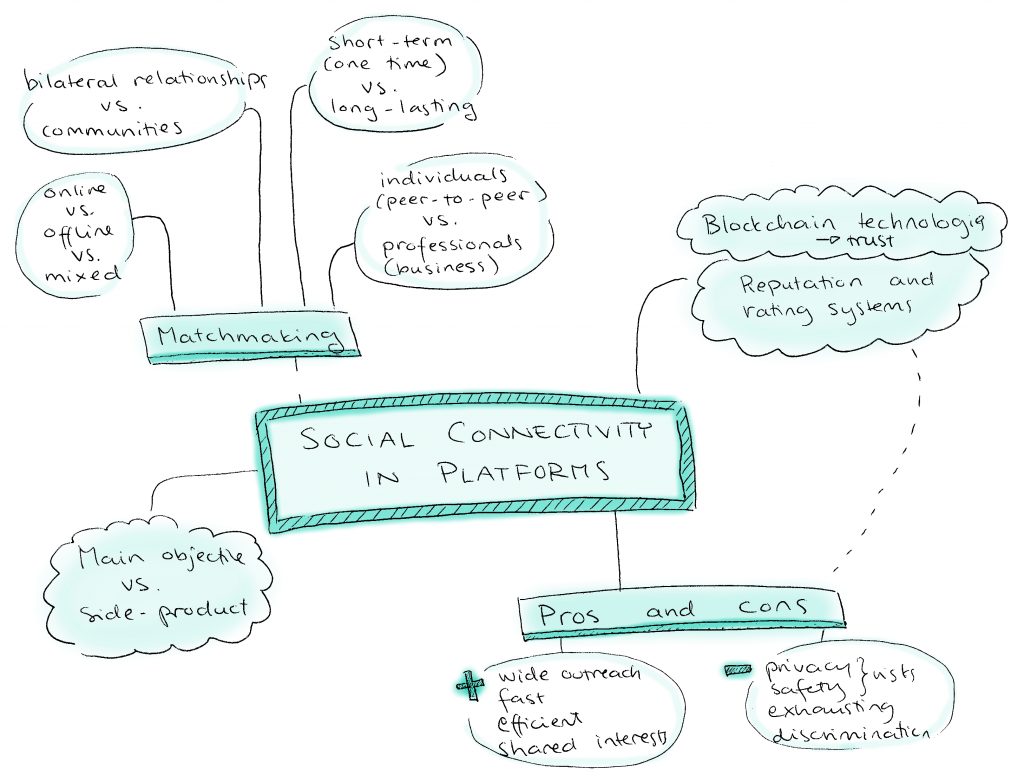

Social connectivity in platforms

Platforms are all about enabling connections to form between actors, typically producers and users of any given tangible or intangible commodity. But to what extent do these connections result in social value for individuals? There are of course social media platforms that by definition focus on maintaining or creating human relationships whether based on family ties, existing friendships, professional networking, dating or shared hobbies or interests. Interaction, communication and social ties nevertheless take place in other platforms too, and the positive and negative impacts of these may come as a rather unexpected side effect to the platform owner as well as users.

For example, ride-sourcing and hospitality platforms are virtual matchmakers, whose work comes to fruition when the virtual connection proceeds to a face-to-face meeting. A ride is then being shared with or a home is being rented to someone who only a little while back was a stranger. Many suchlike relationships remain one-time transactions, but they can also grow to regular exchanges over the platform or profound relationships outside the platform. Connectivity is as much a part of peer-to-peer platforms as professional and work-related platforms. You may form a personal connection with a specific IT specialist over the IT support system platform even if you never met them offline. Or supply chain business partnerships may evolve out of a one-time task brokerage platform transaction.

Why is this important?

The benefits of platform economy regarding social connectivity are the wide outreach and extremely fast and efficient matchmaking based on personal, professional of other mutual interests. In spite of complex technologies and big data flows, these social connections on platforms can be truly personalised, intimate and rewarding. The flipside of the coin is risks around privacy, safety and security. Reputation, review and rating systems are important ways to tackle these and could help to strengthen the sense of trust and community across user populations of platforms. In fact, one interesting finding of social connectivity in platforms is that relationships are maintained and formed bilaterally between the individual as well as among groups, communities and actor ecosystems. Short-term or long-lasting, these relationships often mix online and offline realities.

Additional concerns related to social connectivity in platforms is how much they eventually promote equality and fairness or if the social interaction is more of a burden than a benefit. Reputation and rating systems may result in unfair outcomes, and it may be difficult for entrants to join in a well-established platform community. Prejudices and discrimination exist in online platforms too, and a platform may be prone to conflict if it attracts a very mixed user population. In the ideal case, this works well, e.g. those affluent enough to attain property and purchase expensive vehicles are matched with those needing temporary housing or a ride. But in a more alarming case, a task-brokerage platform may become partial to assigning jobs based on criteria irrelevant to performance, e.g. based on socio-economic background. Platforms can additionally have a stressful impact on individuals if relationships formed are but an exhaustingly numberous short-term consumable.

Emerging technologies linked to platforms are expected to bring a new flavour to social aspects of the online world. The hype around blockchain, for example, holds potential to enhance and ease social connectivity when transactions become more traceable, fair and trustworthy. It has even been claimed that blockchain may be the game changer regarding a social trend to prioritise transparency over anonymity. Blockchain could contribute to individuals and organisations as users becoming increasingly accountable and responsible for any actions they take.

Things to keep an eye on

Besides technology developers and service designers’ efforts to create socially rewarding yet safe platforms, a lot also happens in the public sector. For example, European data protection regulation is being introduced, and the EU policy-making anticipates actions for governance institutions to mobilise in response to the emergence of blockchain technology.

An interesting initiative is also the Chinese authorities’ plan for a centralised, governmental social credit system that would gather data collected from individuals to calculate a credit score that could use in any context such as loans applications or school admissions. By contrast, the US has laws that are specifically aimed to prevent such a system, although similar small-scale endeavours by private companies do to some extent already exist.

Selected articles and websites

Investopedia: What Is a Social Credit Score and How Can it Be Used?

General Data Protection Regulation (EU) 2016/679 – EUR-Lex

European Parliament: What if blockchain changed social values?

European Parliament: How blockchain technology could change our lives

Rahaf Harfoush: Tribes, Flocks, and Single Servings — The Evolution of Digital Behavior

Koen Frenken, Juliet Schor (2017): Putting the sharing economy into perspective, Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions

Paolo Parigi, Bogdan State (2014): Disenchanting the World: The Impact of Technology on Relationships

Persuasive computing

In the aftermath of the US election, the power of social media filter bubbles and echo chambers has again evoked discussion and concern. How much can algorithms influence our behaviour?

Why is this important?

Data is a key part of the functioning of any platform, and analysis and filtering of data streams allows, for example, tailoring of the platform’s offering based on user data. This is evident in content platforms such as Facebook or Youtube, which learn from your behaviour and customise the user view and suggested contents accordingly. This filtering for personalised experience is valuable and helps the user navigate in their areas of interests, but there are also various drawbacks. Filtering and especially its invisibility can cause ‘filter bubbles’, where the user experience is threatened to limit to information that reinforces existing beliefs. This leads to polarization. What is even more troubling is that the algorithms can be tweaked to manipulate the feelings of users, according to a 2014 study done by Facebook without the users knowing.

Things to keep an eye on

The debate is now on-going as to how much algorithms can affect our actions. Some claim that the analysis and manipulation of social media feeds was instrumental in the US elections, while some say that the claims are overrated and the hype mostly benefits the analytics companies. In any case, the filtering of data is not inconsequential and there are increasing calls for more transparency to the filtering algorithms as well as for the ownership of the behavioural data collected through platforms. In part this issue becomes more and more topical with the advances in artificial intelligence, which makes data analysis more sophisticated and accessible. There are also interesting experiments – often with artistic goals – in confusing the algorithms in order to make the data they collect unusable by the platform owner.

Selected articles and websites

Will Democracy Survive Big Data and Artificial Intelligence?

The Rise of the Weaponized AI Propaganda Machine

The Truth About The Trump Data Team That People Are Freaking Out About

Robert Mercer: the big data billionaire waging war on mainstream media

How to hide your true feelings from Facebook

Persuading Algorithms with an AI Nudge

Social impacts of the platform economy

Platforms create value well beyond economic profits, and the topic of social and societal impacts resulting from the emerging platform economy has been getting more and more attention lately. Platform economy undoubtedly has both positive and negative impacts on individuals and families as well as wider communities and entire societies. However, the range and depth of these impacts can only be speculated, as only very early evidence and research on the topic has been produced. After all, the platform economy is only in its infancy.

Why is this important?

Platforms have potential to address major societal challenges such as those connected to health, transport, demographics, resource efficiency and security. They could massively improve our individual daily lives as well as contribute to equal opportunities and progress in developing economies. On the other hand, platform economy can result in negative impacts in the form of disruptions and new threats. Privacy and safety concerns have deservedly been acknowledged, and other possible risks include those related to social exclusion, discrimination and the ability of policies and regulations to manage with whatever platform economy may bring about.

Some examples of positive and negative social impact categories of the platform economy include the following, which may distribute equally, create further division or bridge the gap among various social segments:

- employment and unemployment

- livelihood and wealth

- education and training

- skills, knowledge and competences

- health and physical wellbeing

- mental health and wellbeing

- privacy, safety and security

- social inclusion or exclusion, access to services, etc.

- new social ties and networks, social mixing

- social interaction and communication: families, communities, etc.

- behaviour and daily routines

- living, accommodation and habitat

- personal identity and empowerment

- equality, equity and equal opportunities or discrimination

- citizen participation, democracy

- sufficiency or lack of political and regulatory frameworks.

Platforms may have very different impacts on different social groups, for example, based on age, gender, religion, ethnicity and nationality. Socioeconomic status, i.e. income, education and occupation, may also play an important role in determining what the impacts are, although it is also possible that platform economy balances out the significance of suchlike factors. One important aspect requiring special attention is how to make sure that vulnerable groups, such as the elderly or those with disabilities or suffering from poverty, can be included to benefit from the platform economy.

Things to keep an eye on

Value captured and created by platforms is at the core of our Platform Value Now (PVN) project, and there are several other on-going research strands addressing social and societal impacts of the platform economy. One key topic will be to analyse and assess impacts of the already established platform companies and initiatives, which necessitates opening the data for research purposes. To better understand the impacts and how they may develop as platform economy matures is of upmost importance to support positive progress and to enable steering, governance and regulatory measures to prevent and mitigate negative impacts.

Selected articles and websites

Koen Frenken, Juliet Schor, Putting the sharing economy into perspective, Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, (2017)

The Rise of the Platform Economy

Uber and the economic impact of sharing economy platforms

VTT Blog: Openness is the key to the platform economy

SUSY project: Solidarity economy

Technophobia – fear of technology

Although new technology intrigues us and makes us curious about what can be achieved with it, the flipside of the human reaction to anything new is suspicion and even fear. Technophobia means fear of technology, and it can stem, for example, from not fully understanding how something works, possibility of danger and negative impacts or risk of malicious misuse. Another flavour of technophobia is anxiety over our personal competences to deal with new technologies and the downright possibility of social exclusion if we lack the access or skills to adopt them.

Why is this important?

Some of the technology fears connected to the platform economy have been around for a long time, and they apply to pretty much any technologies linked to machines and computing. The archetype of suchlike concerns is the fear of losing our jobs because of automation, something that has been a worry for well over a century.

Another major concern in the context of platform economy is how the disruption to economy will impact us as individuals (for example moving from regulated labour market to the gig economy), as businesses (for example smaller companies being bulldozed by large platform corporations) or as society (for example governments trying to keep up with regulation, legislation and fiscal needs related to platforms).

Fears do not either escape the indirect risks and negative impacts that may arise with platformisation, such as loss of knowledge and survival mechanisms if digitalised assets are destroyed or if there’s a prolonged power cut. Intentional misuse and criminal activity is also a scare experienced by many, and evolving platform configurations may indeed be extremely vulnerable.

Examples of specific fears include:

- Fear of technology eliminating jobs and the need for human workers.

- Fear of technology taking over the human (individual or society).

- Fears related to privacy and cyber security.

- Fear of losing control and getting lost in the technology mesh.

- Fear of not learning the skills or not having access to use a technology.

- Fear of dependence and not surviving without the technology (for example in case of a power cut).

- Fear of negative social and societal impacts (for example lack of face-to-face interaction).

- Fears related to fast and vast information flows (for example validity of news).

- Fear of governments not having the means to monitor and control malicious and criminal activity related to new technologies.

Things to keep an eye on

The important thing is to try understand the root causes of fear of technology in the context of platform economy, regardless of whether the threats are real or perceived. Also, it should we noted that technophobia may influence not only consumers but businesses and policy-makers alike. Through addressing technology-related concerns appropriately we can ensure that individuals as well as companies and other organisations have the courage to make the best of the platform economy opportunities. On the other hand, the assessment of fears helps us to pinpoint risks and vulnerabilities that need to be fixed in technological, regulatory or other terms. To dispel mistrust, impartial and validated information to support technology proficiency and awareness is needed. Similarly important are also investments in for example digital security and technology impact assessment.

Selected articles and websites

Robots have been about to take all the jobs for more than 200 years. Is it really different this time?

The Victorians had the same concerns about technology as we do

Fear of Technology

Hot Technology Pilots in 2016 – Fear & Chaos in Technology Adoption

Why do we both fear and love new technology?

Americans Are More Afraid of Robots Than Death. Technophobia, quantified

Ever-present threats from information technology: the Cyber-Paranoia and Fear Scale

The access – Platform economy: Creating a network of value

Choosing a Future in the Platform Economy: The Implications and Consequences of Digital Platforms

Collapse of the internet

Why is this important?

Internet is the backbone of almost all platforms. However, it’s reliability is facing problems related to capacity and security. The physical infrastructure is struggling to keep up with rising amounts of traffic. Perhaps more importantly, the domain name servers have been increasingly under serious distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks. If the reliability of internet is challenged many of the platforms we take for granted will not work. Platforms will then have to seek other networks or ways to exchange information.

Things to keep an eye on

The rise in Internet of Things (IoT) brings to the net a multitude of connected devices, usually with low security, enabling ever larger DDoS attacks. If these attacks succeed in crippling the name servers, the internet will eventually split into separate smaller networks. DDoS attacks can also more easily affect the websites and servers of individuals or organisations. The scarcity of capacity may also challenge net neutrality.

Selected articles and websites

The internet of stings

10 things to know about the October 21 IoT DDoS attacks

Optical Fibers Getting Full

When Will the Internet Reach Its Limit