In this signal, we will examine the driving forces, pressures and trends of digitization in the platform economy that are affecting the security of governments, corporations, and individuals. As digitization becomes more pervasive, we are at the stage where we can no longer afford even a brief outage without significant consequences. IBM in a research study interviewed 500 companies around the world who had experienced a data breach between July 2018 and April 2019. The study reported that the total average cost of a data breach totals to 3.92 M$ and that it takes as long as 279 days to identify and contain it.

At the same time as security threats are increasing, businesses are going through other digital transformations and expanding their digital ecosystems, shifting to cloud services and adding more devices to their networks (IoT, Internet of Things). All of these put tremendous pressure on IT infrastructure and required expertise of the staff. These challenges are discussed among different stakeholders in cyber security conferences like GCCS (Global Conference on CyberSpace) aiming to discuss the development of an international strategic cyber security framework. This is an indication of how complex and important an issue security has become and the need for international collaboration to aid in solving the problem.

Are there clear leaders leading the cyber security solutions?

Security has many aspects, such as physical security, identity management, authentication, access control, confidentiality, data integrity, and physical security to name a few. There is no one solution to meet all protection needs.

For example, take a look at Gartner’s August 2019 magic Quadrant for endpoint protection platforms, where companies are mapped in terms of completeness of their vision and their ability to execute. It seems that there is no particularly strong leader or challenger with a supreme ability to execute.

There is no one size fits all security product. Companies must knit together their own solutions. The problem is also compounded by manufacturers and vendors reluctance to share data. Even more concerning is the fact that raw data related to parts of critical infrastructure may be in the hands of private industry (for example power generation and distribution facilities, water, and wastewater treatment plants, transportation systems, oil and gas pipelines, and telecommunications infrastructure). This may prevent the countries national security teams from analyzing such data to aid in protecting this critical infrastructure and causing cyber blind spots.

Who owns cyber security in the enterprise?

Cyber security touches so many assets within an organization that it needs to definitely have oversight by the companies board of directors. At the same time, IT management and chief security officers need to learn how to communicate risks to CEO’s and boards. Given what assets need protecting is different for each company, it becomes a risk conversation and often needs to also involve the legal department.

Can blockchain help to increase the security of platforms?

A core feature of blockchain technology is encryption and decentralized data storage which can provide increased security for cloud platform infrastructures. Blockchain is being explored in the cyber security space to assist companies to maintain data integrity and to manage digital identities. PWC’s 2018 Global Blockchain Survey showed that 84% of the 600 executives surveyed across 15 territories indicated they were actively looking at blockchain. Blockchain could be a promising solution for security, but it is not yet applied widely.

What role will AI play in preventing cyber security breaches?

AI tools are being used to identify attempted, successful and failed cybersecurity attacks, learn from these attacks and update algorithms to detect these types of attacks in the future. AI may be used in endpoint protection software and vulnerability management software solutions in the future. Examples of some companies working on these types of solutions are IBM, Cylance, and Darktrace.

Examples of Security Platforms

Security is an actively developing field. In Finland alone, we can identify 375 companies dealing with security. F-Secure is one of the leading companies offering cybersecurity and privacy detection and response solutions. Given Finland’s reputation of being reliable, they have an opportunity to offer trustworthy solutions to the world.

Although we mentioned about not having a one size fits all integrated security platform there are companies with platform business models addressing pieces of the problems. Anomali Threat Platform integrates seamlessly with many security and IT systems to operationalize threat intelligence and their Developer SDK allows organizations to build custom integrations as well. GRF (Global Resilience Federation) builds, develops and connects security information-sharing communities. GRF is a provider and hub for cyber, supply chain, physical and geopolitical threat intelligence exchange between information sharing and analysis centers (ISACs), organizations (ISAOs) and computer emergency readiness/response teams (CERTs) from many different sectors and regions around the world. ILOQ advances in physical security with self-powered digital locking and mobile access management solutions that are revolutionizing the locking industry. Security Now RiskSense Solution is a vulnerability management and cyber risk platform, which helps companies manage their cyber risks through their vulnerabilities.

Selected Articles and Additional Websites

IBM Security (2019): Cost of a Data Breach Report

Internet Society (2017) GCCS – Global Conference on Cyber Space

Gartner (2019) GCCS – Global Conference on Cyber Space

The Hill – Dave Weinstein (2019): Cyber Blind Spots

PWC (2018): Blockchain in Business

IBM: Artificial intelligence for a smarter kind of cybersecurity

Cylance. AI Driven Threat Protection

Darktrace. Cyber AI Platform

Security Informed. Security Companies in Finland

Anomali. Secure Platform for trusted collaboration

F-secure

Global Resilience Federation. Multi Sector Security

Ilog. Self-powereed digital locking system

Security Now (2018). RiskSense Platform Demonstration

Cyber Balance Sheet (2018) Report Sponsored by Focal Point Data Risk

Wedge Networks (2016) Orestrated threat management

Gartner (2019). Top 7 Security and Risk Trends for 2019

Gartner 2019). 5 security questions boards will definitely ask

Elections, campaigns and voting in the platform economy

This coming spring in Finland is going to entail lively political discussions. The campaigns for the Parliamentary Elections (April 2019) are already in full swing. And after having dealt with domestic issues, the European Elections will follow (May 2019). Political debates are taking place in the media as well as workplaces, schools and other arenas where people meet. This includes also digital meeting places, and platforms of different type are growingly important in delivering political messages with wide outreach.

In this signal post, we will discuss three aspects of how the platform economy is facilitating political discourse. We will identify both positive and negative impacts on democracy, especially at the time of elections. The three topics are:

- targeted political campaigns

- fake news in politics

- electronic and online voting.

Targeted political campaigns

Digitalisation and the platform economy are changing the way that political campaigns are carried out nowadays. Voting advice applications act as platforms for candidates and parties to declare their agendas and for voters to find a match from their point of view. Another way to benefit from the wide outreach enabled by platforms is for electoral candidates to be active on social media.

While the platform economy promotes broad societal discussions and better informed decision-making, new types of problems also arise. Organized mass campaigns are masked as non-political one-to-one chitchat. Data about voters is being collected, and platform giants together with consultancies like Cambridge Analytica have been known to take targeted political campaigns and personalized adverts to a whole new level. There is little transparency, and the ways used to influence voting decisions are questionable.

It is very appropriate that platform-based solutions have been developed to tackle these issues. In Finland, the Vaalivahti initiative has been launched to help citizens identify when political adverts are displayed on Facebook. A simple browser extension, based on the software developed by Who Targets Me, needs to be installed, and an analysis of political ads and why you were being targeted is provided. The platform maintains an up-to-date database of targeted political campaigns, which is open also for researchers and journalists to examine.

Fake news in politics

The 2016 US presidential election, and the alleged fake news attacks surrounding it, was a big wake-up call around the world. Studies and investigations have been conducted with the aim to reveal what really happened, how much fake news and misinformation was being released and by whom, what the real influence on voters was and whether the very election result was affected. One example is the recent study that suggests that the exposure of the average American to pro-Trump fake news was higher than that of pro-Clinton, but the authors emphasize that rash conclusions cannot be made based on this knowledge.

Fake news by foreign or domestic, political or economic actors has the potential to disrupt democracy, especially close to elections. The forms adopted range from fake news promoting to bashing one candidate, but they may also intend to inhibit political speech and suppress voting altogether. Social media and other platforms are being used as the tools and means to distribute fake news, and regulatory governance and rule setting may be needed to address these issues.

An example of suggestions to fix problems with regulatory measures is to require transparency of political advertising on digital media by informative real-time ad disclosure. Such data includes the sponsor, money spent, targeting parameters, etc. This real-time information provided along with the ad should also be compiled and stored for later review.

Electronic and online voting

Platforms can also facilitate the casting and counting of votes by using electronic means. For example, an electronic voting platform could build on voting machines at polling stations. Or, take a few more steps forward, an online voting platform could allow those entitled to vote exercise their right from anywhere, using any device as long as they can connect to the internet.

In Finland, the topic of electronic voting has been discussed from the early 2000s on and several studies and pilots have been conducted by the Ministry of Justice. Electronic voting at polling stations was trialled in three municipalities in the 2008 municipal elections, but problems were encountered in registering votes. Work to develop electronic voting was thus discontinued around 2010, but discussions were reopened in 2016. A working group was then appointed, and a feasibility study on the introduction of online voting in Finland was published in 2017. The conclusion was that even though viable electronic voting systems already existed, they did not meet the requirements and risks outweighed benefits. Core problems included, for example, the reliability of the system and guaranteeing verification and election secrecy at the same time.

New technologies, such as blockchain, may however help solve the issues mentioned above. Blockchain could be used to fight electoral fraud and vote buying while ensuring integrity and inclusiveness. Service development with blockchain-based voting platforms is vibrant, and pilots are showing great promise.

Selected articles and websites

Greenspon Edward and Owen Taylor (2018). Democracy Divided: Countering Disinformation and Hate in the Digital Public Sphere

Hunt Allcott and Gentzkow Matthew (2017). Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31 (2): 211-36

Ministry of Justice. 2017. Online voting in Finland, A feasibility study

Ministry of Justice. Electronic voting in Finland

Palermo Frank, Forbes. Is Blockchain The Answer To Election Tampering?

Palmisano Tonino, The Cryptonomist: Voting in the days of Blockchain technology

Vaalivahti

Who Targets Me

Wikipedia. Voting advice application

Components of trust in the platform economy: Ability, integrity and benevolence

Trust has always been a cornerstone to business success, and it has typically been developed through a personal contact with another person, organisation or brand. In this signal post we explore the importance of trust in the platform economy, where digitalisation provides a very different setting with new opportunities and threats. We use the well-established frame pieced together by Mayer et al. that views trust through its three components: ability, integrity and benevolence.

In the next sections we explain the three in the context of platforms and present some topical examples of trust problems and solutions. We focus on the viewpoint, where the user is the trustor and the platform is the trustee. However, it should be noted that these roles can also be studied in reverse, the user being the trustee and the platform the trustor. Furthermore, in platforms the trustor-trustee relationship is, additionally, often formed among two or more users or producers, or between users and producers.

Component 1: Ability

When we talk about trust, ability is the component which explains to what extent we believe that a platform embodies the competences needed to perform its tasks. Ability covers, for example, the technological skills and solutions to deliver the core service as well as preparedness regarding privacy, safety, data protection, etc.

Example: Review and rating systems are a well-established way in the platform economy to check the trustworthiness of platforms as well as their users and producers. Quality of services of all and any parties on supply or demand side can be evaluated, and reports of top performance and misbehaviour spread fast. Of course, even rating systems can be abused, but in practice they have proven very efficient.

Example: Blockchain has been envisioned to improve trust in terms of providing technological means to, for example, validate data integrity. In fact, it can be employed to promote the three factors of digital trust: security, identifiability and traceability.

Example: An important lesson the big platform giants have learnt is that when cyber-attacks happen, it is important to be open about it and inform the users of what happened and how the problem will be fixed. Preventive measures are naturally the top priority, but the user also needs to be able to trust a platform’s ability to react when hackers succeed.

Component 2: Integrity

Using integrity or honesty we assess whether a platform adheres to acceptable principles and keeps the promises it makes. The starting point for integrity is compliance with laws and transparent consistency in following service promises, delivery times, pricing, etc. Extended further, integrity measures how the values of the trustor and trustee (the user and the platform) meet.

Example: Trust can be compromised, when platforms (such as social media companies) collect and sell user data or allow fake news and fake identities in their systems. Even if such activities are legal, the essence of the issue is whether the platform is transparent and informs its users of what goes on and whether it takes an active or passive role in fixing possible problems.

Example: Trust and transparency can be fostered in platforms by engaging the user in the supply chain or sourcing process. For example, it is possible for the user in some platforms to follow their order in real-time and even take part in the decision-making (ingredients used, packaging materials, delivery times, etc.). Again, blockchain technology can be useful in these applications.

Component 3: Benevolence

Benevolence captures the intentions and motivations of a platform and whether these go beyond egocentric profit making. This component of trust blossoms when the user feels appreciated in a win-win relationship, where the value is created and distributed in a fair manner. Benevolence is all about caring, and it is the foundation for customer loyalty.

Example: A pattern we have seen with some of the current platform giants is how they grow from benevolent to predatory. At first such platforms emerge with a low-cost high-value offering, but trust may be compromised as personalised services become a trap, user policies and pricing are changed and the profit-seeking monopoly tightens its grip on both the producers and users.

Selected articles and websites

Afshar Vala, HuffPost Contributor platform: Blockchain: Every Company is at Risk of Being Disrupted by a Trusted Version of Itself.

Baldi Stefan, Munich Business School: Regulation in the Platform Economy: Do We Need a Third Path?

Frier Sarah, Bloomberg: Facebook Says Hackers Stole Detailed Personal Data From 14 Million People.

IBM: IBM Food Trust: trust and transparency in our food.

Kellogg Insight (The Trust Project): Cultivating Trust Is Critical—and Surprisingly Complex.

Mattila, Juri & Seppälä, Timo (7.1.2016). Digital Trust, Platforms, and Policy. ETLA Brief No 42.

Mayer, R., Davis, J., & Schoorman, F. (1995). An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust. The Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709-734.

Möhlmann Mareike and Geissinger Andrea (2018). Trust in the Sharing Economy: Platform-Mediated Peer Trust. In book: The Cambridge Handbook on Law and Regulation of the Sharing Economy.

Murray Iain: The Platform Economy Can Change the World.

Sangeet Paul Choudary, INSEAD Knowledge: The Dangers of Platform Monopolies.

Sitel Group: No Trust, No Business: Hub Forum 2018 Makes the Future of Commerce Clear.

The Conversation: Social media companies should ditch clickbait, and compete over trustworthiness.

Profiling of users in online platforms

This signal post drills into the topic of profiling of platform users. We will have a look at how information on users’ background together with data on their offline and online behaviour is used by platforms and allied businesses. On the one hand, profiling allows service providers to answer user needs and to tailor personalised content. On the other hand, being constantly surveyed and analysed can become too much, especially when exhaustive profiling efforts across platforms begin to limit or even control individuals based on evaluations, groupings and ratings. The ever increasing use of smart phones and apps, as well as use of artificial intelligence and other enabling technologies, are in particular accelerating the business around profiling, and individuals as well as regulators may find themselves somewhat puzzled in this game.

What is profiling all about?

In the context of the platform economy, we understand profiling as collecting, analysis and application of user data as a part of the functioning of a platform. This means that e.g. algorithms are used to access and process vast amounts of data, such as personal background information and records of online behaviour. The level of digital profiling can vary greatly, and a simple example would contain a user profile created by an individual and their record of activities within one platform. A more complex case could be a multi-platform user ID that not only records all of the user’s actions on several platforms but also makes use of externally acquired data, such as data on credit card usage.

The core purpose of profiling is for the platforms to simply better understand their customers and develop their services. User profiles for individuals or groups allow targeting and personalisation of the offering based on user needs and preferences, and practical examples of making use of this knowledge include tailoring of services, price-discrimination, fraud detection and filtering of either services or users.

Pros and cons of profiling

From the user perspective, profiling is often discussed regarding problems that arise. Firstly, the data collected is largely from sources other than the individuals themselves, and the whole process of information gathering and processing is often a non-transparent activity. The user may thus have little or no knowledge of what is being known and recorded of them or how their user profile data is analysed. Secondly, how profiles are made use of in platforms, as well as how this data may be redistributed and sold onwards, is a concern. Discrimination may apply not only to needs-based tailoring of service offering and pricing but extend into ethically questionable decisions based on income, ethnicity, religion, age, location, the circle of friends, gender, etc. It should also be acknowledged that profiling may lead to misjudgement and faulty conclusions, and it may be impossible for the user to correct and escape such situations. The third and most serious problem area with profiling is when data and information on users is applied in harmful and malicious ways. This involves, for example, intentionally narrowing down options and exposure of the user to information or services or aggressively manipulating, shaping and influencing user behaviour. In practice this can mean filter bubbles, fake news, exclusion, political propaganda, etc. And in fact, the very idea of everything we do online or offline being recorded and corporations and governments being able to access this information can be pretty intimidating. Let alone the risk of this information being hacked and used for criminal purposes. Add advanced data analytics and artificial intelligence to the equation and the threats seem even less manageable.

However, profiling can and should rather be a virtuous cycle that allows platforms to create more relevant services and tailor personalised, or even hyper-personalised, content. This means a smooth “customer journey” with easy and timely access to whatever it is that an individual finds interesting or is in need of. Profiling may help you find compatible or interlinked products, reward you with personally tailored offers and for example allow services and pricing to be adjusted fairly to your lifestyle. In the future we’re also expecting behavioural analytics and psychological profiling to be used increasingly in anticipatory functions, for example to detect security, health or wellbeing deviations. These new application areas can be important not only for the individual but the society as a whole. Imagine fraud, terrorism or suicidal behaviours being tactfully addressed at early stages of emergence.

Where do we go from here?

Concerns raised over profiling are inducing actions in the public and private sectors respectively and in collaboration. A focal example in the topic of data management in Europe is the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) (EU) 2016/679 that will be applied in all European Union Member States from 25 May 2018 onwards. This regulation addresses the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data. And even if launched as a European rather than a global initiative, the GDPR applies to all entities processing personal data of EU citizens, and many global players have in fact already claimed compliance in all their practices. Issues covered by the regulation include limiting the scope of personal data to be collected, the individual’s right to access data on them and detailed responsibilities for those processing personal data.

While the EU tries to manage the protection of personal data and thus bring transparency and fairness to profiling, the Chinese government is exploring a very different direction by being taking the lead in gradually introducing a Social Credit System. This model is at the moment being piloted, with the aim to establish the ultimate profiling effort of citizens regarding their economic and social status. Examples of the functioning of the credit system include using the data sourced from a multitude of surveillance sources to control citizens’ access to transport, schools, jobs or even dating websites based on their score.

Another type of initiative is the Finnish undertaking to build an alternative system empowering individuals to have an active role in defining the services and conditions under which their personal information is used. The IHAN (International Human Account Network) account system for data exchange, as promoted by the Finnish Innovation Fund Sitra, is designed analogously to the IBAN (International Bank Account Number) system used in banking. The aim with IHAN is to establish an ecosystem for fair human-driven data economy, at first starting in Finland and then extending to Europe and onwards. The plan entails creating common rules and concept for information exchange, and testing of the technical platform will be done together with pilots from areas of health, transport, agriculture, etc.

Selected articles and websites

Business Insider Nordic: China has started ranking citizens with a creepy ‘social credit’ system — here’s what you can do wrong, and the embarrassing, demeaning ways they can punish you

François Chollet: What worries me about AI

General Data Protection Regulation (EU) 2016/679 – EUR-Lex

Kirk Borne: Top Data Trends for 2018 – Part 1

Platform Value Now: Tackling fake news and misinformation in platforms

Sitra: Human-driven data economy

Wikipedia: Profiling (information science)

Wikipedia: Social Credit System

Wolfie Christl, Cracked Labs: Corporate Surveillance in Everyday Life

Tackling fake news and misinformation in platforms

The online world is increasingly struggling with misinformation, such as fake news, that is spreading in digital platforms. Intentionally as well as unintentionally created and spread false content travels fast in platforms and may reach global audiences instantaneously. To pre-screen, monitor, correct or control the spreading is extremely difficult, and often the remedial response comes only in time to deal with the consequences.

In this signal post we study the problem of misinformation in the platform economy but also list potential solutions to it, with forerunner examples. Defining and establishing clear responsibilities through agreements and regulation is one part of the cure, and technological means such as blockchain, reputation systems, algorithms and AI will also be important. Another essential is to support and empower the users to be aware of the issue and practice source criticism, and this can be done for example by embedding critical thinking skills into educational curricula.

Misinformation − the size of the problem

Fake news or misinformation, in general, is not a new phenomenon, but the online world has provided the means to spread it faster and wider with ease. Individuals, organisations and governments alike can be the source or target audience of misinformation, and fake contents can be created and spread with malicious intentions, by accident or even with the objective of entertaining (for example the news satire organization The Onion).

Digital online platforms are often the place where misinformation is being released and then spread by liking, sharing, information searching, bots, etc. The online environment has not yet been able to adopt means to efficiently battle misinformation, and risks and concerns involved vary from reputation damage to global political crises. The most pessimistic views even warn us of an “infocalypse”, a reality-distorting information apocalypse. Others talk about the erosion of civility as a “negative externality”. This view points out that misinformation could, in fact, be tackled by companies in the platform economy analogously to how negative environmental externalities are tackled by manufacturing companies. It has also been suggested that misinformation is a symptom of deep-rooted systemic problems in our information ecosystem and that such an endemic condition in this complex context cannot be very easily fixed.

Solutions − truth, trust and transparency

Remedies to fake news and misinformation are being developed and implemented, even if designing control and repair measures may seem like a mission impossible. Fake accounts and materials are being removed by social media platforms, and efforts to update traditional journalism values and practices in the platform economy are being initiated. Identification and verification processes are a promising opportunity to improve trust, and blockchain among other technologies may prove pivotal in their implementation.

Example: The Council for Mass Media in Finland has recently launched a label for responsible journalism, which is intended to help the user to distinguish fake content and commercials from responsible and trustworthy journalism. The label is meant for both online and traditional media that comply with the guidelines for journalists as provided by the council.

Algorithms and technical design in general will also have an important part to play in ensuring that platforms provide the foundation and structure that repels misinformation. Taking on these responsibilities also calls for rethinking business models and strategies, as demand for transparency grows. One specific issue is the “filter bubble”, a situation where algorithms selectively isolate users to information that revolves around their viewpoint and block off differing information. Platforms such as Facebook are already adjusting and improving their algorithms and practices regarding, for example, their models for advertising.

Example: Digital media company BuzzFeed has launched an “outside your bubble” feature, which specifically gives the reader suggestions of articles providing differing perspectives compared to the piece of news they just read.

Example: YouTube is planning to address misinformation, specifically by adding “information cues” with links to third party sources when it comes to videos covering hoaxes and conspiracy theories. This way the user will automatically have suggestions to access further and possibly differing information on the topic.

Selected articles and websites

BuzzFeed: He Predicted The 2016 Fake News Crisis. Now He’s Worried About An Information Apocalypse.

BuzzFeed: Helping You See Outside Your Bubble

Engadget: Wikipedia had no idea it would become a YouTube fact checker

Financial Times: The tech effect, Every reason to think that social media users will become less engaged with the largest platforms

Julkisen sanan neuvosto: Mistä tiedät, että uutinen on totta?

London School of Economics and Political Science: Dealing with the disinformation dilemma: a new agenda for news media

Science: The science of fake news

The Conversation: Social media companies should ditch clickbait, and compete over trustworthiness

The Onion: About The Onion

Wikipedia: Fake news

Wikipedia: Filter bubble

Demographic factors in the platform economy: Age

Intuitively thinking online platforms seem to be all about empowerment, hands-on innovation and equal opportunities. In the digital world, anyone can become an entrepreneur, transform ideas into business and, on the other hand, benefit from innovations, products and services provided by others. But how accessible is the platform economy for people of different age? And how evenly are the opportunities and created value distributed? Some fear that platforms are only for the young and enabling the rich get richer while the poor get poorer.

In this signal post, we discuss age in the context of the platform economy. In future postings, we will explore other factors such as gender and educational background.

Why is this important?

When it comes to ICT (Information and Communication Technology) skills and adoption, the young typically are forerunners. For example, social media platforms were in the beginning almost exclusively populated by young adults. But studies show that older generations do follow, and at the moment there is little difference in the percentage of adults in their twenties or thirties using social media in the US. And those in their fifties are not too far behind either!

Along with the megatrend of aging, it makes sense that not only the young but also the middle-aged and above are taking an active part in the platform economy. Some platform companies already acknowledge this, and tailored offering and campaigns to attract older generations have been launched for example in the US. In Australia, the growing number of baby boomers and pre-retirees in the sharing economy platforms, such as online marketplaces and ride-sourcing, has been notable. Explanatory factors include the fact that regulation and transparency around platform business have matured and sense of trust has been boosted.

One peculiar thing to be taken into account is that many platforms actually benefit from attracting diverse user segments, also in terms of age. This shows especially in peer-to-peer sharing platforms. The user population of a platform is typically heavy with millennials, who are less likely to own expensive assets such as cars or real estate. Instead, their values and financial situations favour access to ownership. But the peer-to-peer economy cannot function with only demand, so also supply is needed. It is often the older population that owns the sought-after assets, and they are growingly willing to join sharing platforms. Fascinating statistics are available, for example, of Uber. As much as 65% of Uber users are aged under 35, and less than 10% have passed their 45th birthday. The demographics of Uber drivers tell a different story: adults in their thirties cover no more than 30%, and those aged 40 or more represent half of all drivers. In a nutshell, this means that the older generation provides the service and their offspring uses it.

Things to keep an eye on

In the future, we expect to see more statistics and analysis on user and producer populations of different types of platforms. These will show what demographic segments are attracted by which applications of the platform economy as well as which age groups are possibly missing. The information will help platforms to improve and develop but also address distortion, hindrances and barriers.

It may also be of interest to the public sector to design stronger measures in support of promoting productive and fair participation in the platform economy for people of all ages. Clear and straightforward regulation and other frameworks will be important to build trust and establish common rules.

Selected articles and websites

GlobalWebIndex: The Demographics of Uber’s US Users

Growthology: Millennials and the Platform Economy

Harvard Business Review: The On-Demand Economy Is Growing, and Not Just for the Young and Wealthy

INTHEBLACK: The surprising demographic capitalising on the sharing economy

Pew Research Center: Social Media Fact Sheet

Pipes to platforms: How Digital Platforms Increase Inequality

Uber: The Driver Roadmap

Social connectivity in platforms

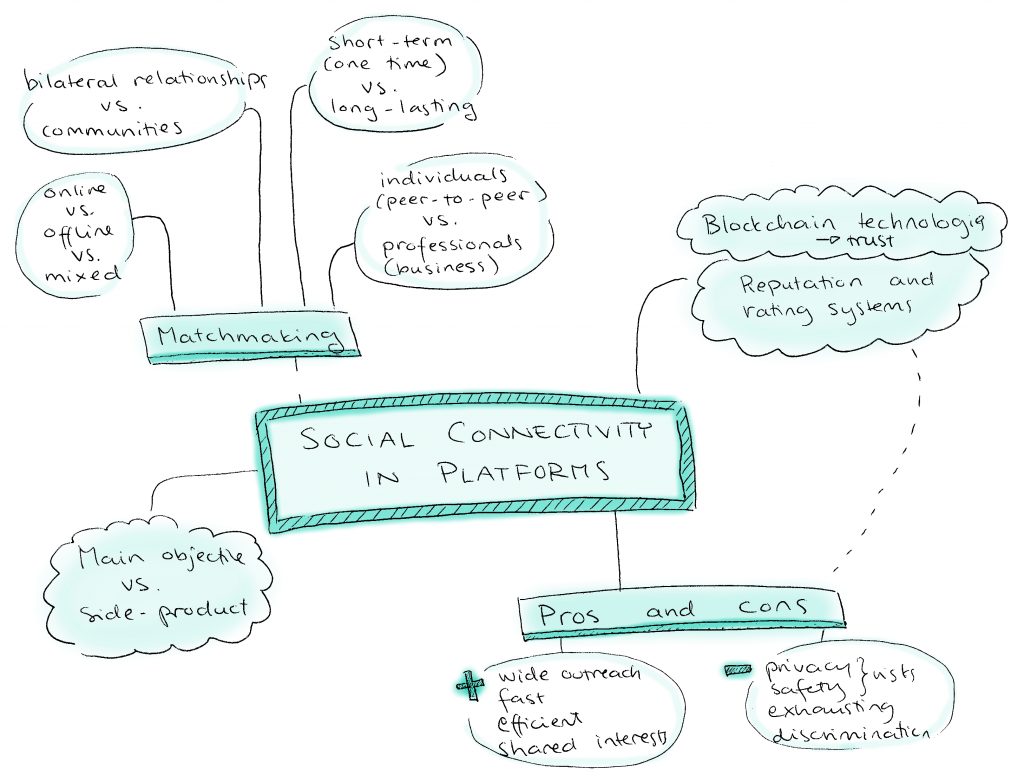

Platforms are all about enabling connections to form between actors, typically producers and users of any given tangible or intangible commodity. But to what extent do these connections result in social value for individuals? There are of course social media platforms that by definition focus on maintaining or creating human relationships whether based on family ties, existing friendships, professional networking, dating or shared hobbies or interests. Interaction, communication and social ties nevertheless take place in other platforms too, and the positive and negative impacts of these may come as a rather unexpected side effect to the platform owner as well as users.

For example, ride-sourcing and hospitality platforms are virtual matchmakers, whose work comes to fruition when the virtual connection proceeds to a face-to-face meeting. A ride is then being shared with or a home is being rented to someone who only a little while back was a stranger. Many suchlike relationships remain one-time transactions, but they can also grow to regular exchanges over the platform or profound relationships outside the platform. Connectivity is as much a part of peer-to-peer platforms as professional and work-related platforms. You may form a personal connection with a specific IT specialist over the IT support system platform even if you never met them offline. Or supply chain business partnerships may evolve out of a one-time task brokerage platform transaction.

Why is this important?

The benefits of platform economy regarding social connectivity are the wide outreach and extremely fast and efficient matchmaking based on personal, professional of other mutual interests. In spite of complex technologies and big data flows, these social connections on platforms can be truly personalised, intimate and rewarding. The flipside of the coin is risks around privacy, safety and security. Reputation, review and rating systems are important ways to tackle these and could help to strengthen the sense of trust and community across user populations of platforms. In fact, one interesting finding of social connectivity in platforms is that relationships are maintained and formed bilaterally between the individual as well as among groups, communities and actor ecosystems. Short-term or long-lasting, these relationships often mix online and offline realities.

Additional concerns related to social connectivity in platforms is how much they eventually promote equality and fairness or if the social interaction is more of a burden than a benefit. Reputation and rating systems may result in unfair outcomes, and it may be difficult for entrants to join in a well-established platform community. Prejudices and discrimination exist in online platforms too, and a platform may be prone to conflict if it attracts a very mixed user population. In the ideal case, this works well, e.g. those affluent enough to attain property and purchase expensive vehicles are matched with those needing temporary housing or a ride. But in a more alarming case, a task-brokerage platform may become partial to assigning jobs based on criteria irrelevant to performance, e.g. based on socio-economic background. Platforms can additionally have a stressful impact on individuals if relationships formed are but an exhaustingly numberous short-term consumable.

Emerging technologies linked to platforms are expected to bring a new flavour to social aspects of the online world. The hype around blockchain, for example, holds potential to enhance and ease social connectivity when transactions become more traceable, fair and trustworthy. It has even been claimed that blockchain may be the game changer regarding a social trend to prioritise transparency over anonymity. Blockchain could contribute to individuals and organisations as users becoming increasingly accountable and responsible for any actions they take.

Things to keep an eye on

Besides technology developers and service designers’ efforts to create socially rewarding yet safe platforms, a lot also happens in the public sector. For example, European data protection regulation is being introduced, and the EU policy-making anticipates actions for governance institutions to mobilise in response to the emergence of blockchain technology.

An interesting initiative is also the Chinese authorities’ plan for a centralised, governmental social credit system that would gather data collected from individuals to calculate a credit score that could use in any context such as loans applications or school admissions. By contrast, the US has laws that are specifically aimed to prevent such a system, although similar small-scale endeavours by private companies do to some extent already exist.

Selected articles and websites

Investopedia: What Is a Social Credit Score and How Can it Be Used?

General Data Protection Regulation (EU) 2016/679 – EUR-Lex

European Parliament: What if blockchain changed social values?

European Parliament: How blockchain technology could change our lives

Rahaf Harfoush: Tribes, Flocks, and Single Servings — The Evolution of Digital Behavior

Koen Frenken, Juliet Schor (2017): Putting the sharing economy into perspective, Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions

Paolo Parigi, Bogdan State (2014): Disenchanting the World: The Impact of Technology on Relationships

Persuasive computing

In the aftermath of the US election, the power of social media filter bubbles and echo chambers has again evoked discussion and concern. How much can algorithms influence our behaviour?

Why is this important?

Data is a key part of the functioning of any platform, and analysis and filtering of data streams allows, for example, tailoring of the platform’s offering based on user data. This is evident in content platforms such as Facebook or Youtube, which learn from your behaviour and customise the user view and suggested contents accordingly. This filtering for personalised experience is valuable and helps the user navigate in their areas of interests, but there are also various drawbacks. Filtering and especially its invisibility can cause ‘filter bubbles’, where the user experience is threatened to limit to information that reinforces existing beliefs. This leads to polarization. What is even more troubling is that the algorithms can be tweaked to manipulate the feelings of users, according to a 2014 study done by Facebook without the users knowing.

Things to keep an eye on

The debate is now on-going as to how much algorithms can affect our actions. Some claim that the analysis and manipulation of social media feeds was instrumental in the US elections, while some say that the claims are overrated and the hype mostly benefits the analytics companies. In any case, the filtering of data is not inconsequential and there are increasing calls for more transparency to the filtering algorithms as well as for the ownership of the behavioural data collected through platforms. In part this issue becomes more and more topical with the advances in artificial intelligence, which makes data analysis more sophisticated and accessible. There are also interesting experiments – often with artistic goals – in confusing the algorithms in order to make the data they collect unusable by the platform owner.

Selected articles and websites

Will Democracy Survive Big Data and Artificial Intelligence?

The Rise of the Weaponized AI Propaganda Machine

The Truth About The Trump Data Team That People Are Freaking Out About

Robert Mercer: the big data billionaire waging war on mainstream media

How to hide your true feelings from Facebook

Persuading Algorithms with an AI Nudge

Distributed autonomous organization

A distributed (or decentralised) autonomous organisation (DAO) is a new form of organising business transactions, one in which all agreements and transactions are done through code and saved in a shared ledger. It is enabled by blockchain and smart contracts. In a DAO there is no management, but instead complete transparency (as all the transactions are shared) and total shareholder control (as anyone that takes part in a DAO can decide what to do with the funds invested). More broadly, a DAO is an experiment of organising business transactions, where trust is outsourced to code and blockchain. The prominent example of a DAO is aptly named “The DAO”, which is an investment fund without management.

Why is this important?

DAO is a structure built upon a blockchain platform such as Ethereum. It is itself also a type of platform in that through it many types of transactions can be done. DAO is an example of how platforms do not just transfer old ways of organising to digital, networked world, but instead enable new forms of organising and governance. DAO is a structure on which to build different types of activities from investment funds to shared data repositories. It can be used to organise an autonomous ridesharing ecosystem, where there are competing applications for matching, payment, user interface etc, all working seamlessly together. It enables new governance models, such as “futarchy”, which uses a prediction market to choose between policies.

DAO can also be seen as a response to the transformation in work, much like platform cooperativism. As work becomes more like a risky investment than a steady source of income, organisational structures can help cope with the new reality. Whereas platform cooperatives solve the problem by using digital platform to enable fair distribution of value and power, DAOs try to achieve the same through smart contracts, code and blockchain – in other words without humans who could risk the fairness of the system.

Things to keep an eye on

DAOs are based on the idea that all rules can be embedded in the code and system. Smart contracts are described as plain English, but what matters really is the code that defines what the contracts do. Code is susceptible to human error, which means that those agreeing on the conditions of the contract must be able to decipher the code or trust that someone has checked it. An interesting example of what this can lead to happened last spring in The DAO.

In June 2016 a hacker managed to use a vulnerability in a smart contract and transfer a large amount of funds to another contract within the DAO. This led to an ideological discussion about what to do: should this transaction be cancelled and the immutability of the blockchain thus questioned, or should those who lost their money just accept what happened. Because there is no one officially in control, the developers of the Ethereum platform, on which The DAO operates, recommended as their preferred solution “hard fork”, i.e. to cancel the transaction and gave the decision to participants of The DAO. A majority voted in favour of the hard fork, but the original version of the blockchain containing the disputed transaction still exists as “Ethereum Classic”.

The example above indicates how the practices around DAOs are developing. Blockchain technology is still in its infancy and lots of failures and experimentation on the applications are to be expected. There is now clearly a need for built-in governance systems for dispute settlement. One example of this is Microsoft’s project Bletchley, which aims to develop a distributed ledger marketplace and “cryptlets” that would work in the interface between humans and the blockchain implementations. Cryplets would basically mix more traditional methods to ensure trust with blockchain.

On a broader level there is the question of whether or not a DAO is an organisation and what is its legal status or the role of the tokens that represent funds or other assets. There is also the question of whether there is really a need for such an organisation, which eliminates middlemen completely, as middlemen can be useful and provide services other than just matching demand and supply. On a technological and more long-term note, as the blockchain is based on encryption, it is vulnerable to quantum computers, which could break the encryption by calculating private keys from public keys in minutes.

Selected articles and websites

Post-blockchain smart contracts creating a new firm

TED Talk: How the blockchain will radically transform the economy | Bettina Warburg

The humans who dream of companies that won’t need them

The Tao of “The DAO” or: How the autonomous corporation is already here

The DAO: a radical experiment that could be the future of decentralised governance

Why Ethereum’s Hard Fork Will Cause Problems in the Coming Year

The gateway to a new business order: Why crowdfunding is just the start of the next era of organisations

Social impacts of the platform economy

Platforms create value well beyond economic profits, and the topic of social and societal impacts resulting from the emerging platform economy has been getting more and more attention lately. Platform economy undoubtedly has both positive and negative impacts on individuals and families as well as wider communities and entire societies. However, the range and depth of these impacts can only be speculated, as only very early evidence and research on the topic has been produced. After all, the platform economy is only in its infancy.

Why is this important?

Platforms have potential to address major societal challenges such as those connected to health, transport, demographics, resource efficiency and security. They could massively improve our individual daily lives as well as contribute to equal opportunities and progress in developing economies. On the other hand, platform economy can result in negative impacts in the form of disruptions and new threats. Privacy and safety concerns have deservedly been acknowledged, and other possible risks include those related to social exclusion, discrimination and the ability of policies and regulations to manage with whatever platform economy may bring about.

Some examples of positive and negative social impact categories of the platform economy include the following, which may distribute equally, create further division or bridge the gap among various social segments:

- employment and unemployment

- livelihood and wealth

- education and training

- skills, knowledge and competences

- health and physical wellbeing

- mental health and wellbeing

- privacy, safety and security

- social inclusion or exclusion, access to services, etc.

- new social ties and networks, social mixing

- social interaction and communication: families, communities, etc.

- behaviour and daily routines

- living, accommodation and habitat

- personal identity and empowerment

- equality, equity and equal opportunities or discrimination

- citizen participation, democracy

- sufficiency or lack of political and regulatory frameworks.

Platforms may have very different impacts on different social groups, for example, based on age, gender, religion, ethnicity and nationality. Socioeconomic status, i.e. income, education and occupation, may also play an important role in determining what the impacts are, although it is also possible that platform economy balances out the significance of suchlike factors. One important aspect requiring special attention is how to make sure that vulnerable groups, such as the elderly or those with disabilities or suffering from poverty, can be included to benefit from the platform economy.

Things to keep an eye on

Value captured and created by platforms is at the core of our Platform Value Now (PVN) project, and there are several other on-going research strands addressing social and societal impacts of the platform economy. One key topic will be to analyse and assess impacts of the already established platform companies and initiatives, which necessitates opening the data for research purposes. To better understand the impacts and how they may develop as platform economy matures is of upmost importance to support positive progress and to enable steering, governance and regulatory measures to prevent and mitigate negative impacts.

Selected articles and websites

Koen Frenken, Juliet Schor, Putting the sharing economy into perspective, Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, (2017)

The Rise of the Platform Economy

Uber and the economic impact of sharing economy platforms

VTT Blog: Openness is the key to the platform economy

SUSY project: Solidarity economy