The platform economy is much more than business giants Uber, Amazon or Google. Platforms can facilitate a transformation in ways of organising work, value creation, sharing, and resources. While the currently dominant development direction tends to favour large platform companies with monopoly statuses, alternative undercurrents can be identified.

Why is this important?

The focus in the platform economy has largely been on how it enables new ways to create value. Value comes from both users and producers while the platform adds its value to the ecosystem by providing tools for matching and curating the content. Network effects further multiply the value based on the extensiveness of the network.

The sole focus on value creation has, however, lead to ignoring the mechanisms by which value is distributed in the network. Platforms both mediate value creation and add value through connecting actors, sharing resources, and integrating systems, but the question is, how is this value shared? Especially platforms with near monopoly status tend to aggregate much of the value to the platform itself and not share it back to the users of the platforms in a fair amount. Platform companies, like other companies, give the surplus to their shareholders. In some cases, it could even be said that platforms exploit their users by treating them as workforce without benefits or as sources of data to be sold to advertisers. At the same time, little attention is put into how platforms serve society. The discussion is more about how they disrupt existing industries and navigate in the gray areas of legislation.

Three approaches challenging the dominant platform business

Although the big platform companies produce most of the headlines, there are interesting initiatives for alternative forms of platform economy. One is the revitalisation of the idea of commons. In the context of platforms and peer-to-peer economy, commons is understood as a mode of societal organisation, along with market and the state, and combines a resource with a community and a set of protocols. A key question related to platform economy is what data, tools or infrastructure should be treated as commons, how to govern them and how to build both for-profit and non-profit services on top of them. These and other questions of a “commons economy” are being experimented with in peer-to-peer initiatives, platform cooperatives, and blockchain-based distributed autonomous organizations.

In the same way that commons challenges the notion of ownership, a growing number of companies called “Zebras” are challenging the notion of growth. “Zebras” are companies that aim for a sustainable prosperity instead of maximal growth like “Unicorns”. They can still be for-profit but also do social good. An interesting question is whether platform economy can be used to transform the current growth-based economic system towards a more sustainable version, or will the “Zebras” as well as cooperatives and commons be left to the margins in the dominance of platform monopolies.

A third interesting idea utilising the new possibilities of connecting and collaborating through digital platforms is the idea of team economy by GoCo. It challenges the idea of a permanent organisation. In team economy, groups form around an issue or a problem and disperse once the work is done. In contrast to gig economy, the tasks aren’t simplified or clearly defined, but rather what needs to be done is jointly explored with the customer. A platform is needed to connect and offer a collaborative workplace but also provides a record of everything a person has done, a sort of online CV for the platform age.

It remains to be seen to what extent commons, “zebras” and team economy can influence the development of platform economy, but they are interesting ideas to keep an eye on.

Selected articles and websites

- ETUI Policy Brief: The emergence of peer production

- Transnational Institute: Commons Transition and P2P

- Hinesight: Commons or commodities?

- Medium: Zebras Fix What Unicorns Break

- GoCo

Problems with blockchain

A lot of hopes are placed on blockchain technology. They range from more modest aspirations, like ensuring secure food chains, to hyperbolic claims of creating economic and socio-political emancipation of humankind. Blockchain is said to offer a decentralised way of doing things while solving the problem of trust, which makes it very appealing for platform economy. What is often left out is the consideration of the negative consequences and the barriers to the wide adoption of the blockchain.

Negative consequences and barriers

The main negative impact on current implementations of blockchain relates to energy usage and consequential environmental and other impacts. Blockchains require a lot of computing power, which in turn requires a lot of electricity and cooling power. For example, for Bitcoin alone it has been calculated that by 2020 it might use as much energy as Denmark. While blockchain-based solutions – or cryptogovernance in general – has been offered as a way to alleviate some environmental problems by increasing traceability and ensuring ownership, the negative impact of these solutions to the environment should not be ignored.

The current architecture of the blockchain is high on energy consumption, and also has problems with scaling. The root problem is that all transactions in the blockchain have to be processed by basically everyone and everyone must have a copy of the global ledger. As the blockchain grows, more and more computing power and bandwidth are required and there is a risk of centralisation of decision making and validation power in the blockchain as only a few want to devote their efforts to keeping the blockchain running.

Along with problems of scaling, the issue of governance in blockchains is an unsolved challenge. Since there is no central actor, there needs to be mechanisms for solving disputes. The forking of The DAO and the discussions around it are a case in point. So while blockchain may offer new decentralised solutions to governance, the technology in itself is not enough.

Possible solutions

There are some solutions to the problem of scaling, such as increasing block size, sharding (breaking the global ledger into smaller pieces) and moving from proof of work consensus mechanism to proof of stake. One interesting solution that also decreases the computational power needed is Holochain. Instead of having a global ledger of transactions, in a holochain everyone has their own “blockchain”, and only the information needed to validate the chains is shared. This means basically that while a blockchain validates transactions with global consensus, a holochain validates people – or to be more precise, the authenticity of the chains of transactions people own.

Whatever the technological solution, a discussion on the negative consequences of blockchain is required to balance the hype. Do we want to implement blockchains everywhere no matter the environmental costs? What are the tradeoffs we are willing to make?

Selected articles and websites

- Hackernoon: Blockchains don’t scale

- Motherboard: Bitcoin could consume as much electricity as Denmark by 2020

- Coindesk: Blockchain’s 4 biggest assumptions

- Cointelegraph: Why blockchain alone cannot fix the privacy issue

- Cryptocoinnews: Blockchains will enhance the economic and socio-political emancipation of humankind

- Nature: The environment needs cryptogovernance

- Ensia: What can blockchain do for the environment?

- Ceptr: Holochain

Demographic factors in the platform economy: Gender

Often it may feel like we are all anonymous and equal in the online world, but at other times age, gender and other demographic and socio-economic factors seem to matter greatly. In this signal post, we discuss gender in the context of the platform economy. (See also previous post focussing on age.) What is the gender balance among platform users? Who designs and programs platforms? And what is the role of user behaviour and online culture?

Why is this important?

Platform economy has potential to support societal integrity by providing an abundance of opportunities to women and men alike. For example, gig work enabled by digital platforms brings flexibility regarding working hours and location, which is assumed to benefit stay-at home parents, who under other circumstances would stay outside the workforce.

Zooming into platform user populations, in social media usage, Uber passengers and consumers of the on-demand economy there has been found little or no difference in the US in the numbers of women and men. Sounds good! However, if we look at Uber drivers, as much as 86% are male. The exact opposite situation is found with a marketplace for handmade and vintage goods Etsy, where out of the 1.5 million sellers 86% are female. Could it be that platforms reflect and replicate the existing biases and traditions when it comes to the division of labour between women and men?

Another central point of interest is for whom platforms are designed. And who designs them? The inherent male-dominance in the software industry and venture capital is reflected in platforms in that it is dominantly men who design and make decisions about how platforms function. A characteristic example of challenges in this area is the recent controversy over a Google employee manifesto, which shows that despite efforts to increase diversity, old attitudes are very much alive.

An equally important question is how people behave and treat one another when using platforms. A case in point is the numerous incidents of online harassment and doxing (e.g. maliciously gathering and releasing private information about a person). One alarming example from video game culture gone astray is the Gamergate controversy. Online culture also shows in reputation and rating systems, where disclosing of background information such as gender may influence behaviour unfairly.

Things to keep an eye on

For new as well as existing platforms, the topic of gender is an important aspect of consideration in platform design. User strategies can at best pinpoint specific gender-related needs and provide targeted and tailored solutions. Platform owners should also acknowledge the responsibility and equality points of view to ensure the platform welcomes all unique users and treats them on an equal footing. Underlying algorithms as well as the culture of the user population should support equal opportunities and broadmindedness.

Also, it will be increasingly important for governments to keep gender equality in view when promoting digitalisation agendas, especially to involve women. Nations do face different types of challenges based on cultural context and nuances as well as status in financial and technological development, and some recommendations on how to harness women’s potential are given in a recent study.

Selected articles and websites

Harvard Business Review: The On-Demand Economy Is Growing, and Not Just for the Young and Wealthy

Pipes to platforms: How Digital Platforms Increase Inequality

GlobalWebIndex: The Demographics of Uber’s US Users

Uber: The Driver Roadmap

Pew Research Center: Social Media Fact Sheet

Pew Research Center: Online Harassment 2017

Poutanen & Kovalainen (2017): New Economy, Platform Economy and Gender

CNNtech: Storm at Google over engineer’s anti-diversity manifesto

Watanabe et al. (2017): ICT-driven disruptive innovation nurtures un-captured GDP – Harnessing women’s potential as untapped resources

Wikipedia: Gamergate controversy

European Parliament, Think Tank: The Situation of Workers in the Collaborative Economy

openDemocracy: Back to the future: women’s work and the gig economy

Demographic factors in the platform economy: Age

Intuitively thinking online platforms seem to be all about empowerment, hands-on innovation and equal opportunities. In the digital world, anyone can become an entrepreneur, transform ideas into business and, on the other hand, benefit from innovations, products and services provided by others. But how accessible is the platform economy for people of different age? And how evenly are the opportunities and created value distributed? Some fear that platforms are only for the young and enabling the rich get richer while the poor get poorer.

In this signal post, we discuss age in the context of the platform economy. In future postings, we will explore other factors such as gender and educational background.

Why is this important?

When it comes to ICT (Information and Communication Technology) skills and adoption, the young typically are forerunners. For example, social media platforms were in the beginning almost exclusively populated by young adults. But studies show that older generations do follow, and at the moment there is little difference in the percentage of adults in their twenties or thirties using social media in the US. And those in their fifties are not too far behind either!

Along with the megatrend of aging, it makes sense that not only the young but also the middle-aged and above are taking an active part in the platform economy. Some platform companies already acknowledge this, and tailored offering and campaigns to attract older generations have been launched for example in the US. In Australia, the growing number of baby boomers and pre-retirees in the sharing economy platforms, such as online marketplaces and ride-sourcing, has been notable. Explanatory factors include the fact that regulation and transparency around platform business have matured and sense of trust has been boosted.

One peculiar thing to be taken into account is that many platforms actually benefit from attracting diverse user segments, also in terms of age. This shows especially in peer-to-peer sharing platforms. The user population of a platform is typically heavy with millennials, who are less likely to own expensive assets such as cars or real estate. Instead, their values and financial situations favour access to ownership. But the peer-to-peer economy cannot function with only demand, so also supply is needed. It is often the older population that owns the sought-after assets, and they are growingly willing to join sharing platforms. Fascinating statistics are available, for example, of Uber. As much as 65% of Uber users are aged under 35, and less than 10% have passed their 45th birthday. The demographics of Uber drivers tell a different story: adults in their thirties cover no more than 30%, and those aged 40 or more represent half of all drivers. In a nutshell, this means that the older generation provides the service and their offspring uses it.

Things to keep an eye on

In the future, we expect to see more statistics and analysis on user and producer populations of different types of platforms. These will show what demographic segments are attracted by which applications of the platform economy as well as which age groups are possibly missing. The information will help platforms to improve and develop but also address distortion, hindrances and barriers.

It may also be of interest to the public sector to design stronger measures in support of promoting productive and fair participation in the platform economy for people of all ages. Clear and straightforward regulation and other frameworks will be important to build trust and establish common rules.

Selected articles and websites

GlobalWebIndex: The Demographics of Uber’s US Users

Growthology: Millennials and the Platform Economy

Harvard Business Review: The On-Demand Economy Is Growing, and Not Just for the Young and Wealthy

INTHEBLACK: The surprising demographic capitalising on the sharing economy

Pew Research Center: Social Media Fact Sheet

Pipes to platforms: How Digital Platforms Increase Inequality

Uber: The Driver Roadmap

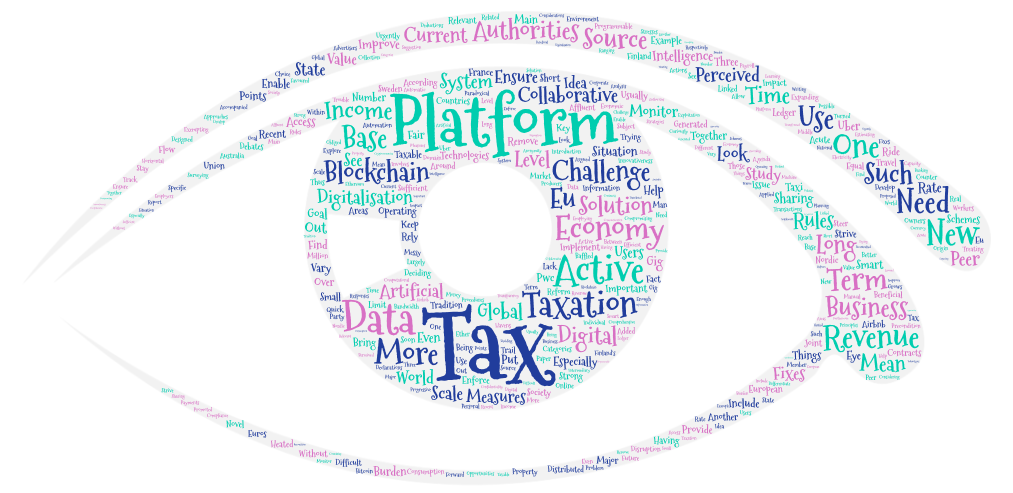

Platforms and blockchain to bring on beneficial disruption to taxation

Digitalisation and platform economy are usually perceived as a challenge to taxation as it is difficult to monitor and enforce taxation in the digital and global economy. New rules are needed for deciding which activities are taxable and which are not in the in sharing, collaborative and platform economies. A recent US study points out that platform businesses such as Uber and Airbnb have an impact on all three of the major categories of revenue sources: consumption taxes, income taxes and property taxes. The situation is especially relevant for Nordic countries, where the tradition of a strong tax base has been the precondition for an affluent society. The main goal is to develop taxation so that the platform economy can strive while ensuring sufficient tax revenue without compromising innovativeness.

The platform economy could, however, be the solution to these new challenges. If we have a more comprehensive look at taxation, expanding from acute challenges to long-term system-level opportunities, platforms together with blockchain and artificial intelligence technologies could help reform and improve taxation systems.

Why is this important?

Tax authorities around the world are urgently trying to find short-term and long-term fixes to the challenges linked to digitalisation and platforms. The sharing economy is one of the areas, where heated debates have accompanied the introduction of new tax measures (see e.g. Finland, France, Sweden, the US or Australia). Approaches vary from exempting small-scale peer-to-peer activities from taxes to treating gig workers as business owners or considering ride-sourcing equal to taxi travel. The importance of the issue is put into the scale in a study by PwC, estimating the value of transactions in Finland’s collaborative market in 2016 to over 100 million euros.

The European Union (EU) has been active in surveying tax challenges in the digital economy and collaborative economy. Counter measures are being designed and implemented by the Member States respectively, but joint actions and strategies on a European level and globally are also needed to ensure fair operating environment. The EU agenda stresses that all economic operators, including those in collaborative economy, are subject to taxation either according to personal income, corporate income or value added tax rules.

While the authorities are baffled, so are the individual users and producers of platforms. We are currently in a paradoxical situation, where online platforms rely on digitalisation and automation, yet the related tax procedures, deductions and declarations are largely a manual and messy burden.

Things to keep an eye on

The responses from tax authorities do not, and should not, limit to quick fixes within current tax schemes but also explore long-term considerations on principles of taxation and novel means to implement them. Examples of progressive ideas include the suggestion of a specific tax on digital economy and taxation of platforms based on bandwidth or other activity measures such as number of users, flow of data, computational capacity, electricity use or number of advertisers. It has also been proposed that tax rates should differentiate according to the origin of revenues to better steer platform-based business: a different tax burden for revenues generated by one-time access and another tax rate for revenues generated by data exploitation.

Curiously enough, the challenge could be turned into the solution, as the platform economy especially together with blockchain and artificial intelligence technologies could provide the means to more efficient future schemes of taxation. One key problem is that information of and data from platforms does not reach tax authorities. By employing blockchain and distributed ledger it would be possible to remove the need for any intermediary and improve transparency and confidentiality. For example, blockchain applied to payroll would enable removal of businesses as a middle man and allow automatic tax collection using smart contracts. And having data in distributed ledgers would enable analysis of that data for monitoring of tax compliance and horizontal communication between authorities among other things. In fact, blockchain has been argued to provide solutions from digitalisation challenges ranging from anonymity and lack of paper trail to tax havens.

Another forward-looking idea to taxation from the world programmable economy domain involves smart contracts, cryptocurrencies and programmable money, such as Bitcoin or ether by Ethereum. These are currently perceived as a source of trouble to tax authorities, but what if they were soon to be the favoured choice and solution promoted by the state as an active party? This would mean tax authorities having access to the information on payments, on which employers would be obliged to report. Authorities could thus stay on-track in real-time even when the banking and currency system grows more and more decentralised. Furthermore, even national tax planning and writing could be transformed using artificial intelligence and machine learning in time.

Selected articles and websites

Australian Taxation office: Providing taxi travel services through ride-sourcing and your tax obligations

Australian Taxation office: The sharing economy and tax

EUobserver: Nordic tax collectors set sights on new economy

European Commission: A European agenda for the collaborative economy and supporting analysis

European Parliament: Tax Challenges in the Digital Economy

France Stratégie: Taxation and the digital economy: A survey of theoretical models

IBM: Blockchain: Tackling Tax Evasion in a Digital Economy

Institute on Taxation & Economic Policy (ITEP): Taxes and the On-Demand Economy

Kathleen Delaney Thomas, University of North Carolina Law School: Taxing the Gig Economy

OECD: Addressing the Tax Challenges of the Digital Economy

PWC: How blockchain technology could improve the tax system

Sitra: Digitalisation and the future of taxation

Sky Republic: Automating & Assuring Trust Using Enterprise Blockchain in the Era of the Programmable Economy

Skatteverket: Delningsekonomi – Kartläggning och analys av delningsekonomins påverkan på skattesystemet

TEM: Jakamistalous Suomessa 2016 – Nykytila ja kasvunäkymät (Collaborative Economy in Finland –Current State and Outlook)

The Financial: Artificial Intelligence to transform tax world

Verohallinto: Jakamistalous

Wikipedia: Bitcoin

Wikipedia: Ethereum

WU & NET Team: Blockchain: Taxation and Regulatory Challenges and Opportunities, Background note

Platforms and forestry

Platform economy brings along new opportunities for forestry, ranging from more efficient management to new data-driven services and enhancing of industrial ecology. Increases in the amount and accessibility of forest data as well as data on the raw material cycles enable new solutions and collaborations and invites novel cross-sectoral innovations. Combined with advances in material technology, forests are set to become a key component in the emerging circular economy.

Why is this mportant?

There are three main areas of impact platforms can have in the forestry sector. The first is the gathering, analysis and use of forest data. Digital platforms provide an easy access to forest data. Globally this is linked especially to monitoring forest growth and identifying illegal logging. In Finland the use cases have more to do with increased efficiency of forest management, transparent sales and new services based on data.

The second area of impact is the control of the flow of materials, including wood, cellulose and further refined products. Recycling and end-of-life management also come into the picture. Wood and particularly cellulose, and their recycled fractions, can be the (raw) material for a wide range of products from packaging and clothes to fuels and energy. However, this requires good data on the characteristics of material flows and the efficient coordination of these flows. Here a platform-based system and operation model can be helpful.

The third area of impact is increased collaboration between different actors. A traditional approach is to center the activities around a specific place or plant, and there are signs of a new wave of such industrial ecology platforms, such as the Äänekoski bioproduct mill. What is especially interesting from the point of view of platform economy are the more data-driven and virtual collaborations.

Things to keep an eye on

Having good and reliable data on forests as well as the flow of wood-based materials is essential. Therefore it is worth following how the Finnish law concerning forest data proceeds, as well as what kind of players exist in the forest data business. For example, the US company Trimble acquired two Finnish companies, Silvadata and Savcor, in 2017. Furthermore, as an increasing number of new cellulose-based materials enter the market, it is good to look at the bigger picture of material flows and collaboration between actors.

Selected articles and websites

Bittejä ja biomassaa – Tiekartta digitalisaation vauhdittamaan biotalouteen

Design Driven Value Chains in the World of Cellulose dWoC

Trimble Connected Forest

Infinited Fiber brings radical change to the textile industry

Forest Solutions Platform

Global Forest Watch

The Äänekoski bioproduct mill – a new chapter in the Finnish forest industry

Trimble doubles down on Finnish companies

Finnish plastic replacement raises EUR 1 million

Metsätietolain muuttaminen

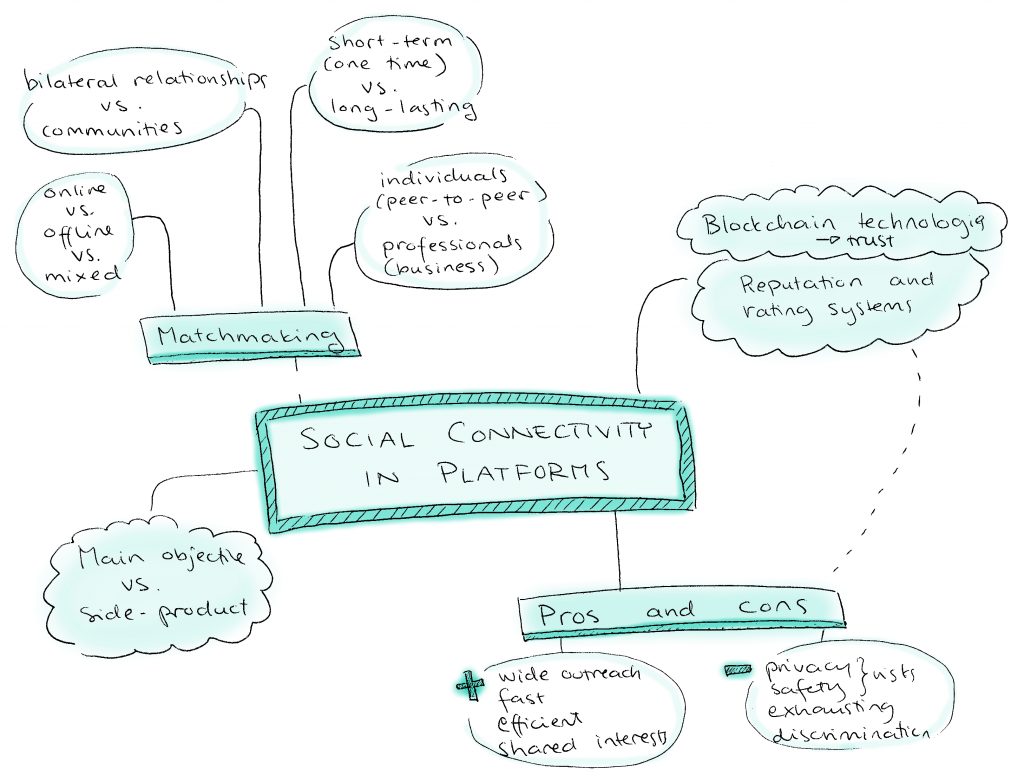

Social connectivity in platforms

Platforms are all about enabling connections to form between actors, typically producers and users of any given tangible or intangible commodity. But to what extent do these connections result in social value for individuals? There are of course social media platforms that by definition focus on maintaining or creating human relationships whether based on family ties, existing friendships, professional networking, dating or shared hobbies or interests. Interaction, communication and social ties nevertheless take place in other platforms too, and the positive and negative impacts of these may come as a rather unexpected side effect to the platform owner as well as users.

For example, ride-sourcing and hospitality platforms are virtual matchmakers, whose work comes to fruition when the virtual connection proceeds to a face-to-face meeting. A ride is then being shared with or a home is being rented to someone who only a little while back was a stranger. Many suchlike relationships remain one-time transactions, but they can also grow to regular exchanges over the platform or profound relationships outside the platform. Connectivity is as much a part of peer-to-peer platforms as professional and work-related platforms. You may form a personal connection with a specific IT specialist over the IT support system platform even if you never met them offline. Or supply chain business partnerships may evolve out of a one-time task brokerage platform transaction.

Why is this important?

The benefits of platform economy regarding social connectivity are the wide outreach and extremely fast and efficient matchmaking based on personal, professional of other mutual interests. In spite of complex technologies and big data flows, these social connections on platforms can be truly personalised, intimate and rewarding. The flipside of the coin is risks around privacy, safety and security. Reputation, review and rating systems are important ways to tackle these and could help to strengthen the sense of trust and community across user populations of platforms. In fact, one interesting finding of social connectivity in platforms is that relationships are maintained and formed bilaterally between the individual as well as among groups, communities and actor ecosystems. Short-term or long-lasting, these relationships often mix online and offline realities.

Additional concerns related to social connectivity in platforms is how much they eventually promote equality and fairness or if the social interaction is more of a burden than a benefit. Reputation and rating systems may result in unfair outcomes, and it may be difficult for entrants to join in a well-established platform community. Prejudices and discrimination exist in online platforms too, and a platform may be prone to conflict if it attracts a very mixed user population. In the ideal case, this works well, e.g. those affluent enough to attain property and purchase expensive vehicles are matched with those needing temporary housing or a ride. But in a more alarming case, a task-brokerage platform may become partial to assigning jobs based on criteria irrelevant to performance, e.g. based on socio-economic background. Platforms can additionally have a stressful impact on individuals if relationships formed are but an exhaustingly numberous short-term consumable.

Emerging technologies linked to platforms are expected to bring a new flavour to social aspects of the online world. The hype around blockchain, for example, holds potential to enhance and ease social connectivity when transactions become more traceable, fair and trustworthy. It has even been claimed that blockchain may be the game changer regarding a social trend to prioritise transparency over anonymity. Blockchain could contribute to individuals and organisations as users becoming increasingly accountable and responsible for any actions they take.

Things to keep an eye on

Besides technology developers and service designers’ efforts to create socially rewarding yet safe platforms, a lot also happens in the public sector. For example, European data protection regulation is being introduced, and the EU policy-making anticipates actions for governance institutions to mobilise in response to the emergence of blockchain technology.

An interesting initiative is also the Chinese authorities’ plan for a centralised, governmental social credit system that would gather data collected from individuals to calculate a credit score that could use in any context such as loans applications or school admissions. By contrast, the US has laws that are specifically aimed to prevent such a system, although similar small-scale endeavours by private companies do to some extent already exist.

Selected articles and websites

Investopedia: What Is a Social Credit Score and How Can it Be Used?

General Data Protection Regulation (EU) 2016/679 – EUR-Lex

European Parliament: What if blockchain changed social values?

European Parliament: How blockchain technology could change our lives

Rahaf Harfoush: Tribes, Flocks, and Single Servings — The Evolution of Digital Behavior

Koen Frenken, Juliet Schor (2017): Putting the sharing economy into perspective, Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions

Paolo Parigi, Bogdan State (2014): Disenchanting the World: The Impact of Technology on Relationships

Gig economy

The new ways of working enabled by platforms are referred to with term such as gig economy, on-demand economy or open talent economy. What is common to all of these is that they redefine the relationship between the employer and employee. While connecting supply and demand of work through a platform is nothing new, there is currently a massive growth in the size of the gig economy, fuelled by increasing online access and willingness to do disparate tasks.

Why is this important?

The welfare system, especially in the Nordic Countries, is based on the assumption of a steady employment with one employer. The current legislation and regulation is not capable of dealing with the new ways of working emerging from the platform economy as traditional criteria for what is considered as taxable income or work regulated by labour legislation no longer fits the scheme. Is everyone an entrepreneur in the platform economy or should the platform be viewed as an employer? How can social security and fair working conditions be ensured?

Gig economy proponents highlight the flexibility and freedom that platforms provide for the worker as well as the company. Especially SMEs benefit from the gig economy, as they are often agile enough to recruit quickly and are more prone to experience changing demand. Critics state that the work is unstable, isolating, stressful and devoid of welfare benefits. Gig economy favours highly skilled people with good health and thus may contribute to societal polarization. Furthermore, it is driving wages down globally, as platforms enable outsourcing of a variety of tasks, thus expanding the global marketplace.

Things to keep an eye on

To ensure fair and decent working conditions, a mix of regulation, new practices and worker collective action is required. The big benefit but also the central challenge with gig economy is that it is global. Regulation puts countries at different positions and workers have a tough time coming together and bargaining in a dispersed global network. For new practices and ways of operating, platform cooperatives are worth keeping an eye on.

For a company wanting to benefit from gig economy the focus should be on improving human relation practices. Employing should be swift and there should be a good balance between full-time and temporary workers. Different metrics to gauge employee satisfaction and working conditions should be in place and up-to-date.

Selected articles and websites

What’s After The Gig Economy? The Talent Economy

What the Gig Economy Looks Like Around the World

How The Gig Economy Will Change In 2017

The Gig Economy Celebrates Working Yourself To Death

Harnessing The Power Of The Open Talent Economy

10 Ways the Gig Economy Can Help Small Manufacturing Businesses

LinkedIn Finds Small Businesses Driving Gig Economy

Ukko.fi saa tuhat uutta asiakasta kuukaudessa – “Lainsäädäntö ei pysy mukana”

Mistä on kevytyrittäjät tehty?

Accounting of information flows: Data balance sheet

Systematic accounting of data and information flows is about to be acknowledged as an integral part of regular internal and public reporting by organisations. Alongside finances and corporate social responsibility, the topic of data has now found its way to annual reports. Forerunners publish even dedicated accounting reports for data and information flows, something which can be recommended in data-driven sectors.

For example, Finnish Transport Safety Agency Trafi recently published their second data balance sheet (tietotilinpäätös), an annual report describing their data strategy, related architectures and inventory of data and information flows. This supports Trafi in their aim to be a forerunner in collecting data but also opening it up for maximum use for societal benefit. Through digital public sector services and open data policy, Trafi among others encourages data flows between authorities, between authorities and (typically data-producing) users and towards companies to boost business. Examples of Trafi’s data include statistics and registers on vehicles, licences, permits and accidents. Another pioneer in data accounting is the Finnish Population Register Centre, having compiled data balance sheets since 2010, although due to the nature of the registers only a summary of the report is available for the public.

Why is this important?

Platform economy is all about unleashing the cornucopia of opportunities linked to data. Users and producers as well as the functioning of the platform create, process, store and exchange data, and these data and information flows form the key type of interaction in platform economy. Furthermore, many of the emerging technology areas linked to platforms, such as artificial intelligence, blockchain or automation, are extremely data-intensive.

Management of data has therefore become an increasingly critical and strategic part of activities of companies, public sector authorities and even individuals. On the one hand, data is an asset of real value, but on the other hand, this value can only come to fruition and grow through sharing and opening. This challenges existing business logics in many sectors, where data previously had little or no role or where data flows and information systems used to be strictly in-house matters.

Arguments favouring the introduction of data accounting to regular managerial and strategy work of organisations include both discovering opportunities but also addressing threats and uncertainties. Systematic data accounting helps internal monitoring and improvement, and an open approach helps to expand collaboration and partnerships with others (users, customers, companies and authorities). Accounting should also include responses and preparedness for safety and security issues as well as strategies related to data ownership, surveillance and fulfilment of possible regulatory requirements.

Things to keep an eye on

A significant change factor in the topic of data management in Europe is the data protection regulation (EU) 2016/679 that is to be applied in all European Union Member States in May 2018. This regulation addresses the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data.

European Data Protection Supervisor lays out a definition of accountability in the meaning that organisations need to “put in place appropriate technical and organisational measures and be able to demonstrate what they did and its effectiveness when requested”. Suchlike measures include “adequate documentation on what personal data are processed, how, to what purpose, how long; documented processes and procedures aiming at tackling data protection issues at an early state when building information systems or responding to a data breach; the presence of a Data Protection Officer that be integrated in the organisation planning and operations etc.”

Another great resource on the topic is the recent publication by the Finnish Government´s analysis, assessment and research activities on use and impacts of open data. The report describes the openness of major data resources maintained by the public administration and on means to assess the economic impacts of open data in Finland. An analysis of the relationship between firms’ use of open data and their innovation production and growth is also provided. To conclude, the report proposes specific recommendations how to enhance the impact of open data in our society, including the use of tools such as data balance sheets.

The European Digital single market strategy and especially the subtopic of online platforms fits well into the above-mentioned discussion. Issues addressed under these activities include for example concerns about how online platforms collect and make use of users’ data, the fairness in business-to-business relations between online platforms and their suppliers, consumer protection and the role of online platforms in tackling illegal content online.

Guidance on how to prepare a data balance sheet is provided by for example the Finnish Data Protection Ombudsman in English and Finnish.

Selected articles and websites

General Data Protection Regulation (EU) 2016/679 – EUR-Lex

European Data Protection Supervisor: Accountability

European Commission: Digital single market – Online platforms

Valtioneuvoston kanslia: Avoimen datan hyödyntäminen ja vaikuttavuus

Liikenteen turvallisuusvirasto Trafi: Tietotilinpäätös 2016

Väestörekisterikeskus: Tietotilinpäätös

Data Protection Ombudsman: Prepare a data balance sheet

TechRepublic: Data’s new home: Your company’s balance sheet

Open innovation platforms

The concept of open innovation has been around for some time. The basic idea is that organisations open up their innovation processes to other companies as well as end-users and other stakeholders. Besides traditional face-to-face workshops and physical innovation spaces, digital platforms can be used to facilitate the matching between challenges and solutions, to prioritize ideas and to offer a place for collaboration and co-creation. Hackathons are an example of modern innovation platforms combining the best of the physical and digital innovation platforms.

Why is this important?

Open innovation platforms benefit at best the whole innovation ecosystem or network. Problems get solved quicker, new solutions are more suitable for end-users and stakeholder collaboration is enhanced. Digital solutions also broaden the outreach and allow participants of different backgrounds, expertise and location to contribute. While open innovation platforms have been used internally in companies and more openly in research and development, digital solutions are finding their way also to the public sector, especially to citizen engagement in local communities. This makes city development more transparent and opens up the door for smaller companies to compete in public procurement.

Things to keep an eye on

The current trend is towards more openness and from company ownership to network-based shared ownership of the innovation platform. Instead of a company having its own open innovation platform, the platforms are framed as ecosystem level collaboration spaces or solution marketplaces. On the public sector side open innovation platforms are used not just for seeking technological solutions to societal challenges, but also to foster social innovation. However, there are underlying questions that for the time being remain open, e.g. who owns the intellectual property at the end of the day, what are the benefits or compensation for participants or who all benefit from the platform .

Selected articles and websites

How open innovation platforms support city development?

TOP 10 Open Innovation Platforms

Open Ecosystem Network

The visibility of ethics in open innovation platforms

16 Examples of Open Innovation – What Can We Learn from Them?

Integrating Open Innovation Platforms in Public Sector Decision Making: Empirical Results from Smart City Research

Sitra: Ratkaisu 100