This signal post provides an overview of progress and expected future directions of digital platforms in the context of food. Firstly, we take a look at existing platforms of different type within the consumer interface. Secondly, we explore the wider opportunities of platforms along entire food production chains and ecosystems. Thirdly, we identify a handful of emerging platform innovations waiting to enter the markets.

Platforms for the consumer

In the context of food, digital platforms for consumers can make the daily life more convenient, efficient and affordable. Comparing choices is easier, payments happen online and deliveries can be arranged too. Special deals and personalised offers are being increasingly used, and customer review systems act as an in-built quality control measure. Digital platforms may also serve as gateways to widen the range of accessible choices for consumers or bring additional benefits such as social connections. A platform can help arrange a lunch date with a potential new business partner or connect like-minded people to cook and eat a meal together.

Platforms for everyday grocery shopping remain for the time being primarily company-specific initiatives, as large grocery retailers that dominate the traditional markets have preferred to build their own platforms rather than common marketplaces. The restaurant business, specialised small-scale producers and consumer-to-consumer segments have, on the contrary, been keen to adopt platforms based on two-sided or multi-sided markets. Examples of these include:

- platforms for finding, booking, paying and reviewing restaurants, e.g. Eat.fi (Finland + international) and Foursquare (USA + international)

- platforms for ordering and paying takeaway food or food deliveries from restaurants, e.g. Pizza-online (Finland), Wolt (Finland + international) Foodora (Germany + international) and Uber Eats (USA + international)

- platforms for buying and paying for food and groceries directly from typically small or local producers, e.g. Farmhouse (Australia), OurHarvest (USA), Maano (Zambia) and Forestfoody (Finland)

- platforms for buying and paying affordable surplus meal deals or food products from restaurants or grocery wholesalers, e.g. ResQ (Finland + international) and Fiksuruoka.fi (Finland)

- platforms in the consumer-to-consumer space such as meal sharing, pop up activities, food swap, etc., e.g. Ravintolapäivä (Finland + international), Meal Sharing, foodsharing (Germany) and Traveling Spoon.

It is notable that many of the established and emerging platforms contribute to (economically, environmentally or socially) sustainable consumption patterns and sharing economy principles. Restaurants and households alike are minimising food waste, and social connections and community spirit are fostered through local activities. Even the food delivery services are, instead of simply increasing motorised transport and related negative externalities, growingly using sustainable alternatives like bike couriers.

Platforms for the food production chain

Digital platforms have potential also in capturing entire supply chains and supply network ecosystems of food production. The food industry is, in fact, an exceptionally interesting application area, because benefits of digitally managed production chains do not limit to the obvious efficiency savings but extend to topics such as food safety, cold chain management and transparency in production conditions and origin.

One example of future opportunities with digitalisation is the so called Food Economy 4.0 that paints a picture of a sustainable consumer-centric ecosystem. The core of this concept relies on three change paths: (1) from mass production to personalised solutions, (2) from centralisation to agile manufacturing and delivery and (3) from horizontal to vertical food production. In Finland, a strategic roadmap has even been drafted to an envisioned consumer data-driven, digital platform model to disrupt inflexible and inefficient value chain structures among primary production, various industry sectors, logistics, retail and service sectors in the food chain. This concept foresees that industrial platform creation could proceed step-wisely and ultimately evolve from transportation, warehousing and market platforms into long-term interoperability across industries and platforms.

Similar ideas relating to the currently linear, industrialised and centralised food supply chains are also promoted in examples such as food hubs, precision agriculture and analytics, recycling applications and dietary information systems. Even if we currently see these concepts emerging as standalone applications and platforms, the next step forward would be to embed and interconnect them throughout value networks. Stakeholder collaboration and novel thinking will be a necessity, but synergetic effects and added value are expected to be substantial.

Longer term visions

Even more innovative long-term visions for food in the platform economy include initiatives that plan to use blockchain technologies to manage transactions. Russian-originated INS Ecosystem plans to transform the push-based grocery business to a pull, using a dynamic system to fulfil orders and adjust prices by connecting sellers and buyers directly. This efficiency improvement would minimise the need for shelving foods and also reduce waste. Another similar decentralised marketplace initiative is BlockFood with its technical architecture based on smart contracts that allow customers to order food from restaurants and have it delivered. A third example, FoodCoin, has perhaps even more ambitious plans, aiming to create a global marketplace of food and agricultural products using the Ethereum technology. The platform would engage all actors along the supply chain from farmers and equipment manufacturers to food manufacturers, restaurants and consumers. All of these platforms have advanced plans to make use of tokens and cryptocurrencies.

But what if the food itself that we consume will change dramatically? Powdered meals and personalised food fabrication are examples of such innovations. These would implicate even wider opportunities for digital platforms, as instead of traditional recipes and supply chains the demand would expand to smart, personalised diet planning and novel nutrient markets. The focus could thus move from platforms optimising logistics to platforms providing intelligent nutritional solutions that are tailored to personal needs. Further on, personalised approach to food to improve wellbeing and health could even be combined with measuring and monitoring of your daily condition, genetic information and personal goals. And all of this could be interlinked to platforms that use nudging and positive reinforcement to encourage positive behavioural patterns in our daily choices, a step forward from what platforms like Zipongo are already exploring.

Selected articles and websites

Allfoodexperts: Food powder. Eat what you like

Allfoodexperts: Sharing Economy Reaches Food: Startups Based on Collaborative Networks

BlockFood: BlockFood is the world’s first decentralized food ordering & delivery platform

Complexity Labs: Food Systems Innovation

FoodCoin Ecosystem: Global blockchain ecosystem for food and agriculture businesses

GreenBiz, RP Siegel: This blockchain startup is hungry to address the grocery industry’s food waste dilemma

INS Ecosystem: A Decentralized Online Grocery Marketplace: How it Works for Consumers

Kotiranta et al. (2017): Roadmap for Renewal: A Shared Platform in the Food Industry

MedTech Engine, Mariëtte Abrahams: The personalised nutrition trend – how digital health brands can revolutionise healthcare

News.com.au, Frank Chung: CSIRO sets sights on personalised ‘food generator’ based on your DNA, lifestyle and even sweat

Platform Value Now, Heidi Auvinen: Digital platforms for supply chains and logistics

Poutanen et al. (2017): Food economy 4.0 VTT’s vision towards intelligent, consumer-centric food production

The Technology Media, Elina Koskipahta: The platform combines feedback from journalists, food critics and local users

World Food Program: Maano – Virtual Farmers Market

Zipongo: Eating well made simple

Public sector ambitions in the platform economy

Ecosystems in the platform economy can accommodate all and any stakeholders, and the public sector among other actors can decide on the degree of ambition in the role they want to take. The most lightweight option would be to simply follow the field and allow market driven development of platforms proceed. In a more active mode the public sector would monitor and react to upcoming challenges and, for example, adjust taxation and regulation to match with the new landscape. Further on, a genuinely proactive role would entail active support for platforms and participation as a partner in platforms. The most ambitious option would be to aim to become a forerunner and contribute to strategic steering of the platform economy development. In this role the public sector could take on responsibilities in ecosystem facilitation but also show the way by embedding public services and internal processes to platforms.

In this signal post we introduce a few examples of the public sector taking ambitious and active part in the platform economy. These cases exemplify how visions are being turned into the new normal and how implementation steps have been taken in Finland and Estonia. The three topics covered are (1) platforms of open public data (serving among others further platform development), (2) provision of public services in platforms and (3) the visionary idea of citizenship as a platform (and for sale).

Open public data

Open public data means information produced or administered by a public organisation, and it is made available free of charge for private and commercial purposes alike, very much in line with the platform economy thinking. In Finland, metadata of public open data is collated in the Avoindata.fi service and then the European Data Portal. Although ‘work in progress’, many forerunner examples of novel open data initiatives are already running or under preparation. Often regulatory changes are needed to proceed towards open data effectively yet safely and securely.

Example: The Finnish Transport Agency maintains the NAP service (National Access Point), where since the beginning of 2018 all passenger transport service providers are obliged to open up their data on their services. The foundation for the system was laid in the innovative regulatory update, the Act on Transport Services, and accessing this data in the service, maintained by the transport authority, is expected to accelerate development of, for example, more comprehensive journey planners and advanced transport services.

Example: The government is proposing in Finland a new act on the secondary use of health and social data, intended to enter into force in July 2018. It would pave the way for a centralised electronic licence service and a licensing authority for the secondary use of health and social data. Finland already has extensive high quality data resources that could be put to more flexible and secure use instead of the current situation of dispersed datasets in different information systems by different authorities. The new act aims to streamline data requests and access as well as improve data security and thus benefit research, innovation and business but also teaching, monitoring, statistics, official planning, etc.

Public services in platforms

Digitalisation, in general, has been widely adopted as a target in public service provision, but the platform economy provides an even wider opportunity to more efficient, more accessible and less bureaucratic services. Education and social services among others are already making first steps in employing platforms, and a platform of platforms could also be envisioned, enabling seamless information exchange and navigation between services. For example, imagine managing your academic milestones, entitlement to study grants or other social assistance as well as medical records or unemployment situation not using separate manual processes but interlinked platforms with one-stop-shop principle. For a first implementation step, platform synergies could be built along administrative branches, such as education, or along specific fields of activity, such as administrative processes linked to building, construction and environmental permits.

Example: Suomi.fi is an online service in Finland that functions as a portal to public services and information. Although not a fully developed platform of platforms, this online service already demonstrates the single point of access principle in action. Suomi.fi empowers the user to find and then access a multitude of public services as well as their information and authorisations. For example, you could use the service to check your vehicle registry information and, if necessary, communicate electronically with the authorities to update it.

Citizenship as a platform

One imaginative or even utopian idea is to bring not only public sector data or services into platforms but to provide and exercise citizenship as a platform. Ultimately this would mean that an individual could choose their preferred digital citizenship platform and thus be, for example, entitled to public services and subject to taxation according to this choice. Citizenship as a digital platform would allow individual value-based decisions on citizenship rather than based on criteria such as country of birth. While the full concept remains theoretical, the first partial applications are running.

Example: E-Residency is a government issued digital identity launched by the Republic of Estonia in late 2014. It allows entrepreneurs from anywhere around the world to set up and run a location independent business but does not entail, for example, tax residency or citizenship rights to reside in Estonia. This legal and technical platform is the first of its kind, and the digitally accessible user benefits include company registrations, document signing, online banking, etc. The system also contributes to more transparent financial footprint through monitoring of digital trails. Between the launch and February 2018, over 33 000 applicants from 154 countries have established over 5 000 companies as e-Residents.

Selected articles and websites

Avoindata.fi − Open Data and interoperabilty tools

European Data Portal

Finnish Transport Agency: Service providers of passenger transport can now store data in the NAP service

Ministry of Finance: Open data: Opening up access to data for innovative use of information

Ministry of Social Affairs and Health: Secondary use of health and social data

Republic of Estonia: eResidency – Become an e-resident

Suomi.fi – information and services for your life events

Wikipedia: e-Residency of Estonia

Interpreting the platform economy against landscape-level change factors

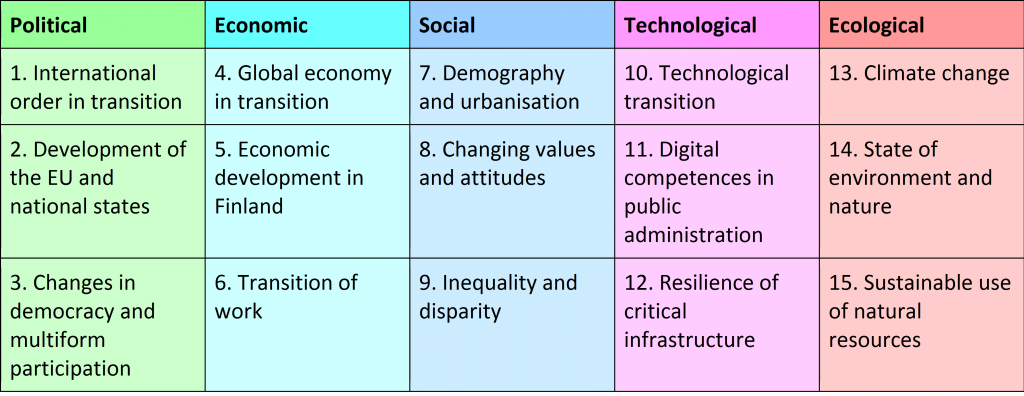

The Prime Minister’s Office in Finland published in late 2017 a list of change factors of the global landscape, with the aim to familiarise decision-makers as well as citizens with the changes and uncertainties we will face in the future. The result of fifteen key factors of change was produced in collaboration with experts across ministries and their strategy work. They also provide the basis for dedicated futures outlooks by various ministries to be published later in 2018.

The fifteen change factors each introduce the identified change and describe the situation until 2030. Additionally, alternative paths and development directions are offered. Rather than predictions, the change factors help prepare for various alternatives around the identified change topics, all the while acknowledging uncertainties.

In this signal post, the fifteen change factors are briefly analysed in the context of the platform economy. The idea was to formulate statements as questions and portray the alternative ways the change factor may be expressed in the platform economy. Some of the change factors can act as high level trends that steer platform development from afar, whereas others have very straightforward impact mechanisms. On the other hand, platforms themselves can influence the change factors and contribute to how the changes take place. The objective of this analysis is to help to map the potential with the platform economy regarding both opportunities and threats in the changing societal landscape. In fact, as the platform economy evolves, any of the issues identified may take a positive or negative turn or a combination of the two.

Political

- International order in transition

- Will the USA host as the basis for leading platform companies?

- Can China and the rest of Asia challenge the US leadership?

- Will platforms act as enabling tools in international policy-making?

- Will platforms be used as enabling tools for conflicts and corruption?

- Development of the EU and national states

- Will the EU develop into a competitive and uniformly close-knit platform economy?

- Could we face a failure of joint EU activities in the platform economy?

- Are there going to be nationally or regionally confined platform economies?

- Changes in democracy and multiform participation

- Will platforms act as enablers of accessible knowledge and the information society?

- Will platforms be used to spread polarisation and misinformation?

- Will platforms be employed as tools to societal participation in democracy?

Economic

- Global economy in transition

- Are we going to see globally reigning platform monopolies or local platform economies?

- Is the economic growth from platforms around the world going to be even or uneven?

- Will platforms support quick profits or sustainable growth?

- Economic development in Finland

- Will Finland succeed as a balanced platform economy on its own?

- Is Finland going to excel in its niche areas in the global platform economy?

- Will Finland remain a minor actor in the platform business?

- Transition of work

- Is all work going to be gig work on platforms?

- Could education, training and skills be provided on platforms on an on-demand basis?

Social

- Demography and urbanisation

- Can platforms bring along a counter-trend to urbanisation and migration?

- Could platforms help to solve challenges related to ageing?

- Will platforms be used as connectors between culturally or demographically differing groups?

- Changing values and attitudes

- How will ethics and values be incorporated into platforms?

- Could different platforms support variability in choices on lifestyles and values?

- Will platforms be used as a destructive force?

- Inequality and disparity

- Will platforms be employed to empower women and build equal opportunities globally?

- Will platforms be used to aggravate polarisation of individuals and nations?

- Can platforms contribute to accessible human health and wellbeing?

Technological

- Technological transition

- Will blockchain, AI, robots, etc. be employed successfully in platforms?

- Is the role of platforms and advanced technologies to be in control or as a subordinate?

- Could we face technological underachievement and failure of the platform economy?

- Will data be the currency of the future technological platforms?

- Digital competences in public administration

- Will the public sector be active in platform management and participation?

- Is public administration going to be incapable of deploying digital platforms in their own processes?

- Can the public sector keep up with platform markets?

- Resilience of critical infrastructure

- Will platforms bring intelligence into infrastructure management?

- Will we be able to ensure resilience regarding digital infrastructures and cyber security?

Ecological

- Climate change

- Could platforms and advanced technologies contribute to effective agreements in climate policy?

- Will digital platforms increase or decrease the overall environmental burden?

- Could the platform economy provide the means to survive with climate change impacts?

- State of environment and nature

- Could platforms facilitate monitoring of natural and built environments?

- Sustainable use of natural resources

- Could platforms be used as enabling tools for material and resource management, e.g. recycling?

- Will sharing platforms promote effectively sustainable, resource-efficient lifestyles and economies?

- Will unsustainable consumption patterns spread uncontrollably because of platforms?

- Are platforms, data and related technologies going to increase energy consumption exceedingly?

Selected articles and websites

Ethics in the platform economy

Technology development has reached the phase where technology provides direct actions and services without the need of a human being involvement. In platforms, data is the asset and multiple technologies are used to collect, store, analyse, share and present the data. AI makes analyses, diagnoses and decisions, robots perform human like actions and mobile phones offer everybody an access to the integrated systems (platforms) formed by the new and emerging technologies. The novel systems are not only showcases any longer but they are an essential part of our everyday life. Therefore, ethics plays an important role in these complex systems and needs to be studied carefully.

In this signal post we discuss the ethical challenges of platforms and the applied technologies and explore the possibilities to take ethics into account when designing and developing new systems.

Ethics and emerging technologies

Ethics refers to “moral principles that govern a person’s behaviour or the conducting of an activity”, “the moral correctness of specified conduct” or “the branch of knowledge that deals with moral principles”. The minimum set of ethical and moral principles are implemented in laws and regulations, which often are trailing behind the technology development. One example of such a situation is the collection and use of data: the big platform players have collected personal data for years and used it in building their systems and services. Now the EU is launching the General Data Protection Regulation (Directive 95/46/EC) which will be in force on 25 May 2018. Another area of current ethical concerns is the autonomous vehicles, both for civil and military purposes. In case of autonomous cars, how should the optimization be made, whom or what (human welfare, safety of the passenger or those on the road, environment, etc.) to prioritize and on what grounds?

On the other hand, ethical challenges in the medical and pharmaceutical R&D have been identified in time and the regulations and codes of conducts were first developed there and are in place in developed countries. However, the emerging technologies constantly trigger new ethical issues. Current ones include the genome editing and the use of robots in taking care of patients or elderly people. The modern health care platforms tend to imply all possible ethical issues from personal data protection to the use of AI and robots in any imaginable combinations.

Ethics assessment

In case of the development and application of emerging technologies, regulation may not always be timely enough and more generic forward looking guidance is needed. The EU SATORI project developed a CEN workshop agreement on ethics assessment and an ethical impact assessment framework for research and innovation. IEEE has introduced a Global Initiative for Ethical Considerations in Artificial Intelligence and Autonomous Systems. Its General Principles Committee seeks to articulate high-level ethical concerns that apply to all types of artificial intelligence and autonomous systems that:

1) “Embody the highest ideals of human rights that honour their inherent dignity and worth.

2) Prioritize the maximum benefit to humanity and the natural environment.

3) Mitigate risks and negative impacts as AI/AS evolve as socio-technical systems.”

In an ideal world, the ethical principles should be harmonized to avoid the “distant working” in such countries where the regulation allows the unethical actions. The harmonization is challenging because the interpretation of ethics is based on moral principles and those vary from culture to culture. Discussion and collaboration between technology developers, philosophers and sociologists are needed to develop the principles and necessary codes of conducts. The transparency offered by social media platforms can be helpful in raising the awareness of ethics. When taking the issue further, the prevailing culture should be built into the systems if we don’t want the systems to develop our culture in the future.

Selected articles and websites

Directive 95/46/EC, The General Data Protection Regulation

Ethics assessment for research and innovation – Part 1: Ethics committee

Ethics assessment for research and innovation – Part 2: Ethical impact assessment framework

Finland Banks on Medical Robots to Facilitate Elderly Care

SATORI- Stakeholders Acting Together On the ethical impact assessment of Research and Innovation

Shashkevich, A., Stanford scholars, researchers discuss key ethical questions self-driving cars present

The IEEE Global Initiative on Ethics of Autonomous and Intelligent Systems

What are genome editing and CRISPR-Cas9?

Digital platforms for supply chains and logistics

Supply chains are complex systems that typically involve a multitude of actors and activities, and it can be extremely difficult to capture one entire chain, let alone the networks of criss-crossing and interlinked chains. A platform of some sort is needed to put suchlike chains together. The concept of platform economy as we understand it, involving digital platforms and advanced accessory technologies such as blockchain, offers in this context vast opportunities to more efficiently managed supply chains and logistics. Information over chains and networks can be gathered and processed in platforms, which not only helps steering and monitoring of entities but may facilitate optimisation of chains, produce reliable accounts, inspire new business innovations, etc.

In this signal post we explore possibilities with platforms for supply chains and logistics and take a look at examples from forerunner industries.

Information management in multi-actor supply chain networks

Digital platforms allow information management throughout the supply chain, enabling data to accumulate from each step of the chain. Simultaneously, access to data can be granted to any involved actor, including the end user. In essence, a product or service can be accompanied by a digital twin, i.e. a virtual counterpart for gathering data and information over the lifecycle from design and manufacturing to use and final disposal.

One practical example comes from diamond business, where platforms and blockchain technologies are used for the digital record for diamonds, especially to verify origins and authenticity. Similarly, Walmart among others is piloting tracking of food products to support food safety. Suchlike information platforms serve especially the end customer, who can be sure of, for example, the origins, fair production conditions or undisrupted cold chain of the product or service that they buy. But also supply side actors benefit, and one well established example of using backfeed information comes from elevator industry, where Kone has successfully deployed IoT-type solutions to make use of real-time information collected from their products to serve maintenance services as well as product development.

Research on this area is intensive, see for example a study from our project on platforms being used in service-driven manufacturing to orchestrate networks.

Platform innovations in freight and logistics

Logistics constitutes one specific chain of activities in supply chains. Platforms and blockchain have huge potential in this area; a fact acknowledged lately in the Transport Sector Growth Programme by the Finnish Government (full report in Finnish). Firstly, information stored on digital platforms can make the logistics chain faster and more efficient, for example by providing real-time information from one phase to the next or by replacing manual bureaucratic processes with digitalised and automated equivalents. Information of movements but also information of transport related emissions could be recorded reliably.

Secondly, platform economy enables new types of business models for logistics services, as information of material flows is available to construct centralised as well as decentralised delivery streams in new ways. For example, in urban freight novel app-based logistics services have emerged, especially as a response to growing e-commerce. Suchlike commercial and peer-to-peer services can connect demand and supply for instant deliveries via a digital platform in just a few hours. A more large-scale example is the free web-based freight brokerage platform Drive4Schenker that functions as a European-wide marketplace for deliveries and supports digital handling of documentation.

Selected articles and websites

CBINSIGHTS: How Blockchain Could Transform The Way You Buy Your Groceries

Dablanc Laetitia et al. (2017): The rise of on-demand ‘Instant Deliveries’ in European cities, Supply Chain Forum: An International Journal

DB Schenker: Drive4Schenker

Eloranta, Turunen (2016). Platforms in service-driven manufacturing: Leveraging complexity by connecting, sharing, and integrating, Industrial Marketing Management, Vol 55, pp. 178-186

Finnish Government: Transport Sector Growth Programme will give companies a boost in the international market

Forbes: IBM Forges Blockchain Collaboration With Nestlé & Walmart In Global Food Safety

Fortune: The Diamond Industry Is Obsessed With the Blockchain

Fortune: Walmart and IBM Are Partnering to Put Chinese Pork on a Blockchain

Kone: Taking elevator services to the next level

Ministry of Transport and Communications: Applying blockchain technology and its impacts on transport and communications

Techncrunch: Blockchain has the potential to revolutionize the supply chain

Työ- ja elinkeinoministeriö: Liikennealan kansallinen kasvuohjelma 2018 – 2022

World Economic Forum: The digital transformation of logistics: Threat and opportunity

Platforms for education and learning

A digital platform is in many ways the ideal tool to manage inflow, storage and outflow of knowledge. Data, information, news, knowledge and other types of content can be produced and collected on a platform. A platform also serves as a mediator and broker of these contents, providing access and enabling algorithmic or collaborative means to process it. Furthermore, a platform provides an interface for absorbing knowledge, i.e. to learn, study and be informed.

In this signal post we will have a look at some examples of platform economy entering the world of education and learning. The two topics under analysis are: (1) e-learning platforms in formal education and (2) online education resources and degrees.

E-learning platforms in formal education

Online platforms have been adopted in formal education on levels. Schools and universities manage their curriculum, learning materials, assignments, distance education, etc. in platforms. These e-learning platforms help the educational establishments and teachers to organise their work as well as the students to organise theirs. In a way, you could think of the platform being the teachers’ room, classroom and personal study space in one. Online environment additionally facilitates collaboration, for example between students in projects or between teachers, students and parents. E-learning platforms have replaced some of the previously ‘manual’ functions, but they have also provided completely new opportunities. In the big picture, they do nevertheless support and complement traditional classroom-type formal education rather than fully replace it.

One of the best known e-learning platforms is Moodle. It belongs to the tradition of open source software, and it is popular all over the world. The key traits of the system include the opportunity to scale, adapt and modify it and the flexibility to create personalised learning environments under one umbrella.

Online education resources and degrees

Another type of application of the platform economy is the fully online education and learning platforms such as Khan Academy (free online learning resource) and Udacity (free online classes and commercial nanodegrees). Suchlike platforms can provide programs similar to those by formal educational institutions or smaller study entities for vocational or personal learning. Online education resources and degrees are typically open for all, enabling worldwide attendance, and targeting mainly adults. Some function as free non-profit initiatives while others are run as profitable businesses, much like open universities and municipal or commercial education centres.

For example, Khan Academy provides a free, no-ad online education platform that partners with respected institutions such as NASA and MIT. The offering stretches from kindergarten level to science and programming. Udacity, on the other hand, has developed a so-called online nanodegree program product, where industry leaders and expert instructors offer a personalised learning experience. These intensive programs of 6-12 months even guarantee the graduates to land a job within six months of graduation or their tuition is refunded.

Things to keep an eye on

While the platform economy is employing digitalisation to make education and learning more efficient and accessible, there are also factors of uncertainty and risk. One question of uncertainty is what will be the future balance of formal and informal education. New types of education platforms may in fact have a significant role as the timely provider of new skills and competences required at different career stages. Another issue is the risks involved in the online environment, where it is difficult to verify quality or address ethical and cultural aspects of the vast flow of new information and new services.

Regarding advanced technologies linked to the platform economy, such as blockchain and artificial intelligence (AI), the education sector among others is likely to be affected. For example, the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre’s (JRC) recently published a study on blockchain in education, and the report describes promising opportunities to involve blockchain technologies in student information systems and granting or verifying certificates, etc. And according to cloud platform company Tokbox, AI may further transform the education experience by bringing along for example smart content, intelligent tutoring systems, 3D environments and universal online learning.

Selected articles and websites

Grech, A. and Camilleri, A. F. (2017). Blockchain in Education. Inamorato dos Santos, A. (ed.)

Liu, H. Men and J. Han (2009). Comparative Study of Open-Source E-Learning Management Platform. 2009 International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Software Engineering, Wuhan, pp. 1-4

Khan Academy: A personalized learning resource for all ages

Moodle: Moodle learning platform

TokBox: The Edge of Automation: Artificial Intelligence in Education

Udacity: Free online classes and Nanodegrees

Guest post: Rules and laws for platforms (Youtube gaming)

This time we have a guest author, who provides a fresh and personal view into the platform economy. Akseli spent two weeks at VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland Ltd in November 2017, completing his work practice programme. One of the tasks Akseli took on was to familiarize himself with the concept of the platform economy and write his very own signal post on a topic of his choice.

Akseli chose to look into Youtube gaming, and how gaming companies, gamers and regulators are currently in a difficult situation. Many interesting things are happening in this area, but the rules of the game are not always so clear…

Hi! I’m Akseli Ala-Juusela, I’m 15 years old, and I was instructed to write a blog post on platform economy, so here we are!

Many people around the world take advantage of platforms like Uber, AirBnB and Youtube. Some problems have emerged, though, as huge corporations are looking for their share in advertisements and profits from the platform.

Challenges of Youtube gaming

I’m going to use Youtube as an example since I’m most aware of its issues. You see there are underlying problems for anybody trying to play videogames for an online audience. The entertainers need to have written permission from the maker according to some, and just purchasing the game and commenting on what is happening on the screen is enough according to others. There are some clear copyright violations like uploading the whole of Star Wars to Youtube without permission from Lucasarts and Disney. But there are also some borderland cases, for example, playing a game while adding your own jokes and commentary.

This leads to all kinds of law talk that I will never understand without going to a law school. But the gist of it is that one court decision could kill a big business and ruin lives of game based internet entertainers who are one of the biggest things dependent on Youtube. These channels are desperately trying to migrate to other forms of entertainment like vlogs (video blogs) and skits (comedy shorts).

We need worldwide rules

The only smart way of going about it is by defining the rules of the internet that will either affect on a global or a local scale. I would suggest the global version as it is much easier to regulate and harder to bypass. The only problem with global rules is that it is hard to punish those you don’t find or can’t reach.

Youtube also has a unique problem that they will probably never completely solve: there are 300 hours of video added there daily [1] which makes weeding out propaganda and terrorists a lot harder. Some countries like Germany require platforms like Youtube to take illegal content off in 24 hours [2], so it is near impossible to please everybody. More so, Germany threatens with a 5-50 million euro fine for not complying so the answer to them was to make a bot that could identify and eliminate anything that could be considered as inflammatory or illegal.

In conclusion: In my opinion, this is a lackluster way to handle situations, and we need a wider set of internationally recognised rules, that are endorsed, for online platforms.

Selected articles and websites

[1] Fortunelords: 36 Mind Blowing YouTube Facts, Figures and Statistics – 2017

[2] BBC News: Germany votes for 50m euro social media fines

A big thank you to Akseli!

Finland’s master plan for platform economy

A couple of weeks ago (October 2017) the Prime Minister’s Office, Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment and Finnish Funding Agency for Innovation Tekes published the national roadmap for digital platform economy for Finland. The first half of the report paints the present picture of the platform economy as a global phenomenon and Finland’s position in it. The second half drills into the national future aspirations for success and growth and introduces a vision and roadmap for Finland. Furthermore, an atlas of ten sector-specific roadmaps is presented and an action plan to fulfil the vision is outlined.

Top-down meets bottom-up

Finland is a pioneer in launching such a comprehensive national vision, roadmap and implementation plan for digital platform economy. Germany, Japan, Singapore and even the EU have touched upon the topic in their industrial or STI (science, technology and innovation) policies, but not with such focused dedication as Finland. The Finnish strategy is to harness platform economy as an enabling tool that has potential to generate growth for businesses as well as enhance productivity of the entire society. A key element of the vision is to develop national competitive edge out of the platform economy.

But why the choice of national and collective approach, when the leading platforms (from the US) have typically emerged as market-based business innovations? The Finnish initiative seems to embrace the platform economy as a wider phenomenon that covers the potential for value creation and capture not just for companies but for citizens and the state alike. Platform ecosystems therefore extend to all actors in the society, and governmental institutions can step up to take active part. According to the report, the foreseen role of public sector includes for example:

- facilitating society-wide dialogue and aligned national vision

- implementing a competitiveness partnership between public and private sectors

- strengthening the development and business environment for platforms

- developing the knowledge base, resources and tools

- showing example by open public data and platforms launched by the public sector

- other enabling support such as regulative measures.

In short, the Finnish hypothesis for how to accelerate and benefit from the platform economy is to activate both the bottom-up (innovators, businesses, individuals, etc.) and top-down (governments, authorities, regulators, etc.) stakeholders. No getting stuck in the chicken-and-egg dilemma, but getting started on all levels and in a nationwide public-private-partnership.

Other interesting messages

Strengthening of the knowledge base and education to support skills in the platform economy has received a lot of attention in the Finnish roadmap report. This covers both formal education as well as further training along the career path. What is especially highlighted is software design skills, but what about entrepreneurial mindset, data-driven innovativeness and cross-sectoral service thinking?

The value of data and the vast potential for its usage is also emphasized in the report. Data economy as a concept is being mentioned, and especially the role of the public sector is explored in terms of developing rules, providing common technical specifications as well as showing the way with public data resources.

Selected articles and websites

National roadmap report: Digitaalisen alustatalouden tiekartasto

Videos from the launching event (October 23, 2017): Suomi ja tekoäly alustatalouden aikakaudella

Further information: Suomi ja tekoäly alustatalouden aikakaudella

The environmental footprint of the platform economy

The platform economy is inevitably responsible for a myriad of environmental impacts, both positive and negative. These impacts are, however, difficult to identify and measure because of the complex impact chains and rebound effects. Very little research results (especially quantitative) on the topic exists at present moment. In the accompanying video, we list some key factors of the environmental footprint of the platform economy relating to (1) technology, (2) digitalisation and (3) patterns of consumption and production.

Technology

Platforms, as any other digital products and services, rely on large volumes of data centres and computing power. These require considerable amounts of energy, especially in the form of electricity and cooling. On the other hand, in the most hands-on meaning of technology, we need various devices to access platforms. Production of smart phones, tablets, computers, etc. is resource consuming and new models come up constantly. Short-lived, out-dated devices end up as electronic waste.

Digitalisation

Intuitively one might assume that through digitalisation, the platform economy would replace physical and material functions with digital and virtual solutions, and thus diminish use of natural resources and reduce harmful environmental impacts. But in fact, oftentimes platforms have a way of mixing the virtual and physical worlds, in some cases even accelerating material transactions. Secondly, digitalisation enables a global outreach, which in turn can increase global logistics. We have already seen this phenomenon with ever-growing online market places with global user populations.

Consumption and production

Perhaps the most intriguing and crucial factor is the question of consumption and production patterns in the platform economy. It brings us to analyse issues such as societal values, user behaviour, business strategies and political agendas. Will our underlying objective within the platform economy be “more with less”, “more and more” or “less is more”? The topical concepts of the circular economy and sharing economy highlight sustainable and responsible aspirations. In the optimal case the platform economy can align with these concepts and for example implement in practice innovations that promote access instead of ownership.

Selected articles and websites

World Economic Forum: How can digital enable the transition to a more sustainable world?

MRonline: The hidden environmental impacts of “platform capitalism”

Government of the Netherlands, Ministry of Economic Affairs: Argument map The Platform Economy

Bemine, Emma Terämä: Sharing – more common than ever & an integral step on our way to sustainable consumption

Commons, zebras and team economy

The platform economy is much more than business giants Uber, Amazon or Google. Platforms can facilitate a transformation in ways of organising work, value creation, sharing, and resources. While the currently dominant development direction tends to favour large platform companies with monopoly statuses, alternative undercurrents can be identified.

Why is this important?

The focus in the platform economy has largely been on how it enables new ways to create value. Value comes from both users and producers while the platform adds its value to the ecosystem by providing tools for matching and curating the content. Network effects further multiply the value based on the extensiveness of the network.

The sole focus on value creation has, however, lead to ignoring the mechanisms by which value is distributed in the network. Platforms both mediate value creation and add value through connecting actors, sharing resources, and integrating systems, but the question is, how is this value shared? Especially platforms with near monopoly status tend to aggregate much of the value to the platform itself and not share it back to the users of the platforms in a fair amount. Platform companies, like other companies, give the surplus to their shareholders. In some cases, it could even be said that platforms exploit their users by treating them as workforce without benefits or as sources of data to be sold to advertisers. At the same time, little attention is put into how platforms serve society. The discussion is more about how they disrupt existing industries and navigate in the gray areas of legislation.

Three approaches challenging the dominant platform business

Although the big platform companies produce most of the headlines, there are interesting initiatives for alternative forms of platform economy. One is the revitalisation of the idea of commons. In the context of platforms and peer-to-peer economy, commons is understood as a mode of societal organisation, along with market and the state, and combines a resource with a community and a set of protocols. A key question related to platform economy is what data, tools or infrastructure should be treated as commons, how to govern them and how to build both for-profit and non-profit services on top of them. These and other questions of a “commons economy” are being experimented with in peer-to-peer initiatives, platform cooperatives, and blockchain-based distributed autonomous organizations.

In the same way that commons challenges the notion of ownership, a growing number of companies called “Zebras” are challenging the notion of growth. “Zebras” are companies that aim for a sustainable prosperity instead of maximal growth like “Unicorns”. They can still be for-profit but also do social good. An interesting question is whether platform economy can be used to transform the current growth-based economic system towards a more sustainable version, or will the “Zebras” as well as cooperatives and commons be left to the margins in the dominance of platform monopolies.

A third interesting idea utilising the new possibilities of connecting and collaborating through digital platforms is the idea of team economy by GoCo. It challenges the idea of a permanent organisation. In team economy, groups form around an issue or a problem and disperse once the work is done. In contrast to gig economy, the tasks aren’t simplified or clearly defined, but rather what needs to be done is jointly explored with the customer. A platform is needed to connect and offer a collaborative workplace but also provides a record of everything a person has done, a sort of online CV for the platform age.

It remains to be seen to what extent commons, “zebras” and team economy can influence the development of platform economy, but they are interesting ideas to keep an eye on.