This coming spring in Finland is going to entail lively political discussions. The campaigns for the Parliamentary Elections (April 2019) are already in full swing. And after having dealt with domestic issues, the European Elections will follow (May 2019). Political debates are taking place in the media as well as workplaces, schools and other arenas where people meet. This includes also digital meeting places, and platforms of different type are growingly important in delivering political messages with wide outreach.

In this signal post, we will discuss three aspects of how the platform economy is facilitating political discourse. We will identify both positive and negative impacts on democracy, especially at the time of elections. The three topics are:

- targeted political campaigns

- fake news in politics

- electronic and online voting.

Targeted political campaigns

Digitalisation and the platform economy are changing the way that political campaigns are carried out nowadays. Voting advice applications act as platforms for candidates and parties to declare their agendas and for voters to find a match from their point of view. Another way to benefit from the wide outreach enabled by platforms is for electoral candidates to be active on social media.

While the platform economy promotes broad societal discussions and better informed decision-making, new types of problems also arise. Organized mass campaigns are masked as non-political one-to-one chitchat. Data about voters is being collected, and platform giants together with consultancies like Cambridge Analytica have been known to take targeted political campaigns and personalized adverts to a whole new level. There is little transparency, and the ways used to influence voting decisions are questionable.

It is very appropriate that platform-based solutions have been developed to tackle these issues. In Finland, the Vaalivahti initiative has been launched to help citizens identify when political adverts are displayed on Facebook. A simple browser extension, based on the software developed by Who Targets Me, needs to be installed, and an analysis of political ads and why you were being targeted is provided. The platform maintains an up-to-date database of targeted political campaigns, which is open also for researchers and journalists to examine.

Fake news in politics

The 2016 US presidential election, and the alleged fake news attacks surrounding it, was a big wake-up call around the world. Studies and investigations have been conducted with the aim to reveal what really happened, how much fake news and misinformation was being released and by whom, what the real influence on voters was and whether the very election result was affected. One example is the recent study that suggests that the exposure of the average American to pro-Trump fake news was higher than that of pro-Clinton, but the authors emphasize that rash conclusions cannot be made based on this knowledge.

Fake news by foreign or domestic, political or economic actors has the potential to disrupt democracy, especially close to elections. The forms adopted range from fake news promoting to bashing one candidate, but they may also intend to inhibit political speech and suppress voting altogether. Social media and other platforms are being used as the tools and means to distribute fake news, and regulatory governance and rule setting may be needed to address these issues.

An example of suggestions to fix problems with regulatory measures is to require transparency of political advertising on digital media by informative real-time ad disclosure. Such data includes the sponsor, money spent, targeting parameters, etc. This real-time information provided along with the ad should also be compiled and stored for later review.

Electronic and online voting

Platforms can also facilitate the casting and counting of votes by using electronic means. For example, an electronic voting platform could build on voting machines at polling stations. Or, take a few more steps forward, an online voting platform could allow those entitled to vote exercise their right from anywhere, using any device as long as they can connect to the internet.

In Finland, the topic of electronic voting has been discussed from the early 2000s on and several studies and pilots have been conducted by the Ministry of Justice. Electronic voting at polling stations was trialled in three municipalities in the 2008 municipal elections, but problems were encountered in registering votes. Work to develop electronic voting was thus discontinued around 2010, but discussions were reopened in 2016. A working group was then appointed, and a feasibility study on the introduction of online voting in Finland was published in 2017. The conclusion was that even though viable electronic voting systems already existed, they did not meet the requirements and risks outweighed benefits. Core problems included, for example, the reliability of the system and guaranteeing verification and election secrecy at the same time.

New technologies, such as blockchain, may however help solve the issues mentioned above. Blockchain could be used to fight electoral fraud and vote buying while ensuring integrity and inclusiveness. Service development with blockchain-based voting platforms is vibrant, and pilots are showing great promise.

Selected articles and websites

Greenspon Edward and Owen Taylor (2018). Democracy Divided: Countering Disinformation and Hate in the Digital Public Sphere

Hunt Allcott and Gentzkow Matthew (2017). Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31 (2): 211-36

Ministry of Justice. 2017. Online voting in Finland, A feasibility study

Ministry of Justice. Electronic voting in Finland

Palermo Frank, Forbes. Is Blockchain The Answer To Election Tampering?

Palmisano Tonino, The Cryptonomist: Voting in the days of Blockchain technology

Vaalivahti

Who Targets Me

Wikipedia. Voting advice application

Components of trust in the platform economy: Ability, integrity and benevolence

Trust has always been a cornerstone to business success, and it has typically been developed through a personal contact with another person, organisation or brand. In this signal post we explore the importance of trust in the platform economy, where digitalisation provides a very different setting with new opportunities and threats. We use the well-established frame pieced together by Mayer et al. that views trust through its three components: ability, integrity and benevolence.

In the next sections we explain the three in the context of platforms and present some topical examples of trust problems and solutions. We focus on the viewpoint, where the user is the trustor and the platform is the trustee. However, it should be noted that these roles can also be studied in reverse, the user being the trustee and the platform the trustor. Furthermore, in platforms the trustor-trustee relationship is, additionally, often formed among two or more users or producers, or between users and producers.

Component 1: Ability

When we talk about trust, ability is the component which explains to what extent we believe that a platform embodies the competences needed to perform its tasks. Ability covers, for example, the technological skills and solutions to deliver the core service as well as preparedness regarding privacy, safety, data protection, etc.

Example: Review and rating systems are a well-established way in the platform economy to check the trustworthiness of platforms as well as their users and producers. Quality of services of all and any parties on supply or demand side can be evaluated, and reports of top performance and misbehaviour spread fast. Of course, even rating systems can be abused, but in practice they have proven very efficient.

Example: Blockchain has been envisioned to improve trust in terms of providing technological means to, for example, validate data integrity. In fact, it can be employed to promote the three factors of digital trust: security, identifiability and traceability.

Example: An important lesson the big platform giants have learnt is that when cyber-attacks happen, it is important to be open about it and inform the users of what happened and how the problem will be fixed. Preventive measures are naturally the top priority, but the user also needs to be able to trust a platform’s ability to react when hackers succeed.

Component 2: Integrity

Using integrity or honesty we assess whether a platform adheres to acceptable principles and keeps the promises it makes. The starting point for integrity is compliance with laws and transparent consistency in following service promises, delivery times, pricing, etc. Extended further, integrity measures how the values of the trustor and trustee (the user and the platform) meet.

Example: Trust can be compromised, when platforms (such as social media companies) collect and sell user data or allow fake news and fake identities in their systems. Even if such activities are legal, the essence of the issue is whether the platform is transparent and informs its users of what goes on and whether it takes an active or passive role in fixing possible problems.

Example: Trust and transparency can be fostered in platforms by engaging the user in the supply chain or sourcing process. For example, it is possible for the user in some platforms to follow their order in real-time and even take part in the decision-making (ingredients used, packaging materials, delivery times, etc.). Again, blockchain technology can be useful in these applications.

Component 3: Benevolence

Benevolence captures the intentions and motivations of a platform and whether these go beyond egocentric profit making. This component of trust blossoms when the user feels appreciated in a win-win relationship, where the value is created and distributed in a fair manner. Benevolence is all about caring, and it is the foundation for customer loyalty.

Example: A pattern we have seen with some of the current platform giants is how they grow from benevolent to predatory. At first such platforms emerge with a low-cost high-value offering, but trust may be compromised as personalised services become a trap, user policies and pricing are changed and the profit-seeking monopoly tightens its grip on both the producers and users.

Selected articles and websites

Afshar Vala, HuffPost Contributor platform: Blockchain: Every Company is at Risk of Being Disrupted by a Trusted Version of Itself.

Baldi Stefan, Munich Business School: Regulation in the Platform Economy: Do We Need a Third Path?

Frier Sarah, Bloomberg: Facebook Says Hackers Stole Detailed Personal Data From 14 Million People.

IBM: IBM Food Trust: trust and transparency in our food.

Kellogg Insight (The Trust Project): Cultivating Trust Is Critical—and Surprisingly Complex.

Mattila, Juri & Seppälä, Timo (7.1.2016). Digital Trust, Platforms, and Policy. ETLA Brief No 42.

Mayer, R., Davis, J., & Schoorman, F. (1995). An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust. The Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709-734.

Möhlmann Mareike and Geissinger Andrea (2018). Trust in the Sharing Economy: Platform-Mediated Peer Trust. In book: The Cambridge Handbook on Law and Regulation of the Sharing Economy.

Murray Iain: The Platform Economy Can Change the World.

Sangeet Paul Choudary, INSEAD Knowledge: The Dangers of Platform Monopolies.

Sitel Group: No Trust, No Business: Hub Forum 2018 Makes the Future of Commerce Clear.

The Conversation: Social media companies should ditch clickbait, and compete over trustworthiness.

Platforms are the new reality in transport

The transport and mobility sector is one area of the economy already benefitting in a big way from platform innovations. Megatrends of digitalization and servitization are having a major impact on transport systems around the world, and as a result the transport sector already functions, to a great extent, according to the principles of the platform economy. For example, we see app-based innovations in ride-sourcing (e.g. Uber) and in mobility as a service (MaaS) packaging (e.g. Whim). The pioneering platform companies in transport are becoming mainstream alternatives to traditional models that typically involve car ownership. User interest in access-focussed platform services such as these is growing. To support these developments, and to manage unintended negative impacts, new regulations have also been introduced (e.g. the Finnish Act on Transport Services).

The platform economy meets the current transport discourse

In recent years, the transport sector has eagerly adopted the terminology, business models and ecosystem approaches that characterize the platform economy. This is not only seen in entrepreneurial initiatives and business innovations but also in the public sector sphere. Decision-makers and policy planners have acknowledged the great potential of platforms to promote more sustainable mobility in terms of accessibility, flexibility, affordability, environmental performance, etc. Steering measures and regulations can help platform-based transport and mobility market grow in a sustainable manner, i.e. building on public transport services and with preference to environmentally and socially sound solutions.

In the current transport discourse, the term platform economy is already well established. Service providers identify themselves as platform owners, and politicians alike have grasped the opportunities involved with platform-based value creation (see, e.g. Anne Berner, the Minister of Transport and Communications of Finland). It has even been suggested, that the platform economy is the currently reigning ideology in transport policy.

Recent and expected developments in the field

Recent examples of new platform-based transport services in Finland can be found under Traffic Lab, an initiative by Finnish Transport Safety Agency that brings together innovators to collaborate, share and learn. These and many others were presented at the Transport and Infrastructure 2018 seminar this autumn.

In turn, the public sector ambitions to incorporate digitalization and servitization into the transport sector were recently highlighted in the scenarios for carbon-free transport by 2045. From the follow-up work on these scenarios, we expect to see concrete action plans that embrace the full business and societal potential of platform innovations.

Selected articles and websites

Anne Berner, Minister of Transport and Communications of Finland: Alustatalous liikuttaa myös Suomea, Impulssi-blogi

Anne Berner, Minister of Transport and Communications of Finland: Opening markets in the digital era, New Europe

Carbon-free transport by 2045 – Paths to an emission-free future. Interim report by the Transport Climate Policy working group

Heikki Metsäranta: Ideologiat liikennepolitiikassa, Tie & Liikenne 4, 2018

The Ministry of Transport and Communications: Act on Transport Services

Traffic Lab website, Finnish Transport Safety Agency

Väylät & Liikenne 2018 esitelmät (Transport and Infrastructure 2018 Seminar proceeding summaries)

Turning common pessimistic beliefs of platforms into positive narratives

In this signal post we tackle four commonly stated beliefs that suggest the platform economy is but a game of global giants and Finland has very little chance to benefit or take part. These critical messages heard over and over again are:

- “We cannot compete with giants.”

- “It is already too late.”

- “Finland is too small.”

- “The US or China is going to take it all.”

While all the above four statements are valid concerns, we will explore them one by one with the aim to extend the discussion from pessimistic caution towards narratives of encouragement. In fact, we’d rather suggest using these statements to challenge practitioners to think of ways to get involved in the value creation networks that indeed are characterised by giant platform companies steering fast-paced developments in a global context. Positive messages have also been emphasised in the national strategy work and ministerial future reviews. Our recommendations for surviving and excelling in this game include the following:

- Join and contribute in an ecosystem.

- Use your unique strengths and find your niche.

- Think digital and global but do not forget about tangible and local.

“We cannot compete with giants”

When looking at the successful platform giants, such as Amazon, Alibaba, Spotify, YouTube, Baidu, Apple, Uber or Airbnb, you may wonder whether there is any room for new entrants. These giants have grown relatively fast and assumed leading or even monopolistic standing in regional and global markets. They are not only dominating the digitally powered business but often disrupting the traditional trade and industries too.

The point is, however, not to pick a fight and compete with one of these forerunner giants enjoying their monopoly position. Although you could do that too, if you come up with a more efficient, attractive or innovative service than what they offer. In fact, the monopoly status of many of these platforms could start to crumble as soon as strong new competitors with fresh ideas get their act together. An alternative newcomer strategy would be to explore interconnected business openings complementary to those of the giants. After all, the platform economy is the perfect environment to make use of business models based on multi-stakeholder value networks and ecosystems, layered services and synergetic alliances.

One should also acknowledge the longer-term fluctuations in economic success. Even giants fall, and monopolies may need to make room for a more diverse market situation. Social media platforms are a good example of an “industry”, where we have already seen pioneers and former market leaders such as MySpace and IRC-Galleria to lose their standing to a multitude of new, specialised platforms for private, professional and other purposes.

“It is already too late”

Again, if focusing on the incumbent giants, one might think it’s all been done already, and that it is too late to start from scratch. But the fact is that many business sectors are only beginning to warm up to the idea of the platform economy. Futures enabled by digitalisation remain in many business areas just visionary talk, as companies and other practitioners still rely on traditional business models, pipe-like supply chains and one-sided market logics. Innovative thinking and openness to apply the principles of the platform economy will provide countless new business opportunities in sectors like real estate, construction, waste management, manufacturing and agriculture.

New opportunities are also to be discovered with applying emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence, blockchain, robotics and virtual reality. It is definitely not too late to contribute to the development of these technologies and the yet undiscovered potential they have when applied into digital platforms. New services, business models and delivery channels in sight!

“Finland is too small”

As a small, remote country it is easy to think we cannot make a big difference in the global game. Our domestic market is not big enough and we are but a population of some five million. The platform economy, however, is the perfect arena for even a small actor to grow and achieve international success. The European Single Market is our extended home ground, and there are no barriers that couldn’t be overcome in terms of global growth either. And again, platform strategies are all about alliances and partnerships, and the Finnish can surely find their niche as a part of these platform ecosystems.

The high level of education, expertise and skills in Finland is an important asset in the platform economy. ICT skills, databanks as well as knowledgeable citizens are a key resource in developing platforms as well as in introducing them in the consumer market. The compact domestic market can also be taken as an advantage, if used as a test-bed and proof-of-case to explore and market forerunner services. Well-connected stakeholder ecosystems can collaborate on domestic applications and then expand internationally, as we have seen with the example of mobility as a service business.

“The US or China is going to take it all”

The US and Chinese platform ecosystems are undoubtedly dominating the platform business for now, and for the time being Europe is largely dependent on the US-driven ecosystem. Finland and Europe among other countries and regions can nevertheless contribute to the development of these agglomerates. For example, it has been suggested that European public values could be employed to bring important value-centric platform policies into the big picture. The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is already one major step forward, and besides privacy, values such as accountability, fairness and democratic control could be similarly promoted. The European strength in the traditional markets to balance power relationships and support stakeholder collaboration among (1) the market, (2) state and (3) civil society makes a strong case in the platform economy too. It could indeed provide a more acceptable alternative to the current focus of the US ecosystem on the market or that of the Chinese ecosystem on the state.

Another counter-argument to the dominance of the US, China or any other superpower is that even if the platform economy strives on digital solutions on the global level, many practical applications have roots in the tangible, physical world too. These types of local aspects are manifested in e.g. services and products being produced and consumed, which means business opportunities can be found both near and far.

Selected articles and websites

Valtioneuvoston kanslia, Työ- ja elinkeinoministeriö, Innovaatiorahoituskeskus Tekes: Digitaalisen alustatalouden tiekartasto

Finnish Government, Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment: From transformation to new growth, Futures Review of the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment

Ailisto, et al. 2016: Onko Suomi jäämässä alustatalouden junasta? Valtioneuvoston selvitys- ja tutkimustoiminnan julkaisusarja 19/2016

van Dijck (2018): European public values in a global online society, Keynote at the workshop: “Platform Economy: Innovation, Entrepreneurship and Public Policy Perspectives”

Food in the platform economy: Consumer apps, production chain management and visionary ideas

This signal post provides an overview of progress and expected future directions of digital platforms in the context of food. Firstly, we take a look at existing platforms of different type within the consumer interface. Secondly, we explore the wider opportunities of platforms along entire food production chains and ecosystems. Thirdly, we identify a handful of emerging platform innovations waiting to enter the markets.

Platforms for the consumer

In the context of food, digital platforms for consumers can make the daily life more convenient, efficient and affordable. Comparing choices is easier, payments happen online and deliveries can be arranged too. Special deals and personalised offers are being increasingly used, and customer review systems act as an in-built quality control measure. Digital platforms may also serve as gateways to widen the range of accessible choices for consumers or bring additional benefits such as social connections. A platform can help arrange a lunch date with a potential new business partner or connect like-minded people to cook and eat a meal together.

Platforms for everyday grocery shopping remain for the time being primarily company-specific initiatives, as large grocery retailers that dominate the traditional markets have preferred to build their own platforms rather than common marketplaces. The restaurant business, specialised small-scale producers and consumer-to-consumer segments have, on the contrary, been keen to adopt platforms based on two-sided or multi-sided markets. Examples of these include:

- platforms for finding, booking, paying and reviewing restaurants, e.g. Eat.fi (Finland + international) and Foursquare (USA + international)

- platforms for ordering and paying takeaway food or food deliveries from restaurants, e.g. Pizza-online (Finland), Wolt (Finland + international) Foodora (Germany + international) and Uber Eats (USA + international)

- platforms for buying and paying for food and groceries directly from typically small or local producers, e.g. Farmhouse (Australia), OurHarvest (USA), Maano (Zambia) and Forestfoody (Finland)

- platforms for buying and paying affordable surplus meal deals or food products from restaurants or grocery wholesalers, e.g. ResQ (Finland + international) and Fiksuruoka.fi (Finland)

- platforms in the consumer-to-consumer space such as meal sharing, pop up activities, food swap, etc., e.g. Ravintolapäivä (Finland + international), Meal Sharing, foodsharing (Germany) and Traveling Spoon.

It is notable that many of the established and emerging platforms contribute to (economically, environmentally or socially) sustainable consumption patterns and sharing economy principles. Restaurants and households alike are minimising food waste, and social connections and community spirit are fostered through local activities. Even the food delivery services are, instead of simply increasing motorised transport and related negative externalities, growingly using sustainable alternatives like bike couriers.

Platforms for the food production chain

Digital platforms have potential also in capturing entire supply chains and supply network ecosystems of food production. The food industry is, in fact, an exceptionally interesting application area, because benefits of digitally managed production chains do not limit to the obvious efficiency savings but extend to topics such as food safety, cold chain management and transparency in production conditions and origin.

One example of future opportunities with digitalisation is the so called Food Economy 4.0 that paints a picture of a sustainable consumer-centric ecosystem. The core of this concept relies on three change paths: (1) from mass production to personalised solutions, (2) from centralisation to agile manufacturing and delivery and (3) from horizontal to vertical food production. In Finland, a strategic roadmap has even been drafted to an envisioned consumer data-driven, digital platform model to disrupt inflexible and inefficient value chain structures among primary production, various industry sectors, logistics, retail and service sectors in the food chain. This concept foresees that industrial platform creation could proceed step-wisely and ultimately evolve from transportation, warehousing and market platforms into long-term interoperability across industries and platforms.

Similar ideas relating to the currently linear, industrialised and centralised food supply chains are also promoted in examples such as food hubs, precision agriculture and analytics, recycling applications and dietary information systems. Even if we currently see these concepts emerging as standalone applications and platforms, the next step forward would be to embed and interconnect them throughout value networks. Stakeholder collaboration and novel thinking will be a necessity, but synergetic effects and added value are expected to be substantial.

Longer term visions

Even more innovative long-term visions for food in the platform economy include initiatives that plan to use blockchain technologies to manage transactions. Russian-originated INS Ecosystem plans to transform the push-based grocery business to a pull, using a dynamic system to fulfil orders and adjust prices by connecting sellers and buyers directly. This efficiency improvement would minimise the need for shelving foods and also reduce waste. Another similar decentralised marketplace initiative is BlockFood with its technical architecture based on smart contracts that allow customers to order food from restaurants and have it delivered. A third example, FoodCoin, has perhaps even more ambitious plans, aiming to create a global marketplace of food and agricultural products using the Ethereum technology. The platform would engage all actors along the supply chain from farmers and equipment manufacturers to food manufacturers, restaurants and consumers. All of these platforms have advanced plans to make use of tokens and cryptocurrencies.

But what if the food itself that we consume will change dramatically? Powdered meals and personalised food fabrication are examples of such innovations. These would implicate even wider opportunities for digital platforms, as instead of traditional recipes and supply chains the demand would expand to smart, personalised diet planning and novel nutrient markets. The focus could thus move from platforms optimising logistics to platforms providing intelligent nutritional solutions that are tailored to personal needs. Further on, personalised approach to food to improve wellbeing and health could even be combined with measuring and monitoring of your daily condition, genetic information and personal goals. And all of this could be interlinked to platforms that use nudging and positive reinforcement to encourage positive behavioural patterns in our daily choices, a step forward from what platforms like Zipongo are already exploring.

Selected articles and websites

Allfoodexperts: Food powder. Eat what you like

Allfoodexperts: Sharing Economy Reaches Food: Startups Based on Collaborative Networks

BlockFood: BlockFood is the world’s first decentralized food ordering & delivery platform

Complexity Labs: Food Systems Innovation

FoodCoin Ecosystem: Global blockchain ecosystem for food and agriculture businesses

GreenBiz, RP Siegel: This blockchain startup is hungry to address the grocery industry’s food waste dilemma

INS Ecosystem: A Decentralized Online Grocery Marketplace: How it Works for Consumers

Kotiranta et al. (2017): Roadmap for Renewal: A Shared Platform in the Food Industry

MedTech Engine, Mariëtte Abrahams: The personalised nutrition trend – how digital health brands can revolutionise healthcare

News.com.au, Frank Chung: CSIRO sets sights on personalised ‘food generator’ based on your DNA, lifestyle and even sweat

Platform Value Now, Heidi Auvinen: Digital platforms for supply chains and logistics

Poutanen et al. (2017): Food economy 4.0 VTT’s vision towards intelligent, consumer-centric food production

The Technology Media, Elina Koskipahta: The platform combines feedback from journalists, food critics and local users

World Food Program: Maano – Virtual Farmers Market

Zipongo: Eating well made simple

Profiling of users in online platforms

This signal post drills into the topic of profiling of platform users. We will have a look at how information on users’ background together with data on their offline and online behaviour is used by platforms and allied businesses. On the one hand, profiling allows service providers to answer user needs and to tailor personalised content. On the other hand, being constantly surveyed and analysed can become too much, especially when exhaustive profiling efforts across platforms begin to limit or even control individuals based on evaluations, groupings and ratings. The ever increasing use of smart phones and apps, as well as use of artificial intelligence and other enabling technologies, are in particular accelerating the business around profiling, and individuals as well as regulators may find themselves somewhat puzzled in this game.

What is profiling all about?

In the context of the platform economy, we understand profiling as collecting, analysis and application of user data as a part of the functioning of a platform. This means that e.g. algorithms are used to access and process vast amounts of data, such as personal background information and records of online behaviour. The level of digital profiling can vary greatly, and a simple example would contain a user profile created by an individual and their record of activities within one platform. A more complex case could be a multi-platform user ID that not only records all of the user’s actions on several platforms but also makes use of externally acquired data, such as data on credit card usage.

The core purpose of profiling is for the platforms to simply better understand their customers and develop their services. User profiles for individuals or groups allow targeting and personalisation of the offering based on user needs and preferences, and practical examples of making use of this knowledge include tailoring of services, price-discrimination, fraud detection and filtering of either services or users.

Pros and cons of profiling

From the user perspective, profiling is often discussed regarding problems that arise. Firstly, the data collected is largely from sources other than the individuals themselves, and the whole process of information gathering and processing is often a non-transparent activity. The user may thus have little or no knowledge of what is being known and recorded of them or how their user profile data is analysed. Secondly, how profiles are made use of in platforms, as well as how this data may be redistributed and sold onwards, is a concern. Discrimination may apply not only to needs-based tailoring of service offering and pricing but extend into ethically questionable decisions based on income, ethnicity, religion, age, location, the circle of friends, gender, etc. It should also be acknowledged that profiling may lead to misjudgement and faulty conclusions, and it may be impossible for the user to correct and escape such situations. The third and most serious problem area with profiling is when data and information on users is applied in harmful and malicious ways. This involves, for example, intentionally narrowing down options and exposure of the user to information or services or aggressively manipulating, shaping and influencing user behaviour. In practice this can mean filter bubbles, fake news, exclusion, political propaganda, etc. And in fact, the very idea of everything we do online or offline being recorded and corporations and governments being able to access this information can be pretty intimidating. Let alone the risk of this information being hacked and used for criminal purposes. Add advanced data analytics and artificial intelligence to the equation and the threats seem even less manageable.

However, profiling can and should rather be a virtuous cycle that allows platforms to create more relevant services and tailor personalised, or even hyper-personalised, content. This means a smooth “customer journey” with easy and timely access to whatever it is that an individual finds interesting or is in need of. Profiling may help you find compatible or interlinked products, reward you with personally tailored offers and for example allow services and pricing to be adjusted fairly to your lifestyle. In the future we’re also expecting behavioural analytics and psychological profiling to be used increasingly in anticipatory functions, for example to detect security, health or wellbeing deviations. These new application areas can be important not only for the individual but the society as a whole. Imagine fraud, terrorism or suicidal behaviours being tactfully addressed at early stages of emergence.

Where do we go from here?

Concerns raised over profiling are inducing actions in the public and private sectors respectively and in collaboration. A focal example in the topic of data management in Europe is the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) (EU) 2016/679 that will be applied in all European Union Member States from 25 May 2018 onwards. This regulation addresses the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data. And even if launched as a European rather than a global initiative, the GDPR applies to all entities processing personal data of EU citizens, and many global players have in fact already claimed compliance in all their practices. Issues covered by the regulation include limiting the scope of personal data to be collected, the individual’s right to access data on them and detailed responsibilities for those processing personal data.

While the EU tries to manage the protection of personal data and thus bring transparency and fairness to profiling, the Chinese government is exploring a very different direction by being taking the lead in gradually introducing a Social Credit System. This model is at the moment being piloted, with the aim to establish the ultimate profiling effort of citizens regarding their economic and social status. Examples of the functioning of the credit system include using the data sourced from a multitude of surveillance sources to control citizens’ access to transport, schools, jobs or even dating websites based on their score.

Another type of initiative is the Finnish undertaking to build an alternative system empowering individuals to have an active role in defining the services and conditions under which their personal information is used. The IHAN (International Human Account Network) account system for data exchange, as promoted by the Finnish Innovation Fund Sitra, is designed analogously to the IBAN (International Bank Account Number) system used in banking. The aim with IHAN is to establish an ecosystem for fair human-driven data economy, at first starting in Finland and then extending to Europe and onwards. The plan entails creating common rules and concept for information exchange, and testing of the technical platform will be done together with pilots from areas of health, transport, agriculture, etc.

Selected articles and websites

Business Insider Nordic: China has started ranking citizens with a creepy ‘social credit’ system — here’s what you can do wrong, and the embarrassing, demeaning ways they can punish you

François Chollet: What worries me about AI

General Data Protection Regulation (EU) 2016/679 – EUR-Lex

Kirk Borne: Top Data Trends for 2018 – Part 1

Platform Value Now: Tackling fake news and misinformation in platforms

Sitra: Human-driven data economy

Wikipedia: Profiling (information science)

Wikipedia: Social Credit System

Wolfie Christl, Cracked Labs: Corporate Surveillance in Everyday Life

Tackling fake news and misinformation in platforms

The online world is increasingly struggling with misinformation, such as fake news, that is spreading in digital platforms. Intentionally as well as unintentionally created and spread false content travels fast in platforms and may reach global audiences instantaneously. To pre-screen, monitor, correct or control the spreading is extremely difficult, and often the remedial response comes only in time to deal with the consequences.

In this signal post we study the problem of misinformation in the platform economy but also list potential solutions to it, with forerunner examples. Defining and establishing clear responsibilities through agreements and regulation is one part of the cure, and technological means such as blockchain, reputation systems, algorithms and AI will also be important. Another essential is to support and empower the users to be aware of the issue and practice source criticism, and this can be done for example by embedding critical thinking skills into educational curricula.

Misinformation − the size of the problem

Fake news or misinformation, in general, is not a new phenomenon, but the online world has provided the means to spread it faster and wider with ease. Individuals, organisations and governments alike can be the source or target audience of misinformation, and fake contents can be created and spread with malicious intentions, by accident or even with the objective of entertaining (for example the news satire organization The Onion).

Digital online platforms are often the place where misinformation is being released and then spread by liking, sharing, information searching, bots, etc. The online environment has not yet been able to adopt means to efficiently battle misinformation, and risks and concerns involved vary from reputation damage to global political crises. The most pessimistic views even warn us of an “infocalypse”, a reality-distorting information apocalypse. Others talk about the erosion of civility as a “negative externality”. This view points out that misinformation could, in fact, be tackled by companies in the platform economy analogously to how negative environmental externalities are tackled by manufacturing companies. It has also been suggested that misinformation is a symptom of deep-rooted systemic problems in our information ecosystem and that such an endemic condition in this complex context cannot be very easily fixed.

Solutions − truth, trust and transparency

Remedies to fake news and misinformation are being developed and implemented, even if designing control and repair measures may seem like a mission impossible. Fake accounts and materials are being removed by social media platforms, and efforts to update traditional journalism values and practices in the platform economy are being initiated. Identification and verification processes are a promising opportunity to improve trust, and blockchain among other technologies may prove pivotal in their implementation.

Example: The Council for Mass Media in Finland has recently launched a label for responsible journalism, which is intended to help the user to distinguish fake content and commercials from responsible and trustworthy journalism. The label is meant for both online and traditional media that comply with the guidelines for journalists as provided by the council.

Algorithms and technical design in general will also have an important part to play in ensuring that platforms provide the foundation and structure that repels misinformation. Taking on these responsibilities also calls for rethinking business models and strategies, as demand for transparency grows. One specific issue is the “filter bubble”, a situation where algorithms selectively isolate users to information that revolves around their viewpoint and block off differing information. Platforms such as Facebook are already adjusting and improving their algorithms and practices regarding, for example, their models for advertising.

Example: Digital media company BuzzFeed has launched an “outside your bubble” feature, which specifically gives the reader suggestions of articles providing differing perspectives compared to the piece of news they just read.

Example: YouTube is planning to address misinformation, specifically by adding “information cues” with links to third party sources when it comes to videos covering hoaxes and conspiracy theories. This way the user will automatically have suggestions to access further and possibly differing information on the topic.

Selected articles and websites

BuzzFeed: He Predicted The 2016 Fake News Crisis. Now He’s Worried About An Information Apocalypse.

BuzzFeed: Helping You See Outside Your Bubble

Engadget: Wikipedia had no idea it would become a YouTube fact checker

Financial Times: The tech effect, Every reason to think that social media users will become less engaged with the largest platforms

Julkisen sanan neuvosto: Mistä tiedät, että uutinen on totta?

London School of Economics and Political Science: Dealing with the disinformation dilemma: a new agenda for news media

Science: The science of fake news

The Conversation: Social media companies should ditch clickbait, and compete over trustworthiness

The Onion: About The Onion

Wikipedia: Fake news

Wikipedia: Filter bubble

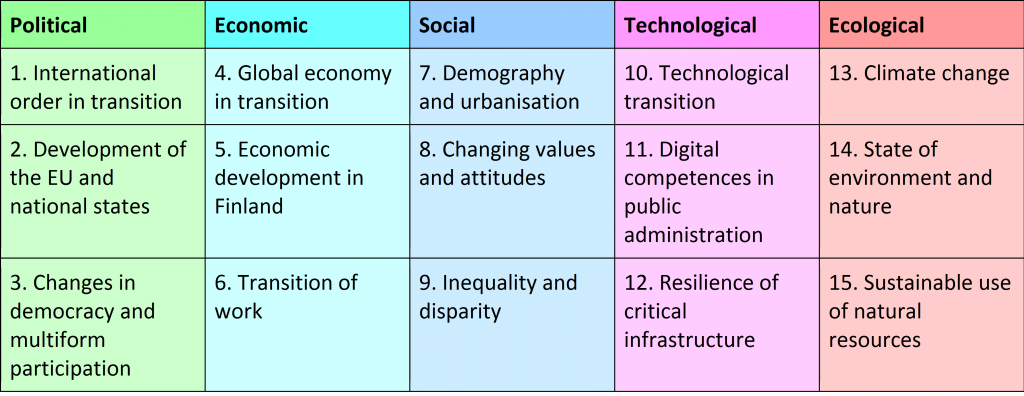

Interpreting the platform economy against landscape-level change factors

The Prime Minister’s Office in Finland published in late 2017 a list of change factors of the global landscape, with the aim to familiarise decision-makers as well as citizens with the changes and uncertainties we will face in the future. The result of fifteen key factors of change was produced in collaboration with experts across ministries and their strategy work. They also provide the basis for dedicated futures outlooks by various ministries to be published later in 2018.

The fifteen change factors each introduce the identified change and describe the situation until 2030. Additionally, alternative paths and development directions are offered. Rather than predictions, the change factors help prepare for various alternatives around the identified change topics, all the while acknowledging uncertainties.

In this signal post, the fifteen change factors are briefly analysed in the context of the platform economy. The idea was to formulate statements as questions and portray the alternative ways the change factor may be expressed in the platform economy. Some of the change factors can act as high level trends that steer platform development from afar, whereas others have very straightforward impact mechanisms. On the other hand, platforms themselves can influence the change factors and contribute to how the changes take place. The objective of this analysis is to help to map the potential with the platform economy regarding both opportunities and threats in the changing societal landscape. In fact, as the platform economy evolves, any of the issues identified may take a positive or negative turn or a combination of the two.

Political

- International order in transition

- Will the USA host as the basis for leading platform companies?

- Can China and the rest of Asia challenge the US leadership?

- Will platforms act as enabling tools in international policy-making?

- Will platforms be used as enabling tools for conflicts and corruption?

- Development of the EU and national states

- Will the EU develop into a competitive and uniformly close-knit platform economy?

- Could we face a failure of joint EU activities in the platform economy?

- Are there going to be nationally or regionally confined platform economies?

- Changes in democracy and multiform participation

- Will platforms act as enablers of accessible knowledge and the information society?

- Will platforms be used to spread polarisation and misinformation?

- Will platforms be employed as tools to societal participation in democracy?

Economic

- Global economy in transition

- Are we going to see globally reigning platform monopolies or local platform economies?

- Is the economic growth from platforms around the world going to be even or uneven?

- Will platforms support quick profits or sustainable growth?

- Economic development in Finland

- Will Finland succeed as a balanced platform economy on its own?

- Is Finland going to excel in its niche areas in the global platform economy?

- Will Finland remain a minor actor in the platform business?

- Transition of work

- Is all work going to be gig work on platforms?

- Could education, training and skills be provided on platforms on an on-demand basis?

Social

- Demography and urbanisation

- Can platforms bring along a counter-trend to urbanisation and migration?

- Could platforms help to solve challenges related to ageing?

- Will platforms be used as connectors between culturally or demographically differing groups?

- Changing values and attitudes

- How will ethics and values be incorporated into platforms?

- Could different platforms support variability in choices on lifestyles and values?

- Will platforms be used as a destructive force?

- Inequality and disparity

- Will platforms be employed to empower women and build equal opportunities globally?

- Will platforms be used to aggravate polarisation of individuals and nations?

- Can platforms contribute to accessible human health and wellbeing?

Technological

- Technological transition

- Will blockchain, AI, robots, etc. be employed successfully in platforms?

- Is the role of platforms and advanced technologies to be in control or as a subordinate?

- Could we face technological underachievement and failure of the platform economy?

- Will data be the currency of the future technological platforms?

- Digital competences in public administration

- Will the public sector be active in platform management and participation?

- Is public administration going to be incapable of deploying digital platforms in their own processes?

- Can the public sector keep up with platform markets?

- Resilience of critical infrastructure

- Will platforms bring intelligence into infrastructure management?

- Will we be able to ensure resilience regarding digital infrastructures and cyber security?

Ecological

- Climate change

- Could platforms and advanced technologies contribute to effective agreements in climate policy?

- Will digital platforms increase or decrease the overall environmental burden?

- Could the platform economy provide the means to survive with climate change impacts?

- State of environment and nature

- Could platforms facilitate monitoring of natural and built environments?

- Sustainable use of natural resources

- Could platforms be used as enabling tools for material and resource management, e.g. recycling?

- Will sharing platforms promote effectively sustainable, resource-efficient lifestyles and economies?

- Will unsustainable consumption patterns spread uncontrollably because of platforms?

- Are platforms, data and related technologies going to increase energy consumption exceedingly?

Selected articles and websites

Ethics in the platform economy

Technology development has reached the phase where technology provides direct actions and services without the need of a human being involvement. In platforms, data is the asset and multiple technologies are used to collect, store, analyse, share and present the data. AI makes analyses, diagnoses and decisions, robots perform human like actions and mobile phones offer everybody an access to the integrated systems (platforms) formed by the new and emerging technologies. The novel systems are not only showcases any longer but they are an essential part of our everyday life. Therefore, ethics plays an important role in these complex systems and needs to be studied carefully.

In this signal post we discuss the ethical challenges of platforms and the applied technologies and explore the possibilities to take ethics into account when designing and developing new systems.

Ethics and emerging technologies

Ethics refers to “moral principles that govern a person’s behaviour or the conducting of an activity”, “the moral correctness of specified conduct” or “the branch of knowledge that deals with moral principles”. The minimum set of ethical and moral principles are implemented in laws and regulations, which often are trailing behind the technology development. One example of such a situation is the collection and use of data: the big platform players have collected personal data for years and used it in building their systems and services. Now the EU is launching the General Data Protection Regulation (Directive 95/46/EC) which will be in force on 25 May 2018. Another area of current ethical concerns is the autonomous vehicles, both for civil and military purposes. In case of autonomous cars, how should the optimization be made, whom or what (human welfare, safety of the passenger or those on the road, environment, etc.) to prioritize and on what grounds?

On the other hand, ethical challenges in the medical and pharmaceutical R&D have been identified in time and the regulations and codes of conducts were first developed there and are in place in developed countries. However, the emerging technologies constantly trigger new ethical issues. Current ones include the genome editing and the use of robots in taking care of patients or elderly people. The modern health care platforms tend to imply all possible ethical issues from personal data protection to the use of AI and robots in any imaginable combinations.

Ethics assessment

In case of the development and application of emerging technologies, regulation may not always be timely enough and more generic forward looking guidance is needed. The EU SATORI project developed a CEN workshop agreement on ethics assessment and an ethical impact assessment framework for research and innovation. IEEE has introduced a Global Initiative for Ethical Considerations in Artificial Intelligence and Autonomous Systems. Its General Principles Committee seeks to articulate high-level ethical concerns that apply to all types of artificial intelligence and autonomous systems that:

1) “Embody the highest ideals of human rights that honour their inherent dignity and worth.

2) Prioritize the maximum benefit to humanity and the natural environment.

3) Mitigate risks and negative impacts as AI/AS evolve as socio-technical systems.”

In an ideal world, the ethical principles should be harmonized to avoid the “distant working” in such countries where the regulation allows the unethical actions. The harmonization is challenging because the interpretation of ethics is based on moral principles and those vary from culture to culture. Discussion and collaboration between technology developers, philosophers and sociologists are needed to develop the principles and necessary codes of conducts. The transparency offered by social media platforms can be helpful in raising the awareness of ethics. When taking the issue further, the prevailing culture should be built into the systems if we don’t want the systems to develop our culture in the future.

Selected articles and websites

Directive 95/46/EC, The General Data Protection Regulation

Ethics assessment for research and innovation – Part 1: Ethics committee

Ethics assessment for research and innovation – Part 2: Ethical impact assessment framework

Finland Banks on Medical Robots to Facilitate Elderly Care

SATORI- Stakeholders Acting Together On the ethical impact assessment of Research and Innovation

Shashkevich, A., Stanford scholars, researchers discuss key ethical questions self-driving cars present

The IEEE Global Initiative on Ethics of Autonomous and Intelligent Systems

What are genome editing and CRISPR-Cas9?

Platforms for education and learning

A digital platform is in many ways the ideal tool to manage inflow, storage and outflow of knowledge. Data, information, news, knowledge and other types of content can be produced and collected on a platform. A platform also serves as a mediator and broker of these contents, providing access and enabling algorithmic or collaborative means to process it. Furthermore, a platform provides an interface for absorbing knowledge, i.e. to learn, study and be informed.

In this signal post we will have a look at some examples of platform economy entering the world of education and learning. The two topics under analysis are: (1) e-learning platforms in formal education and (2) online education resources and degrees.

E-learning platforms in formal education

Online platforms have been adopted in formal education on levels. Schools and universities manage their curriculum, learning materials, assignments, distance education, etc. in platforms. These e-learning platforms help the educational establishments and teachers to organise their work as well as the students to organise theirs. In a way, you could think of the platform being the teachers’ room, classroom and personal study space in one. Online environment additionally facilitates collaboration, for example between students in projects or between teachers, students and parents. E-learning platforms have replaced some of the previously ‘manual’ functions, but they have also provided completely new opportunities. In the big picture, they do nevertheless support and complement traditional classroom-type formal education rather than fully replace it.

One of the best known e-learning platforms is Moodle. It belongs to the tradition of open source software, and it is popular all over the world. The key traits of the system include the opportunity to scale, adapt and modify it and the flexibility to create personalised learning environments under one umbrella.

Online education resources and degrees

Another type of application of the platform economy is the fully online education and learning platforms such as Khan Academy (free online learning resource) and Udacity (free online classes and commercial nanodegrees). Suchlike platforms can provide programs similar to those by formal educational institutions or smaller study entities for vocational or personal learning. Online education resources and degrees are typically open for all, enabling worldwide attendance, and targeting mainly adults. Some function as free non-profit initiatives while others are run as profitable businesses, much like open universities and municipal or commercial education centres.

For example, Khan Academy provides a free, no-ad online education platform that partners with respected institutions such as NASA and MIT. The offering stretches from kindergarten level to science and programming. Udacity, on the other hand, has developed a so-called online nanodegree program product, where industry leaders and expert instructors offer a personalised learning experience. These intensive programs of 6-12 months even guarantee the graduates to land a job within six months of graduation or their tuition is refunded.

Things to keep an eye on

While the platform economy is employing digitalisation to make education and learning more efficient and accessible, there are also factors of uncertainty and risk. One question of uncertainty is what will be the future balance of formal and informal education. New types of education platforms may in fact have a significant role as the timely provider of new skills and competences required at different career stages. Another issue is the risks involved in the online environment, where it is difficult to verify quality or address ethical and cultural aspects of the vast flow of new information and new services.

Regarding advanced technologies linked to the platform economy, such as blockchain and artificial intelligence (AI), the education sector among others is likely to be affected. For example, the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre’s (JRC) recently published a study on blockchain in education, and the report describes promising opportunities to involve blockchain technologies in student information systems and granting or verifying certificates, etc. And according to cloud platform company Tokbox, AI may further transform the education experience by bringing along for example smart content, intelligent tutoring systems, 3D environments and universal online learning.

Selected articles and websites

Grech, A. and Camilleri, A. F. (2017). Blockchain in Education. Inamorato dos Santos, A. (ed.)

Liu, H. Men and J. Han (2009). Comparative Study of Open-Source E-Learning Management Platform. 2009 International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Software Engineering, Wuhan, pp. 1-4

Khan Academy: A personalized learning resource for all ages

Moodle: Moodle learning platform

TokBox: The Edge of Automation: Artificial Intelligence in Education

Udacity: Free online classes and Nanodegrees