This time we have a guest author, who provides a fresh and personal view into the platform economy. Akseli spent two weeks at VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland Ltd in November 2017, completing his work practice programme. One of the tasks Akseli took on was to familiarize himself with the concept of the platform economy and write his very own signal post on a topic of his choice.

Akseli chose to look into Youtube gaming, and how gaming companies, gamers and regulators are currently in a difficult situation. Many interesting things are happening in this area, but the rules of the game are not always so clear…

Hi! I’m Akseli Ala-Juusela, I’m 15 years old, and I was instructed to write a blog post on platform economy, so here we are!

Many people around the world take advantage of platforms like Uber, AirBnB and Youtube. Some problems have emerged, though, as huge corporations are looking for their share in advertisements and profits from the platform.

Challenges of Youtube gaming

I’m going to use Youtube as an example since I’m most aware of its issues. You see there are underlying problems for anybody trying to play videogames for an online audience. The entertainers need to have written permission from the maker according to some, and just purchasing the game and commenting on what is happening on the screen is enough according to others. There are some clear copyright violations like uploading the whole of Star Wars to Youtube without permission from Lucasarts and Disney. But there are also some borderland cases, for example, playing a game while adding your own jokes and commentary.

This leads to all kinds of law talk that I will never understand without going to a law school. But the gist of it is that one court decision could kill a big business and ruin lives of game based internet entertainers who are one of the biggest things dependent on Youtube. These channels are desperately trying to migrate to other forms of entertainment like vlogs (video blogs) and skits (comedy shorts).

We need worldwide rules

The only smart way of going about it is by defining the rules of the internet that will either affect on a global or a local scale. I would suggest the global version as it is much easier to regulate and harder to bypass. The only problem with global rules is that it is hard to punish those you don’t find or can’t reach.

Youtube also has a unique problem that they will probably never completely solve: there are 300 hours of video added there daily [1] which makes weeding out propaganda and terrorists a lot harder. Some countries like Germany require platforms like Youtube to take illegal content off in 24 hours [2], so it is near impossible to please everybody. More so, Germany threatens with a 5-50 million euro fine for not complying so the answer to them was to make a bot that could identify and eliminate anything that could be considered as inflammatory or illegal.

In conclusion: In my opinion, this is a lackluster way to handle situations, and we need a wider set of internationally recognised rules, that are endorsed, for online platforms.

Selected articles and websites

[1] Fortunelords: 36 Mind Blowing YouTube Facts, Figures and Statistics – 2017

[2] BBC News: Germany votes for 50m euro social media fines

A big thank you to Akseli!

Finland’s master plan for platform economy

A couple of weeks ago (October 2017) the Prime Minister’s Office, Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment and Finnish Funding Agency for Innovation Tekes published the national roadmap for digital platform economy for Finland. The first half of the report paints the present picture of the platform economy as a global phenomenon and Finland’s position in it. The second half drills into the national future aspirations for success and growth and introduces a vision and roadmap for Finland. Furthermore, an atlas of ten sector-specific roadmaps is presented and an action plan to fulfil the vision is outlined.

Top-down meets bottom-up

Finland is a pioneer in launching such a comprehensive national vision, roadmap and implementation plan for digital platform economy. Germany, Japan, Singapore and even the EU have touched upon the topic in their industrial or STI (science, technology and innovation) policies, but not with such focused dedication as Finland. The Finnish strategy is to harness platform economy as an enabling tool that has potential to generate growth for businesses as well as enhance productivity of the entire society. A key element of the vision is to develop national competitive edge out of the platform economy.

But why the choice of national and collective approach, when the leading platforms (from the US) have typically emerged as market-based business innovations? The Finnish initiative seems to embrace the platform economy as a wider phenomenon that covers the potential for value creation and capture not just for companies but for citizens and the state alike. Platform ecosystems therefore extend to all actors in the society, and governmental institutions can step up to take active part. According to the report, the foreseen role of public sector includes for example:

- facilitating society-wide dialogue and aligned national vision

- implementing a competitiveness partnership between public and private sectors

- strengthening the development and business environment for platforms

- developing the knowledge base, resources and tools

- showing example by open public data and platforms launched by the public sector

- other enabling support such as regulative measures.

In short, the Finnish hypothesis for how to accelerate and benefit from the platform economy is to activate both the bottom-up (innovators, businesses, individuals, etc.) and top-down (governments, authorities, regulators, etc.) stakeholders. No getting stuck in the chicken-and-egg dilemma, but getting started on all levels and in a nationwide public-private-partnership.

Other interesting messages

Strengthening of the knowledge base and education to support skills in the platform economy has received a lot of attention in the Finnish roadmap report. This covers both formal education as well as further training along the career path. What is especially highlighted is software design skills, but what about entrepreneurial mindset, data-driven innovativeness and cross-sectoral service thinking?

The value of data and the vast potential for its usage is also emphasized in the report. Data economy as a concept is being mentioned, and especially the role of the public sector is explored in terms of developing rules, providing common technical specifications as well as showing the way with public data resources.

Selected articles and websites

National roadmap report: Digitaalisen alustatalouden tiekartasto

Videos from the launching event (October 23, 2017): Suomi ja tekoäly alustatalouden aikakaudella

Further information: Suomi ja tekoäly alustatalouden aikakaudella

The environmental footprint of the platform economy

The platform economy is inevitably responsible for a myriad of environmental impacts, both positive and negative. These impacts are, however, difficult to identify and measure because of the complex impact chains and rebound effects. Very little research results (especially quantitative) on the topic exists at present moment. In the accompanying video, we list some key factors of the environmental footprint of the platform economy relating to (1) technology, (2) digitalisation and (3) patterns of consumption and production.

Technology

Platforms, as any other digital products and services, rely on large volumes of data centres and computing power. These require considerable amounts of energy, especially in the form of electricity and cooling. On the other hand, in the most hands-on meaning of technology, we need various devices to access platforms. Production of smart phones, tablets, computers, etc. is resource consuming and new models come up constantly. Short-lived, out-dated devices end up as electronic waste.

Digitalisation

Intuitively one might assume that through digitalisation, the platform economy would replace physical and material functions with digital and virtual solutions, and thus diminish use of natural resources and reduce harmful environmental impacts. But in fact, oftentimes platforms have a way of mixing the virtual and physical worlds, in some cases even accelerating material transactions. Secondly, digitalisation enables a global outreach, which in turn can increase global logistics. We have already seen this phenomenon with ever-growing online market places with global user populations.

Consumption and production

Perhaps the most intriguing and crucial factor is the question of consumption and production patterns in the platform economy. It brings us to analyse issues such as societal values, user behaviour, business strategies and political agendas. Will our underlying objective within the platform economy be “more with less”, “more and more” or “less is more”? The topical concepts of the circular economy and sharing economy highlight sustainable and responsible aspirations. In the optimal case the platform economy can align with these concepts and for example implement in practice innovations that promote access instead of ownership.

Selected articles and websites

World Economic Forum: How can digital enable the transition to a more sustainable world?

MRonline: The hidden environmental impacts of “platform capitalism”

Government of the Netherlands, Ministry of Economic Affairs: Argument map The Platform Economy

Bemine, Emma Terämä: Sharing – more common than ever & an integral step on our way to sustainable consumption

Commons, zebras and team economy

The platform economy is much more than business giants Uber, Amazon or Google. Platforms can facilitate a transformation in ways of organising work, value creation, sharing, and resources. While the currently dominant development direction tends to favour large platform companies with monopoly statuses, alternative undercurrents can be identified.

Why is this important?

The focus in the platform economy has largely been on how it enables new ways to create value. Value comes from both users and producers while the platform adds its value to the ecosystem by providing tools for matching and curating the content. Network effects further multiply the value based on the extensiveness of the network.

The sole focus on value creation has, however, lead to ignoring the mechanisms by which value is distributed in the network. Platforms both mediate value creation and add value through connecting actors, sharing resources, and integrating systems, but the question is, how is this value shared? Especially platforms with near monopoly status tend to aggregate much of the value to the platform itself and not share it back to the users of the platforms in a fair amount. Platform companies, like other companies, give the surplus to their shareholders. In some cases, it could even be said that platforms exploit their users by treating them as workforce without benefits or as sources of data to be sold to advertisers. At the same time, little attention is put into how platforms serve society. The discussion is more about how they disrupt existing industries and navigate in the gray areas of legislation.

Three approaches challenging the dominant platform business

Although the big platform companies produce most of the headlines, there are interesting initiatives for alternative forms of platform economy. One is the revitalisation of the idea of commons. In the context of platforms and peer-to-peer economy, commons is understood as a mode of societal organisation, along with market and the state, and combines a resource with a community and a set of protocols. A key question related to platform economy is what data, tools or infrastructure should be treated as commons, how to govern them and how to build both for-profit and non-profit services on top of them. These and other questions of a “commons economy” are being experimented with in peer-to-peer initiatives, platform cooperatives, and blockchain-based distributed autonomous organizations.

In the same way that commons challenges the notion of ownership, a growing number of companies called “Zebras” are challenging the notion of growth. “Zebras” are companies that aim for a sustainable prosperity instead of maximal growth like “Unicorns”. They can still be for-profit but also do social good. An interesting question is whether platform economy can be used to transform the current growth-based economic system towards a more sustainable version, or will the “Zebras” as well as cooperatives and commons be left to the margins in the dominance of platform monopolies.

A third interesting idea utilising the new possibilities of connecting and collaborating through digital platforms is the idea of team economy by GoCo. It challenges the idea of a permanent organisation. In team economy, groups form around an issue or a problem and disperse once the work is done. In contrast to gig economy, the tasks aren’t simplified or clearly defined, but rather what needs to be done is jointly explored with the customer. A platform is needed to connect and offer a collaborative workplace but also provides a record of everything a person has done, a sort of online CV for the platform age.

It remains to be seen to what extent commons, “zebras” and team economy can influence the development of platform economy, but they are interesting ideas to keep an eye on.

Selected articles and websites

- ETUI Policy Brief: The emergence of peer production

- Transnational Institute: Commons Transition and P2P

- Hinesight: Commons or commodities?

- Medium: Zebras Fix What Unicorns Break

- GoCo

Demographic factors in the platform economy: Gender

Often it may feel like we are all anonymous and equal in the online world, but at other times age, gender and other demographic and socio-economic factors seem to matter greatly. In this signal post, we discuss gender in the context of the platform economy. (See also previous post focussing on age.) What is the gender balance among platform users? Who designs and programs platforms? And what is the role of user behaviour and online culture?

Why is this important?

Platform economy has potential to support societal integrity by providing an abundance of opportunities to women and men alike. For example, gig work enabled by digital platforms brings flexibility regarding working hours and location, which is assumed to benefit stay-at home parents, who under other circumstances would stay outside the workforce.

Zooming into platform user populations, in social media usage, Uber passengers and consumers of the on-demand economy there has been found little or no difference in the US in the numbers of women and men. Sounds good! However, if we look at Uber drivers, as much as 86% are male. The exact opposite situation is found with a marketplace for handmade and vintage goods Etsy, where out of the 1.5 million sellers 86% are female. Could it be that platforms reflect and replicate the existing biases and traditions when it comes to the division of labour between women and men?

Another central point of interest is for whom platforms are designed. And who designs them? The inherent male-dominance in the software industry and venture capital is reflected in platforms in that it is dominantly men who design and make decisions about how platforms function. A characteristic example of challenges in this area is the recent controversy over a Google employee manifesto, which shows that despite efforts to increase diversity, old attitudes are very much alive.

An equally important question is how people behave and treat one another when using platforms. A case in point is the numerous incidents of online harassment and doxing (e.g. maliciously gathering and releasing private information about a person). One alarming example from video game culture gone astray is the Gamergate controversy. Online culture also shows in reputation and rating systems, where disclosing of background information such as gender may influence behaviour unfairly.

Things to keep an eye on

For new as well as existing platforms, the topic of gender is an important aspect of consideration in platform design. User strategies can at best pinpoint specific gender-related needs and provide targeted and tailored solutions. Platform owners should also acknowledge the responsibility and equality points of view to ensure the platform welcomes all unique users and treats them on an equal footing. Underlying algorithms as well as the culture of the user population should support equal opportunities and broadmindedness.

Also, it will be increasingly important for governments to keep gender equality in view when promoting digitalisation agendas, especially to involve women. Nations do face different types of challenges based on cultural context and nuances as well as status in financial and technological development, and some recommendations on how to harness women’s potential are given in a recent study.

Selected articles and websites

Harvard Business Review: The On-Demand Economy Is Growing, and Not Just for the Young and Wealthy

Pipes to platforms: How Digital Platforms Increase Inequality

GlobalWebIndex: The Demographics of Uber’s US Users

Uber: The Driver Roadmap

Pew Research Center: Social Media Fact Sheet

Pew Research Center: Online Harassment 2017

Poutanen & Kovalainen (2017): New Economy, Platform Economy and Gender

CNNtech: Storm at Google over engineer’s anti-diversity manifesto

Watanabe et al. (2017): ICT-driven disruptive innovation nurtures un-captured GDP – Harnessing women’s potential as untapped resources

Wikipedia: Gamergate controversy

European Parliament, Think Tank: The Situation of Workers in the Collaborative Economy

openDemocracy: Back to the future: women’s work and the gig economy

Demographic factors in the platform economy: Age

Intuitively thinking online platforms seem to be all about empowerment, hands-on innovation and equal opportunities. In the digital world, anyone can become an entrepreneur, transform ideas into business and, on the other hand, benefit from innovations, products and services provided by others. But how accessible is the platform economy for people of different age? And how evenly are the opportunities and created value distributed? Some fear that platforms are only for the young and enabling the rich get richer while the poor get poorer.

In this signal post, we discuss age in the context of the platform economy. In future postings, we will explore other factors such as gender and educational background.

Why is this important?

When it comes to ICT (Information and Communication Technology) skills and adoption, the young typically are forerunners. For example, social media platforms were in the beginning almost exclusively populated by young adults. But studies show that older generations do follow, and at the moment there is little difference in the percentage of adults in their twenties or thirties using social media in the US. And those in their fifties are not too far behind either!

Along with the megatrend of aging, it makes sense that not only the young but also the middle-aged and above are taking an active part in the platform economy. Some platform companies already acknowledge this, and tailored offering and campaigns to attract older generations have been launched for example in the US. In Australia, the growing number of baby boomers and pre-retirees in the sharing economy platforms, such as online marketplaces and ride-sourcing, has been notable. Explanatory factors include the fact that regulation and transparency around platform business have matured and sense of trust has been boosted.

One peculiar thing to be taken into account is that many platforms actually benefit from attracting diverse user segments, also in terms of age. This shows especially in peer-to-peer sharing platforms. The user population of a platform is typically heavy with millennials, who are less likely to own expensive assets such as cars or real estate. Instead, their values and financial situations favour access to ownership. But the peer-to-peer economy cannot function with only demand, so also supply is needed. It is often the older population that owns the sought-after assets, and they are growingly willing to join sharing platforms. Fascinating statistics are available, for example, of Uber. As much as 65% of Uber users are aged under 35, and less than 10% have passed their 45th birthday. The demographics of Uber drivers tell a different story: adults in their thirties cover no more than 30%, and those aged 40 or more represent half of all drivers. In a nutshell, this means that the older generation provides the service and their offspring uses it.

Things to keep an eye on

In the future, we expect to see more statistics and analysis on user and producer populations of different types of platforms. These will show what demographic segments are attracted by which applications of the platform economy as well as which age groups are possibly missing. The information will help platforms to improve and develop but also address distortion, hindrances and barriers.

It may also be of interest to the public sector to design stronger measures in support of promoting productive and fair participation in the platform economy for people of all ages. Clear and straightforward regulation and other frameworks will be important to build trust and establish common rules.

Selected articles and websites

GlobalWebIndex: The Demographics of Uber’s US Users

Growthology: Millennials and the Platform Economy

Harvard Business Review: The On-Demand Economy Is Growing, and Not Just for the Young and Wealthy

INTHEBLACK: The surprising demographic capitalising on the sharing economy

Pew Research Center: Social Media Fact Sheet

Pipes to platforms: How Digital Platforms Increase Inequality

Uber: The Driver Roadmap

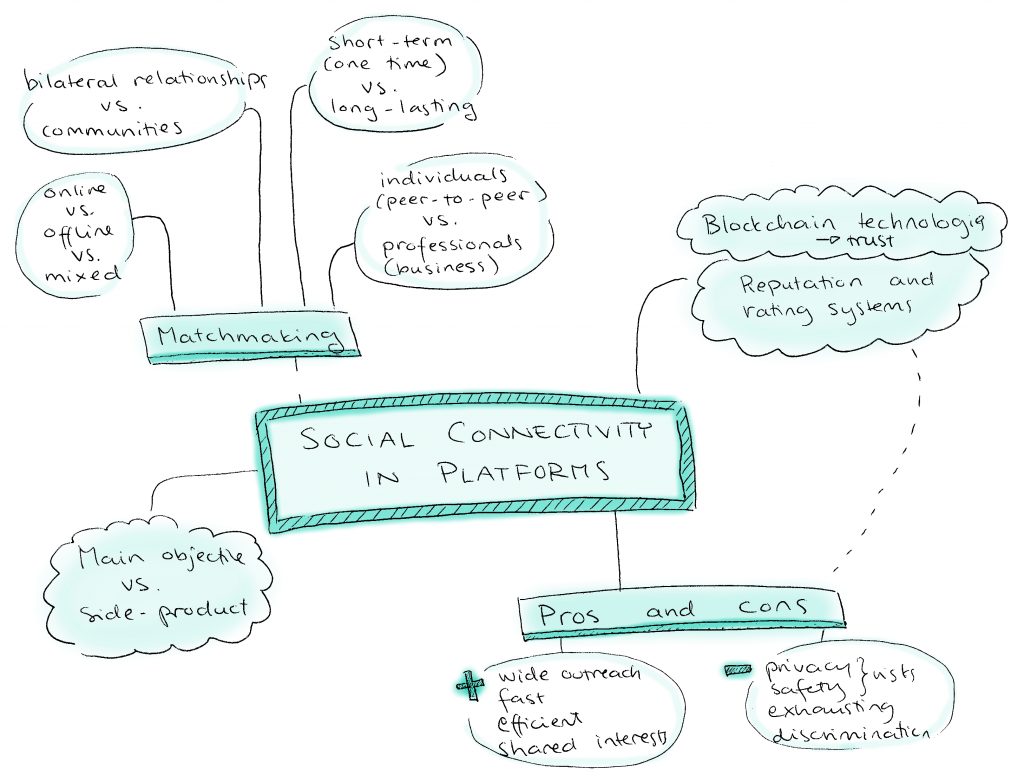

Social connectivity in platforms

Platforms are all about enabling connections to form between actors, typically producers and users of any given tangible or intangible commodity. But to what extent do these connections result in social value for individuals? There are of course social media platforms that by definition focus on maintaining or creating human relationships whether based on family ties, existing friendships, professional networking, dating or shared hobbies or interests. Interaction, communication and social ties nevertheless take place in other platforms too, and the positive and negative impacts of these may come as a rather unexpected side effect to the platform owner as well as users.

For example, ride-sourcing and hospitality platforms are virtual matchmakers, whose work comes to fruition when the virtual connection proceeds to a face-to-face meeting. A ride is then being shared with or a home is being rented to someone who only a little while back was a stranger. Many suchlike relationships remain one-time transactions, but they can also grow to regular exchanges over the platform or profound relationships outside the platform. Connectivity is as much a part of peer-to-peer platforms as professional and work-related platforms. You may form a personal connection with a specific IT specialist over the IT support system platform even if you never met them offline. Or supply chain business partnerships may evolve out of a one-time task brokerage platform transaction.

Why is this important?

The benefits of platform economy regarding social connectivity are the wide outreach and extremely fast and efficient matchmaking based on personal, professional of other mutual interests. In spite of complex technologies and big data flows, these social connections on platforms can be truly personalised, intimate and rewarding. The flipside of the coin is risks around privacy, safety and security. Reputation, review and rating systems are important ways to tackle these and could help to strengthen the sense of trust and community across user populations of platforms. In fact, one interesting finding of social connectivity in platforms is that relationships are maintained and formed bilaterally between the individual as well as among groups, communities and actor ecosystems. Short-term or long-lasting, these relationships often mix online and offline realities.

Additional concerns related to social connectivity in platforms is how much they eventually promote equality and fairness or if the social interaction is more of a burden than a benefit. Reputation and rating systems may result in unfair outcomes, and it may be difficult for entrants to join in a well-established platform community. Prejudices and discrimination exist in online platforms too, and a platform may be prone to conflict if it attracts a very mixed user population. In the ideal case, this works well, e.g. those affluent enough to attain property and purchase expensive vehicles are matched with those needing temporary housing or a ride. But in a more alarming case, a task-brokerage platform may become partial to assigning jobs based on criteria irrelevant to performance, e.g. based on socio-economic background. Platforms can additionally have a stressful impact on individuals if relationships formed are but an exhaustingly numberous short-term consumable.

Emerging technologies linked to platforms are expected to bring a new flavour to social aspects of the online world. The hype around blockchain, for example, holds potential to enhance and ease social connectivity when transactions become more traceable, fair and trustworthy. It has even been claimed that blockchain may be the game changer regarding a social trend to prioritise transparency over anonymity. Blockchain could contribute to individuals and organisations as users becoming increasingly accountable and responsible for any actions they take.

Things to keep an eye on

Besides technology developers and service designers’ efforts to create socially rewarding yet safe platforms, a lot also happens in the public sector. For example, European data protection regulation is being introduced, and the EU policy-making anticipates actions for governance institutions to mobilise in response to the emergence of blockchain technology.

An interesting initiative is also the Chinese authorities’ plan for a centralised, governmental social credit system that would gather data collected from individuals to calculate a credit score that could use in any context such as loans applications or school admissions. By contrast, the US has laws that are specifically aimed to prevent such a system, although similar small-scale endeavours by private companies do to some extent already exist.

Selected articles and websites

Investopedia: What Is a Social Credit Score and How Can it Be Used?

General Data Protection Regulation (EU) 2016/679 – EUR-Lex

European Parliament: What if blockchain changed social values?

European Parliament: How blockchain technology could change our lives

Rahaf Harfoush: Tribes, Flocks, and Single Servings — The Evolution of Digital Behavior

Koen Frenken, Juliet Schor (2017): Putting the sharing economy into perspective, Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions

Paolo Parigi, Bogdan State (2014): Disenchanting the World: The Impact of Technology on Relationships

Social impacts of the platform economy

Platforms create value well beyond economic profits, and the topic of social and societal impacts resulting from the emerging platform economy has been getting more and more attention lately. Platform economy undoubtedly has both positive and negative impacts on individuals and families as well as wider communities and entire societies. However, the range and depth of these impacts can only be speculated, as only very early evidence and research on the topic has been produced. After all, the platform economy is only in its infancy.

Why is this important?

Platforms have potential to address major societal challenges such as those connected to health, transport, demographics, resource efficiency and security. They could massively improve our individual daily lives as well as contribute to equal opportunities and progress in developing economies. On the other hand, platform economy can result in negative impacts in the form of disruptions and new threats. Privacy and safety concerns have deservedly been acknowledged, and other possible risks include those related to social exclusion, discrimination and the ability of policies and regulations to manage with whatever platform economy may bring about.

Some examples of positive and negative social impact categories of the platform economy include the following, which may distribute equally, create further division or bridge the gap among various social segments:

- employment and unemployment

- livelihood and wealth

- education and training

- skills, knowledge and competences

- health and physical wellbeing

- mental health and wellbeing

- privacy, safety and security

- social inclusion or exclusion, access to services, etc.

- new social ties and networks, social mixing

- social interaction and communication: families, communities, etc.

- behaviour and daily routines

- living, accommodation and habitat

- personal identity and empowerment

- equality, equity and equal opportunities or discrimination

- citizen participation, democracy

- sufficiency or lack of political and regulatory frameworks.

Platforms may have very different impacts on different social groups, for example, based on age, gender, religion, ethnicity and nationality. Socioeconomic status, i.e. income, education and occupation, may also play an important role in determining what the impacts are, although it is also possible that platform economy balances out the significance of suchlike factors. One important aspect requiring special attention is how to make sure that vulnerable groups, such as the elderly or those with disabilities or suffering from poverty, can be included to benefit from the platform economy.

Things to keep an eye on

Value captured and created by platforms is at the core of our Platform Value Now (PVN) project, and there are several other on-going research strands addressing social and societal impacts of the platform economy. One key topic will be to analyse and assess impacts of the already established platform companies and initiatives, which necessitates opening the data for research purposes. To better understand the impacts and how they may develop as platform economy matures is of upmost importance to support positive progress and to enable steering, governance and regulatory measures to prevent and mitigate negative impacts.

Selected articles and websites

Koen Frenken, Juliet Schor, Putting the sharing economy into perspective, Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, (2017)

The Rise of the Platform Economy

Uber and the economic impact of sharing economy platforms

VTT Blog: Openness is the key to the platform economy

SUSY project: Solidarity economy

Reputation Economy

Why is this important?

Platform economy often requires trusting strangers. One mechanism for ensuring that everyone plays nicely is to have a reputation system in place. Customers rate the service provider (e.g. Uber driver or Airbnb apartment) and the service provider in turn rates the customer. The ratings or at least their averages are public, which influences who we trust and how we behave in the platform. Reputation is thus a valuable asset in the platform economy.

Things to keep an eye on

Because reputation is valuable, the mechanisms that affect how it is created, shared and used are important. Can the reputation scores be transferred to other services or used in a way not originally intended? Will reputation economy become a new surveillance and control system, as depicted in dystopian images of future, which do not seem so far off given the failed startup Peeple and the Sesame Credit system in place in China.

Selected articles and websites

The Reputation Economy: Are You Ready?

We’ve stopped trusting institutions and started trusting strangers

The reputation economy and its discontents

China has made obedience to the State a game

Black Mirror Is Inspired by a Real-Life Silicon Valley Disaster